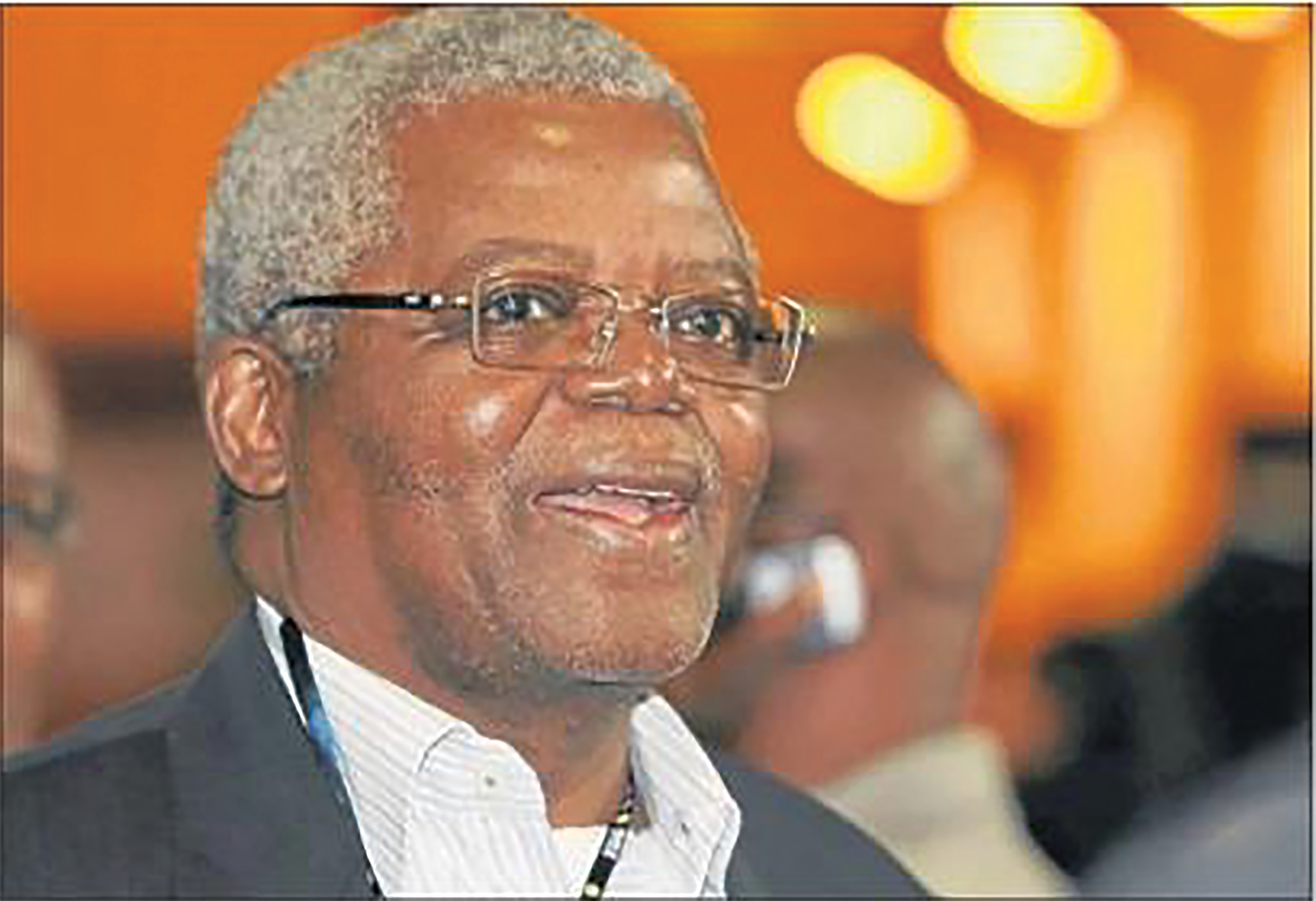

PERSPECTIVE: May 25 commemorations should shift focus from emotional fervour to a future scientific and technological focus, argues struggle stalwart Father Smangaliso Mkhatshwa…

By Smangaliso Mkhatshwa

There was ululation when visionary African leaders launched the Organization of African Unity (OAU) in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, in 1963. The message was loud and clear – Africa would be liberated and would no longer be a conveyor-belt for colonialism.

On the contrary, it would support movements who fought for the interests of the total liberation of Africa. To some extent, this was the culmination of a dream by Kwame Nkruma and Patrice Lumumba of a seminal United States of Africa.

When the 21st century dawned on us, we realised that economic freedom was central to making Africa a world player in every respect, especially in a globalised environment.

South Africa was given the honour of hosting the launch of African Union (AU), a successor to OAU, in 2002. As we celebrate Africa Day (May 25), we need to ask ourselves some critical questions: What political, social and economic progress has Africa made during this honeymoon period?

Some analysts think that, while Africa has made some positive strides, it has also retrogressed. One only has to look at the economic and political stranglehold that some European countries still have on their former colonies.

Without romanticising Africa’s contribution to global civilization, it is only fair to refer to an aspect of that glorious history. When ancient Roman scholars spoke about Africa they did so in glowing terms, such as “ex Africa semper aliquid novi” – loosely translated, out of Africa there is always something new.

They were aware of Africa’s contribution to ancient civilizations, especially in science, mathematics, medicine, architecture, engineering, philosophy and the arts. Ancient Egyptians invented mathematics and divided it into arithmetic, algebra and geometry. This knowledge was later passed on to the Greeks.

Egyptians also engaged in engineering, construction, shipbuilding and architecture. They then imparted their vast knowledge to the Greeks, most of whom became very famous, such as Plato, Pythagoras, Eudoxes, the mathematician and astronomer, Hippocrates and many others whose work reflected the great and pervasive influence of the black Africans.

The great Egyptian civilisation was followed, millennia later, by the civilizations of Nubia Aksum, Mapungubwe, Ghana, Mali and Great Zimbabwe. In contrast, the European “pseudo historians” of the 19th century argued that there were no human beings on earth who were divinely endowed with intelligence, fortitude and wisdom except them. About blacks, they were absolutely sure that these were not only incapable of making any significant contribution to human civilization, but were in fact sub-humans.

In this regard, the historian Basil Davidson observed that: “None of this rather fruitless argument, as to the skin colour of the ancient Egyptians before arrival of the Arabs in the seventh century AD would have arisen without the eruption of modern European racism during the 1830s.

“It became important to the racists, then and since, to deny Africans any capacity to build a great civilization. We should dismiss all that. What one needs to hold in mind is the enormous value of ‘African Genius’.”

Pixley ka Isaka Seme also added his voice when he addressed Columbia University students in 1906: “Come with me to the ancient capital of Egypt. Thebes, the city of one hundred gates. The grandeur of its venerable ruins and the gigantic monuments of other nations. All the glory of Egypt belongs to Africa and her people.

“It is not through Egypt alone that African claims such unrivalled historic achievements. I could have spoken of the pyramids of Ethiopia, which, though inferior in size to those of Egypt, far surpass them in architectural beauty; their sepulchres, which evince the highest purity of taste’, and of many prehistoric ruins in other parts of Africa.”

Ongoing archaeological excavations reveal an ancient and pre-colonial Africa of considerable achievement. The Mapungubwe society, once situated in parts of Limpopo and considered the foundation of Zimbabwe culture, has been associated with the Iron Age, with iron, copper and gold smiths among its artisans. The Mapungubwe people traded with India and China, among other civilizations.

Then followed the ruthless plunder and subjugation of Africa through slavery, colonization and imperialism. These vicious manoeuvres did not go unchallenged.

The challenges to European supremacy culminated in the emergence of African movements for liberation. After South Africa achieved freedom in 1994 discussions got under way to create an organisation to focus primarily on Africa’s development in its various forms. That led to the launch of the AU in 2002.

The AU through the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD) could address some of the major challenges. Since many African states are dependent on donors to balance their budgets, the challenge of fiscal independence is of paramount importance. Many African economies are still extensions of their erstwhile colonial economies. To be honest, Africa is not yet free.

For instance, how do we allow China to build and equip the AU office in Ethiopia for free?

Despite having all possible natural resources to make Africa a giant global economic player and improve the lives of over 1 billion African inhabitants, we are still victims of poverty, fragile economies and vulnerability to foreign interests.

There is something both cynical and ironical about AU’s readmission of Morocco to its ranks while it maintains its colonial stranglehold over the people of Sahara.

We cannot reduce Africa Day to cultural exhibitions, art, traditional music and dance. We should be holding massive demonstrations to demand self-determination for oppressed people of Western Sahara, including the immediate expulsion of the Moroccan ambassador from South Africa. Otherwise we are hypocrites.

The celebration of Africa Day should take a different form. It should shift focus from emotional excitement to a future scientific and technological approach. It should shift from song and dance to a critical reflection on Africa’s consciousness and reappraisal of its destiny in the world.

* Mkhatshwa is former deputy minister of education, former Tshwane mayor, former SACBC secretary general, and now chairman of Moral Regeneration Movement