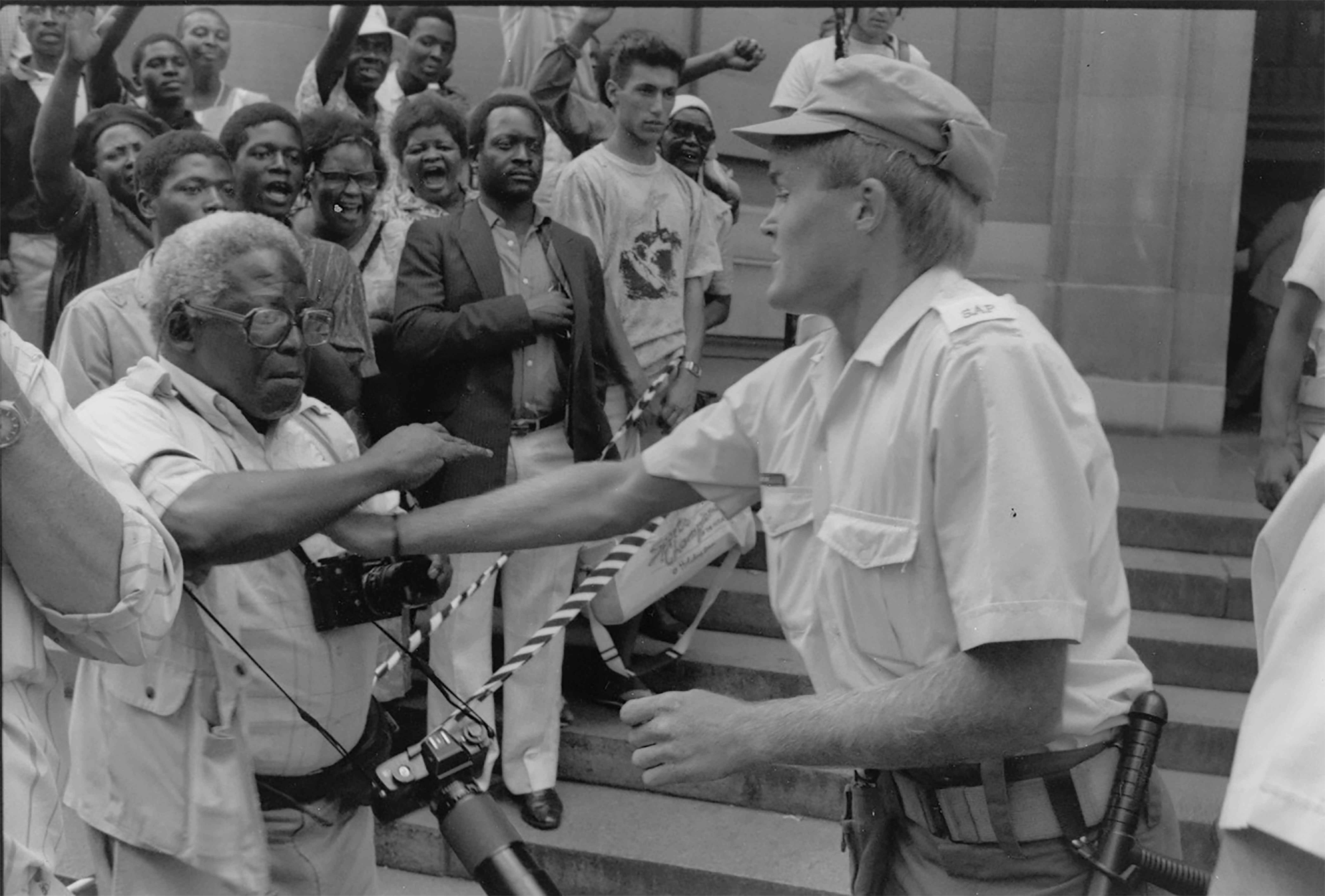

WITNESS: A Struggle without documentation is no Struggle

By Vukani Magubane

Dr Peter Sexford Magubane was born in 1932 in Vrededorp on Johannesburg’s mining belt to Wilhelmina and Isaac Magubane. He grew up in the infamous Sophiatown, a mixed-race suburb in the city of gold.

From the township streets to the hallways of power, Dr Magubane spent more than 60 years behind the lens, capturing everything from social injustice during the apartheid era, political demonstrations, and riots, to the everyday life of women. He also documented the different South African cultures.

Magubane was gifted his first camera, a modest Kodak brownie, by his father when he was a teenager. After completing high school, Magubane was eager to put his camera to use. He found work as a driver at the Drum Magazine offices in 1954. He moved up the ranks to become a darkroom assistant to the late, great photographer Jurgen Schadeberg; a man who would later become Magubane’s friend and mentor.

In 1955, he was given his first assignment as a photographer to cover an annual ANC gathering. It is here that his journey to becoming South Africa’s foremost photojournalist began. During his time at Drum Magazine from 1954 to 1963, Magubane took himself and his camera to the heart of almost every significant historical, political moment during the first wave of anti-apartheid defiance campaigns and the infamous treason trials of the early 1960s.

In 1963, after his tenure at Drum, he travelled to London on freelance work, where he held his first international exhibition at the London School of Printing. A few years later he returned home to Johannesburg and began working at the Rand Daily Mail where he worked until 1980.

His return was marked by political turmoil: from 1967 to 1976, Dr Magubane was repeatedly arrested, detained, interrogated, jailed or placed under house arrest for the work he was engaged in. The apartheid government was besotted with making his life as difficult as possible. In 1969 he was arrested and imprisoned, where he spent 586 consecutive days in solitary confinement—the longest period any prisoner has endured in the country. After this jail time he was served with a banning order of five years which prohibited him from working for any publishing company or publishing any photography.

Magubane was a highly motivated and skillful photographer, a determined storyteller who was preoccupied with getting the image, no matter the obstacles. He came up with many different tricks and methods of getting his images without being detected by the security police. Famously, he would often hide his camera in a hollowed-out loaf of bread, an empty milk carton and even a bible with cutout pages to prevent being detected by the police. Once while documenting the atrocious and inhumane treatment of miners on the mines in Johannesburg he dressed up as a mine foreman, put his camera in his dusk coat pocket and took pictures with a cable release.

Magubane’s photographs bear witness to some of the most defining moments in South African History. He covered the 1955 adoption of the ANC Freedom Charter, the 1950s Sophiatown forced removals, the numerous demonstrations against pass laws, the 1960 Sharpeville Massacre, the Rivonia Treason Trial and many more of the massacres that occurred in the 1960s. He emblazoned into our memory the cruelty of child labour on the white coal and potato farms around the country.

When his banning order was lifted in 1975, Magubane took to the streets to continue his work. He was front and centre during the 1976 Soweto Uprising when the youth took to the streets in protest to the cruel and inhumane Bantu education system. He and other journalists were detained for this. His home was also burnt down by the police in hopes of destroying his film negatives and to deter him from continuing with his work.

In that same year, Magubane was detained by police who broke his nose and terrorised him in efforts to intimidate him. He was hospitalised and true to his character, he was not really upset that his nose had been broken, he was rather distraught that the police had opened his cameras and exposed the film with photographs he had taken that day. He famously said that he knew his nose would heal but he could never ever get those photographs back. Still, he was not discouraged from his work, nor did he have any desire to go into exile. Magubane continued to be on the ground in the turbulent 1980s when South Africa went under several declarations of states of emergency.

In 1985, he was shot 17 times with buckshot and rubber bullets at a student activist’s funeral in Natalspruit. His coverage of the 1976 Soweto uprising and the aftermath that spread throughout South Africa brought him worldwide acclaim and led to several international photographic and journalistic awards, including the American National Professional Photographers Association Humanistic Award in 1986, which also recognised one of the several incidents where he put his camera aside and assisted people from being killed. His 2016 book commemorating the 40th anniversary of the 1976 student uprising is regarded as one of the most important works of a contemporary African to appear in the last two decades.

From 1978 to 1980, Dr. Magubane worked as a correspondent for Time Magazine. He has photographed for several United Nations agencies including the High Commission for Refugees and UNICEF. His photographs appeared in the New York Times, Life Magazine, Time Magazine, Newsweek, National Geographic, Paris Match and the Washington post among others.

He continued to put his life on the line in capturing the bloody political transition of the early 1990s. He was willing and eager when Nelson Mandela asked him to be his personal photographer upon his release in 1991 up until he became president in 1994. Some of President Mandela and his wife and family’s photographs were taken by Magubane—a time during which he became very close to South Africa’s most treasured political figure.

In post-apartheid South Africa, Dr Magubane shifted the focus of his lens to capture and archive imagery of South Africa’s various intricate people and cultures. His work as a cultural activist and visual anthropologist is best seen through his imagery of the Ndebele people which also earned him a National Geographic cover. Magubane has published a number of books on the beauty of South African cultural practices, titles including: “African Renaissance”, “Vanishing Cultures of South Africa” and “AmaNdebele” among many others.

He even worked on Afrikaner culture; despite the ostracism they experienced in post-apartheid South Africa. Magubane loved all people. Dr Peter Magubane was revered all over the world for the work he dedicated his life to.

His honors include, but are not limited to, the following:

- The Coretta Scott King Award (1983)

- The Robert Capa Gold Medal (1986)

- The Missouri Honor Medal for Distinguished service in Journalism from the University of Missouri (1992) for his lifelong coverage of apartheid.

- The Lifetime Achievement Award from the Mother Jones Foundation (1997)

- The Martin Luther King Luthuli Award

- Fellowship by the Tom Hopkins School of Journalism and Cultural Studies

- Honorary Fellow of the Royal Photographic Society in London (2009)

- The Cornell Capa Award from the International Centre for Photography (2010)

- The Nat Nakasa award for Media Integrity (2015)

- The Lucie Foundations Lifetime Achievement Award (2021)

- The Order of Meritorious Service from President Mandela (Silver class)

Dr. Magubane has nine (9) Honorary Doctorates from South Africa’s most prestigious universities and technical colleges, as well as a doctorate from Columbia College in Chicago. He has published over 20 photography books including but not limited to: “Magubane’s South Africa”, “Black As I Am”, “Black Child”, “Soweto Speaks”, “Fruit of Fear”, “June 1976” and “Mandela: Man of the People”. He has had numerous exhibitions throughout South Africa and all over the world, most notably:

- June 16th 1976 at the apartheid Museum in South Africa (2005) and Photo ZA Gallery,

Johannesburg (2017) - Child Labour at the University of Johannesburg (2012)

- Mandela: Man of the People at the United Nations in New York (2010) and at The European Centre for Solidarity (2016) in Gdansk, Poland– the exhibition was opened by former President and Nobel Peace Prize Winner Lech Walesa and the late Ambassador Zindzi Mandela.

In 2014 his first retrospective exhibition consisting of 140 pictures opened at the ABSA Gallery in Johannesburg and travelled throughout South Africa the following year. In 2018 to coincide with the President Mandela Centenary, Dr Magubane selected a hundred of his best pictures of Mandela for an Exhibition in Cape Town at the Gateway to Robben Island. In 2023, the University of Pretoria’s Student Gallery held his final exhibition, “Magubane’s South Africa”—a retrospective of over 150 pictures of his entire career over five decades. The exhibition coincided with Magubane receiving what was his ninth Honorary Doctorate from the University of Pretoria.

Upon awarding Dr Magubane, the Order of Meritorious Service, President Mandela said “For his Bravery and courage during the dark days of apartheid, Peter became a beacon of hope not only to thousands of journalists all over the world but also to millions of people across our country. His commitment to photojournalism helped pave the way to transformation in South Africa, and such efforts are worthy of international recognition.”

In his lifetime, Magubane befriended, mentored, and facilitated the careers of numerous photographers over the years. Even at 91 years of age he continued to teach and inspire people, by holding exhibitions of his work throughout South Africa and globally.

His infectious sense of humor and larger than life laugh belied the hardship he had endured under the oppressive apartheid regime. Magubane was a real character, a man who did not finish school but was taught everything he needed on-the-go in what he called the University of Life. He was a man motivated by the sheer urgency of his times and a deep-rooted love of his people and a belief that freedom was not supposed to be an option.

Magubane was also a family man, insofar as he could be in between all the responsibilities of prioritising the anti-apartheid movement. He loved sitting outside in the garden to soak up rays of sunshine, after which he would lovingly watch the sun set. He was a lover of the finer things in life, good food, antiques and artefacts, sports cars, a stellar pair of shoes and a few glasses of mango juice a day.

Dr Peter Magubane is survived by his cousin, children, grandchildren, great grandchildren, and great-great grandchildren who will all miss him very much.

He leaves behind a loving family, friends, and comrades here in South Africa and abroad. His colossal legacy and archive of imagery is to be cherished, maintained, and treasured. An archive that must be shown to generations and generations beyond him so that we never, ever forget where we’ve come from as a nation.

Long live Peter Magubane, long live!