ICON: A daughter’s mission to protect her late journalist dad’s memory…

By Suzette Mafuna

IN CANADA

Around October 2017, I got an SOS from home to contact Wits University as soon as possible. The university’s representative informed me verbally – following a call from me – of an initiative to award my late dad a Posthumous Honorary Doctorate.

I shared the consent request with my family, completed it, and immediately sent it back. The next request was for my dad’s history – upbringing education and career profile. I dropped everything to find whatever information, records, known contacts, family old and current news items, books, 2nd World War archives and discovered lots more through Google. I remember sitting up overnight to meet the given deadline – there wasn’t much time since the award ceremony had been scheduled for mid-December 2017.

I wasn’t about to let my dad, my family and Wits down by missing the set deadline. The last time I heard from anyone at Wits was when I submitted the final draft citation after scrutinising it for errors – name spelling, accuracy, dates, locations, events etc. Around September I tried reaching out to Wits – emails, private messages.

Nothing.

Many emails later, I was informed that someone else had taken over the project. I read elsewhere that the professor who had headed the Nxumalo project was based at a different university. Around November I was informed that a white spokeswoman had called to confirm a new date – March, 2018, I think.

I remember who called, because they didn’t know that Henry Nxumalo was ‘our brother’, and she was not buying into my request for a limitless number of award invitations for the whole Nxumalo clan. I wanted everybody who had raised my orphaned dad and siblings as their own, nurtured them, sent them to school and did everything to make them feel wanted, cared for, and loved to be part of the celebration.

I wanted those men and women from the sticks of Ezingolweni to turn up at the western-oriented ceremony barefoot, and, in their colourful Zulu regalia – izidwaba, amabheshu, imishiza, amashoba – prancing around in praises of our ancestors our living and departed elders.

This must have scared the hell out of Wits because the flat response was the invitation is limited to 7 guests. The Covid outbreak put paid to my plans – I wasn’t going to have the Nxumalo clan’s imbizo at the prestigious Wits ceremony, after all.

Early this year, I was emailed a screen shot of my dad’s Honorary Doctorate. I could hardly read the faint text and simply shrugged my tired shoulders and let it pass. About a month ago, a friend from home emailed me a copy of the Henry Nxumalo advertisement. I cried. I prayed my rage and my hurt away. It’s taken me a long time to restrain myself from dealing with stuff when I’m angry.

I sat with this thing in my head, in my heart, and in my thoughts for some time. I have been calm, but cold and confused since then. I sent a message for more details about the award and was told to look for it on a Facebook timeline. It seemed everybody else was not expecting to hear from anyone. But I had been sent a print copy of the advertisement.

I had been told I was too radical, was trying to politicise “things”, was interfering, wanted everything to go my way. I have since accepted that, as far as anything to do with the Henry Nxumalo Award, I am a persona non grata, hence my cautious approach in my messages to Wits.

I did not want a confrontation, but I needed to talk to someone about the implications of the brief on my dad’s legacy, his name and reputation and did not like it one bit. I sent a tentative message to a Wits rep hoping to have a discussion about my concerns over the award. I didn’t want to rock the boat; I wouldn’t want anyone to lose their jobs because of me. I opted to write messages to myself ask myself pertinent questions and respond with possible answers still hoping to draw someone’s attention and reaction. My last question dug deep and elicited a swift and haughty response, “I don’t understand your objection. Journalists apply to this fund for their own investigative journalism projects and dozens of projects have come to fruition as a result. There is nothing sinister in calling for applicants who want to investigate the recent violence in KZN and Gauteng. Investigations are expensive and hundreds of journalists have been retrenched and are out of work.

“Even if no one is interested in applying for this by the deadline, it’s still a good thing that people who were not aware of the grant have become aware because of this call and may be motivated to apply for their own project. Further, the award is not already set for specific journalists, white, ageing, of otherwise. How do I know that? Because I was present in the staff meeting when this was suggested and there was agreement that is could be worthwhile for some journalists. And, if there are any applications by Friday. ***will circulate them to the panel that evaluates such applications, of which I am part, and they will be evaluated in exactly the same way as others have been evaluated. What’s your problem, a decision was made. We sat in that meeting. Think about all the unemployed journalists since the covid 19 outbreak. The award is not only for white journalists, anybody can apply and they don’t have to limit themselves to investigating the looting and violence, they are free to investigate something else.”

My response, “so I guess it’s going to be Suzette versus Wits University then.”

My instincts are as sharp as sewing needles, and have not let me down lately. I see things and I know things. I read a lot, I read everything and I read about anything, anyone and everyone. So be assured this gig is mine and mine alone. My body might be lithe, but my shoulders and mind are mighty enough to carry my father’s baggage – his legacy, to wherever and whichever way we land.

Even if this costs Henry Fanyana Nxumalo a Wits Honorary Doctorate, the legacy of his work/life and his National Ikamanga Order – “To award South African citizens who have excelled in the fields of arts, culture, literature, music, journalism and sport.”

They stand us in good stead and don’t cost a dime. I imagine him cracking up, there you go kiddo!tet

*In this last article of a two-part series, Suzette Nxumalo chronicles her battles to preserve her father’s legacy

NOTES ON

HENRY

NXUMALO

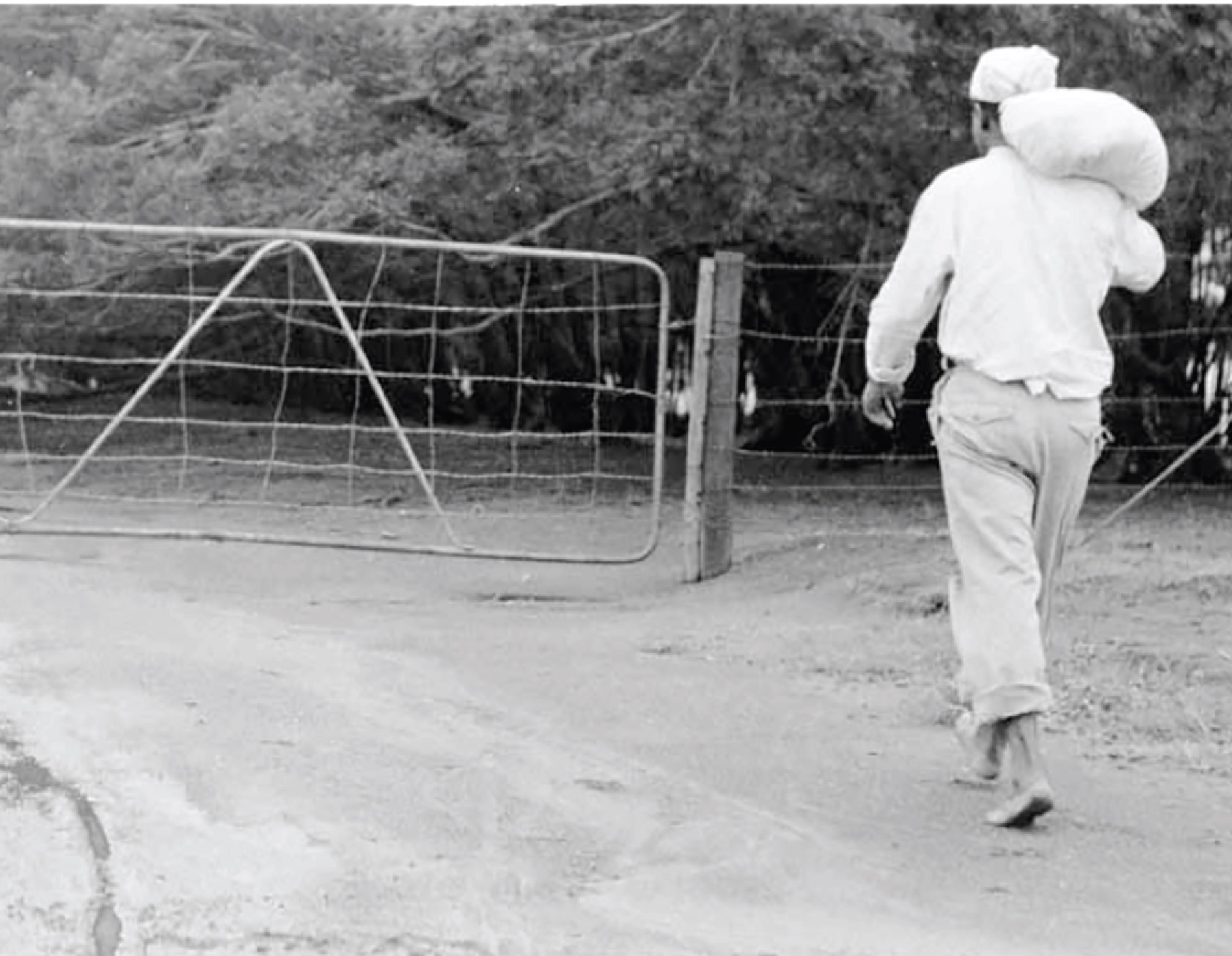

Henry Nxumalo was only in his mid-30s at the time of his murder, said Jurgen Schadeberg, his photographer colleague at Drum magazine at the time.

“There was a doctor who was attached to a police station in the area, and it was known that there had been some botched abortions, some of the patients died. [Henry] tried to investigate it. He went to talk to nurses.” Nxumalo was stabbed while walking home after meeting a colleague for drinks. “We tried to investigate, but police were sloppy about it. They weren’t interested.” (Unfortunately, this is an all too familiar pattern in anti-press violence, where murder represents the ultimate tool of censorship and where authorities lack political will to deliver justice.

The killers of journalists escape justice in nine out of 10 cases, CPJ research shows. CPJ is waging a global campaign to combat this culture of impunity, which breeds a lasting culture of self-censorship for colleagues of the murdered journalist.) In fact, while Nxumalo was survived by a wife and three children, the hard-hitting investigative journalism he pioneered at Drum did not endure, as the magazine gradually did fewer and fewer such stories.

While no one was ever arrested or convicted for Nxumalo’s murder, his colleagues were able to shed some light on the circumstances of his murder. Schadeberg said they were able to track down two criminals whom they believed were hired to carry out the killing. “One of them ended up in prison and he told his story to another prisoner. He said he got 200 pounds [sterling] for it.”

“White Afrikaners were consistently uneasy when Nxumalo introduced himself as a journalist,” Schadeberg said.

“They couldn’t handle it. We interviewed a white official. Henry was asking a question. When he talked to Henry, he used a voice with authority and superiority. If [the official] talks to me, he has a specific type of voice because I’m white. He had to change his voice all the time. He started stuttering!” Schadeberg recalled another occasion, when a policeman he described as a “very young, tough Afrikaner” put a pistol to Schadeberg’s head as he was the first reporter on the scene of a bombing of government buildings by fighters of the African National Congress.

Drum also covered the 1956 high-profile treason trial of 156 anti-apartheid activists including Nelson Mandela. “I photographed Mandela first in 1951, then again in 1952. We used to meet at a printing shop, we had brandy,” Schadeberg said. “Walking into Drum was like leaving South Africa, and coming into a different world,” Schadeberg said of the magazine, adding that its writers came from missionary schools which were mixed and had better education than the segregated schools.

The apartheid government had Drum in its sights. “The Special Branch tried to blackmail some of our people when they went for [their] passport, or permit – they tried to infiltrate the Drum office.” Eventually, Drum went bankrupt in the late 70s-early 80s, and was acquired by the then-pro-National Party newspaper group Naspers, according to Schadeberg.

*This is an excerpt from a report from the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ)