LANDSCAPE: The country appears to be on autopilot as GNU political wheels wobble in the midst of a great fallout from poor governance, corruption, and uncertainty…

By Jo-Mangaliso Mdhlela

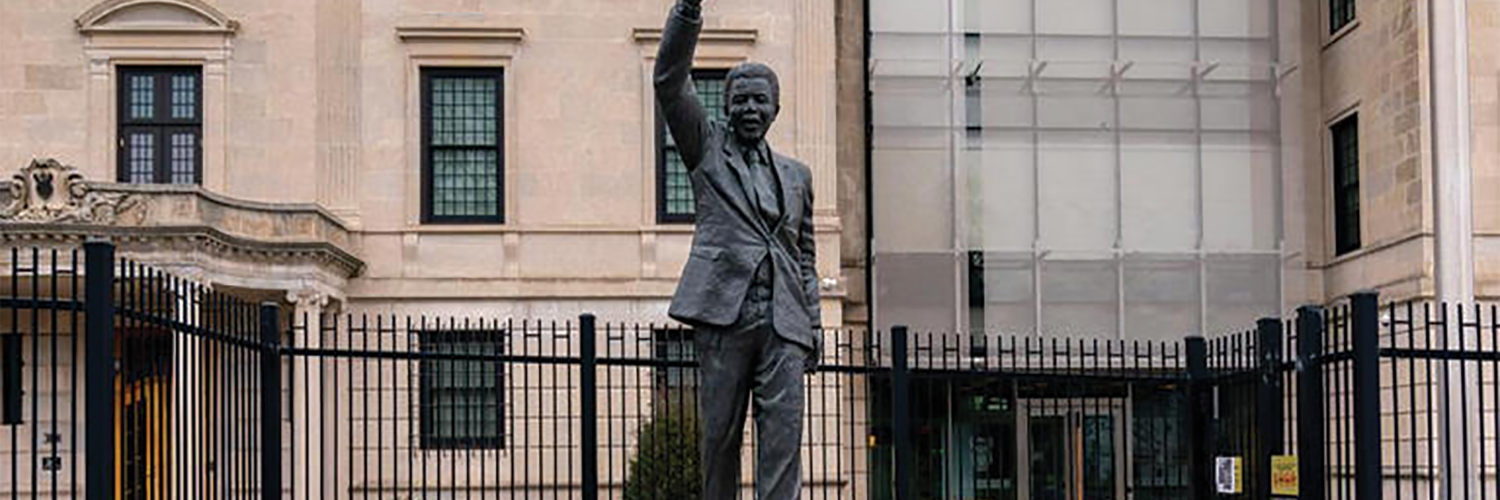

The release of Nelson Mandela from jail on February 11 1990, was a watershed moment – never to be forgotten in the country’s annals, heralding a new political trajectory of democracy accompanied by a promised fair deal for African people, with human rights, economic and social justice its significant green shoots.

Instead, hopelessness pervades 31 years later, with the country ridden with acts of violence; lawlessness is on the increase; poor governance, gender-based violence, and corruption at all tiers of government made up of national, provincial, and local governments.

As political wheels come off, and serious problems of poor governance facing the country, the national foundations made up of – among others – Nelson Mandela Foundation, Thabo Mbeki Foundation, Ahmed Kathrada Foundation, Desmond and Leah Tutu Legacy, Robert Mangaliso Trust, Steve Biko Foundation, support the initiative to have all South Africans to converging to face the beast of corruption together – and “develop the road map and agenda for the national dialogue”.

In stranger ways, the new current political system is also unleashing dynamics that are increasingly becoming toxic, failing to be driven by the spirit and letter of the Constitution.

The 1994 miracle was politically unique. Former president Nelson Mandela and his ANC comrades were shrewd to outwit the adversary, National Party, arguably for the common good of all South Africans, even as the outcome of their deal-making were –in some black political quarters – labelled “sell-out”. Today, politics tend to be driven by self-interests, skewed ideologies contrary to developing country ideals, with incompetence especially in metropolitan municipalities sabotaging the nation-building dream.

But, this should not mean Mandela and his company did not encounter political difficulties. There were many within the parties and outside of it who expressed reservations and skepticism about the value of the much-touted Convention for a Democratic South Africa (Codesa), and this continues to this day, given the realities that the 1994 settlement has failed to yield cherished outcomes.

During the 1994 negotiations, Joe Slovo, the South African Communist Party strategist, had hoisted to the top echelons of the liberation movement, both in the ANC and SACP, conceived for the ANC negotiators a strategy which took the form of “sunset clause”, by which the ANC would for a period of time allow political power, which rightful belonged to the ANC and other liberation movement to be shared with the enemy camp.

In terms of this arrangement, the ANC and the National Party would work together, and for a short period of five-years, form a government of national unity (GNU).

This thinking won the day – the government of national unity was formed, with the National Party allowed to share the spoils of the political struggle waged by the liberation movement.

On April 27, 1994, the ANC, with a massive majority, won the first democratic national elections, and formed the government of national unity, despite their landslide victory. Yet, in comparison, and nearly 31 years later, the ANC is in a much weaker position this time around. Thanks to a poor showing in the May 29 national and provincial elections of 2024, amassing a weak 40% victory.

Today the ANC has no political wherewithal to claim the authority it commanded after the 1994 elections. Instead, it has become a fragile party – a far cry from the party that was gloriously led by Mandela.

This may partly explain why former president Thabo Mbeki, in his pragmatism, called for a national dialogue which will galvanise all sectors of society to be participants.

“Our people must get together to talk about a South Africa they need and the South Africa they do not want,” Mbeki told a conference of the South African Communist Party late last year.

Mbeki’s call for a dialogue resonated well with the SACP faithful – the same faithful who see the GNU as a “sell-out” position, incongruent with the SACP philosophy of refusing to work with the DA, a political part they regard as the “the enemy of the people”.

Could it be that the resultant frosty relations between the SACP and ANC are irresolvable?

One must wonder what role the SACP would want to play in a national dialogue that would conceivably not exclude the DA, the white-dominated party they hate with a passion.

Mbeki, though, has made it clear that the national dialogue is for all South Africans, from all walks of life, and this, by definition, must also mean the DA will indeed be part of the dialogue, if it does take place.

Where does this leave Ramaphosa, the proponent of GNU and national dialogue? Where does this leave the SACP, the communist party’s apparent uncompromising position on the DA, whatever the circumstances?

In the proposed national dialogue, the country will need wise men and women, to restore the confidence that came with the promise of a better life in 1994 when Madiba was at the helm.

Mandela was trusted as the epitome of a true leader and statesman – something that rubbed off on the party he led. But that trust has since waned.

How can leaders of such low stature as former president Jacob Zuma engender any trust?

Now the political wheel, 31 years later, has come a full cycle, returning to its starting point, April 27 1994, the year which spawned democracy and constitutionalism and great hope.

Is political compromise possible to be attained at the proposed national dialogue?

Last year’s May 29 national and provincial elections outcomes demonstrated – beyond doubt – that South Africans no longer trust the country’s political players, denying the ANC outright victory in the national parliament and in Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal provincial legislatures.

South Africa, in a manner of speaking, is politically on its knees. It has lost its shine. Long gone is the Madiba magic. No Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe either, to save the ship by weaving his charisma and providing deep political insights. Nor is there Oliver Tambo or Steve Bantu Biko to offer philosophical thinking.

For now, we will watch this space – whether Mbeki’s and Ramaphosa’s national dialogue instrument will take off to try to salvage the lost political ground, compounded by South Africans’ lack of confidence in the 31-year-old democratic process and the great promise betrayed by corruption and spells of disastrous governance.

*Mdhlela is an independent journalist, an Anglican priest, an ex-trade unionist, a social justice activist