TRAUMA: Child survivors of the long-running conflict in the central African country share their experiences – and hopes for a better future.

By John James

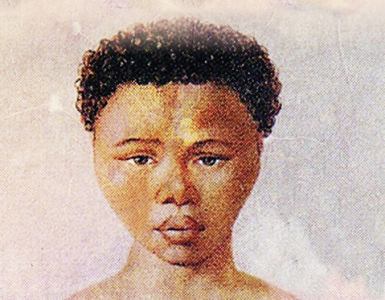

As soon as you meet 17-year-old Francis*, you know his childhood hasn’t been one that anyone deserves. He struggles to make eye contact while we’re talking, and his expression remains mostly blank. When he says he was only six when it all started, I immediately think of my own six-year-old son. It makes it even harder to hear what Francis has been through, things that are almost impossible for a parent to imagine.

Francis says that he was heading to the fields with his father in Ituri Province when they encountered some fighters from a non-state armed group. The fighters forced Francis and his father to come with them to their camp in the forest.

Francis says that he was heading to the fields with his father in Ituri Province when they encountered some fighters from a non-state armed group. The fighters forced Francis and his father to come with them to their camp in the forest.

They told Francis he would have to stay with them while his dad would return home. It was a lie – his father was killed (in a brutal way that I won’t describe here). “You have no-one left, you are staying with us now,’’ someone told him.

From that moment, anything resembling a regular childhood was lost. Instead of going to school, Francis was taught how to fire a gun and use machetes and knives.

“We never stayed in one place, we were always moving,” he says. “I can’t remember how many battles I was in.”

“I couldn’t stop thinking about my dad – I had a lot of anger inside,” he adds. Our conversation took place at a transit and orientation centre in the provincial capital, Bunia. The centre is essentially a place of last resort for children who are difficult to place in a foster family setting. Here they receive counselling for trauma, psychosocial support, medical care and enjoy recreational activities, among other things.

I’m told later by the centre manager, Madeleine Izawa, that Francis rose to the rank of captain in the group he fought in, commanding a group of 70 as a teenager.

“One day, an older member of the group, who was like a brother to me, took me aside and said that this group wasn’t doing good things,” Francis says. “He said we should escape.”

Aged 15 at this point, Francis fled the group. He spent two years in an adult prison, but was eventually identified by the juvenile police and placed into a care centre run by a UNICEF partner. Here he has received psychological treatment, vocational training and medical care.

The years of fighting have already taken a visible toll on Francis’s body – you can see when he stands how years of carrying a heavy machine gun have distorted the way he carries himself. “I regret all the years of missed studies at school,” Francis says.

He’s now in touch with family members in Goma, in the neighbouring province, and hopes to be reunited with them soon. It’s already a lot to take in, but I know I’m here to speak to another child at the centre. Louise* comes in next, wearing a princess dress.

Now 10, she arrived at the centre two weeks ago, but is more comfortable speaking than Francis. I ask her how old she was when she was abducted.

“Eight,” she says, and my heart jumps. My own daughter is eight years old.

Why didn’t these children get the childhood they have a right to? I couldn’t begin to imagine my own children subjected to what Francis and Louise have experienced – abducted by an armed group and spending years in the forest, witnessing unspeakable atrocities.

Louise says she was heading to the capital Kinshasa with her three sisters to see her biological mother, when they were taken by the same non-state armed group.

Louise says she was heading to the capital Kinshasa with her three sisters to see her biological mother, when they were taken by the same non-state armed group.

Two sisters were sent away to other camps in the forest. She was forbidden from spending any time with the other sister, even though she was close by. She was given childcare duties, and the group survived by eating the crops of farmers who had fled the areas they passed through.

Eventually, Louise was able to escape the group, fleeing during a battle. She met other escapees, and when they arrived in Bunia, she was referred to the centre. “I love it here, but I want to return to school and find my family,” she says.

Professional training courses are provided while children wait for family tracing to be completed to help them catch up on schooling and learn a trade. With time, and with the help of social workers and psychologists, the children are able to readjust as they prepare for adulthood.

The children’s stories are marked by horrors, but there are good, kind people, too – people whose lives are dedicated to helping children who may have lost their parents to the conflict and who now await contact with the rest of their families.

As soon as I enter the courtyard of Mama Sophie Makenga, I can sense this is a loving place. The yard is well swept and an oasis of plants and bright colours.

Mama Sophie is a foster mother under the guidance of the Division of Social Affairs. She has spent 14 years taking care of children, sometimes for as long as six months.

“When I take on a child, I share a lot of affection with them, perhaps even more than their other mother gave them,” she says. “It’s complicated at the beginning.”

“I don’t want children to feel institutionalised. I want them to feel this is their home. They get traumatised leaving an armed group, so we engage in dialogue all the time.”

She says children from armed groups have often gone through initiation rituals to force them to dehumanize other people, to make killing easier.

“I really try to understand the child, what toxic experiences they have had,” she says. “Children are like sugar cane. You can uproot them, but if you want to plant them somewhere good, they start growing again in new ground.”

Mama Sophie says that loving children who then move back to their families can be hard. “When they leave, I cry,” she says. “All of us cry.”

But as painful as saying goodbye can be, Mama Sophie knows it means the world for these families to be reunited. Sometimes, because they tell them so themselves.

“I sometimes get a call. One family walked 30 kilometres from their village in the forest to find a phone signal just to call. ‘Thank you, thank you mother’ the family said, and they asked me to send a photo.’’

As I say goodbye to Mama Sophie, I feel that despite the horrors described to me, there are also bright glimmers of hope in the form of these passionate people caring for the country’s children.

I’ll remember them when I go back to see my own children, after a month here in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Children are children the world over, and I’ve been reminded yet again that we must do more to ensure children can enjoy peace with their own families, wherever they are. Sometimes with some extra help, care, and love from people like Mama Sophie.

An upsurge in violence in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) has seen massive new displacement as civilians flee conflict. In 2022, DRC had the world’s highest numbers of UN-verified children who had been recruited or abducted by armed groups. Between January and May 2023, more than 1,200 unaccompanied and separated children were identified, a three-fold increase compared to the same period in 2022.

- Names of the children have been changed. John James is a Communications Specialist for Emergencies in the UNICEF West and Central Africa Regional Office