INNOCENCE: The exonerations involve former death row inmates who had either been acquitted of all charges that placed them on death row or had been dismissed by the prosecution in the United States since 1973…

By Daniel Payne

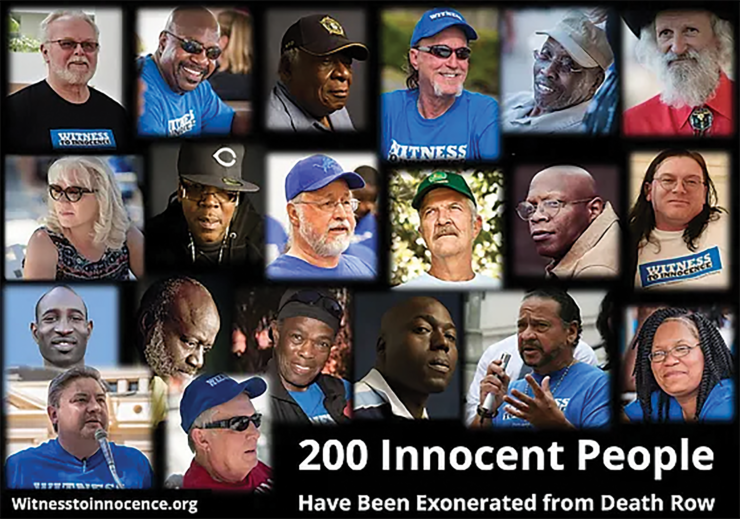

Opponents of the death penalty in the United States are celebrating a milestone as the country marks the 200 cases of a prisoners saved from the death row in roughly 50 years and more states continuing to abolish capital punishment.

Catholic Mobilising Network (CMN), which advocates ending capital punishment in the United States, said in a press release this month that California prisoner Larry Roberts had become “the 200th death row exoneration since 1973.” Roberts had been on death row since 1983 after his fellow prisoners claimed he killed both a prison guard and another inmate.

Roberts was wrongfully convicted in 1983 for the murder of a fellow prisoner and prison guard at the California Medical Centre in Vacaville, California. The only witnesses to these stabbings were fellow prisoners who testified against Roberts. Following their testimony, he was sentenced to death for both killings. Years later, the California Supreme Court overturned Roberts’ conviction for the death of the prison guard, but left his death sentence in place.

After 41 years, the California Attorney General’s Office agreed with a US district court judge who granted Roberts a new trial, saying it will not retry him.

Roberts’ exoneration is a powerful reminder of the fallibility of the death penalty, and one more reason 50% of the American public no longer believes their government can fairly use the death penalty.

CMN executive director Krisanne Vaillancourt Murphy said in the press release that the 200 exonerations were the result of “the tireless efforts of faithful advocates and committed lawyers.”

Exonerations, according to CMN, are cases involving former death row inmates who have, since 1973, either been acquitted of all charges related to the crime that placed them on death row or had all charges related to the crime that placed them on death row dismissed by the prosecution.

It also includes prisoners who have been granted a complete pardon based on evidence of innocence.

“[W]hile we praise God that these lives have been spared, we also remember the many individuals — both innocent and guilty — who did not, and will not receive the same grace, whose lives are discarded by a system determined to throw them away,” she said.

Murphy told CNA in a phone interview that the hundreds of exonerations are “a significant indicator of the brokenness of the death penalty.”

On its website, CMN says it plays “a central role in state and federal repeal campaigns, collaborating closely with the US Conference of Catholic Bishops, state Catholic conferences, local dioceses, religious communities, and secular abolition groups.”

The group helps spearhead “prayer vigils, press events, webinars, and speaking tours” against the death penalty; it also works at “connecting key players, like church leaders and abolition movement organisers.” Asked if the anti-capital punishment movement is optimistic about its efforts, Murphy said: “Undoubtedly.”

She pointed out that nearly half of all American states, as well as the District of Columbia, have abolished the death penalty.

“The trends are moving in our favour,” she said. “The use of the death penalty is decreasing, as are the people being sentenced to death. The repeals are much more bipartisan than they’ve ever been.”

“I think Americans are getting less and less tolerant of this practice,” she said. “For all these reasons we’re continually encouraged.”

Among the groups with which CMN has partnered against the death penalty include Witness to Innocence, which works “to empower exonerated death row survivors to be the most powerful and effective voice in the fight to end the death penalty and reform the justice system in the United States.”

Herman Lindsey, the executive director of Witness to Innocence, was sentenced to death in Florida in 2006 for murder. The state Supreme Court subsequently exonerated him in 2009, ruling that Florida “had failed to produce any evidence in this case placing Lindsey at the scene of the crime at the time of the murder.”

Lindsey told CNA in a phone interview that Witness to Innocence offers exonerees — many of whom have trouble finding work — a chance for employment while speaking out against capital punishment.

“We run a lot of campaigns at one time,” he said. “We’re involved in a lot of cases. We work with each and every state, and with attorneys on the cases.”

“If it’s a case that’s out there, most likely we’re active in it in some type of way, somehow,” he said.

Murphy said there are “exciting things on the horizon for Catholics to help us mobilize and speak on this issue more effectively.”

“We’ve got October10 coming up, the World Day Against the Death Penalty,” she said. She praised Pope Francis for making it “explicit” that Catholics should work against the death penalty in the upcoming Jubilee Year of 2025.

The death penalty “is at odds with the Christian faith and eliminates all hope of forgiveness and rehabilitation,” Murphy said. “We should be thinking and acting on this issue in the Jubilee Year.”

Both Lindsey and Murphy expressed happiness at the milestone 200th exoneration while lamenting the need for those exonerations at all.

“It’s a great thing, but it’s a bad thing, that we reached the 200 mark,” Lindsey said. “But the good thing about it is it shows that organisations and attorneys are working hard.”

Murphy, meanwhile, said she was “delighted that there has been success in more cases to get people off of death row.” – CNA and additional info from the Death Penalty Information Centre

GEORGE STINNEY – NO GREATER INJUSTICE

EXONERATION: Remembering the execution of the 14-year-old boy, 80 Years Later

George Stinney

June 16 this year marked 80 years since South Carolina executed 14-year-old George Stinney Jr Historical reports indicate that on March 24, 1944, Stinney and his younger sister, Aime, were playing outside when two white girls approached them, asking where they could find a particular flower.

Neither Stinney nor his sister knew where the young girls could find these flowers and they quickly moved along. That evening, when both young girls failed to return home, a search party was sent to find them. Stinney and his family joined the search party, and he mentioned to another searcher that he had seen the girls earlier in the day.

The next morning, after a pastor’s son discovered the bodies of both girls in a shallow ditch, Stinney was arrested and charged with their murders. According to police, Stinney confessed to bludgeoning both girls to death despite the absence of any physical evidence connecting him to the crime.

The boy was charged with capital murder and rape, tried, convicted, and executed in South Carolina’s electric chair in just under three months.

Just days after Stinney’s arrest, his father was fired from his job and the family was forced to flee town because of threats of violence.

On March 26, a white mob attempted to lynch Stinney, but failed to do so only because he had already been moved to a jail in a different town. A month later, Stinney went to trial, but his family and other African Americans were not allowed to enter the segregated courthouse.

Stinney’s attorney had no experience representing capital defendants and failed to call any witnesses in his defense. The prosecutor only presented testimony from the local sheriff, who described the boy’s alleged confession.

After just 10 minutes of deliberation, an all-white jury sentenced Stinney to death for rape and murder. Governor Olin Johnston refused to grant him clemency, and he was executed by the electric chair on June 16, 1944. Newspapers reported that guards had trouble getting Stinney strapped into the electric chair built for adults, as he stood at just 5 foot 1 and weighed 95 pounds.

When the executioner flipped the switch and the initial 2 400 volts surged through Stinney’s body, the oversized mask placed on his face slipped, exposing the tears streaming from his frightened eyes. He remains the youngest person executed in the United States during the 20th century.

Stinney’s siblings always maintained that he was not involved in the murders, but it was not until 2004 when legal efforts to exonerate Stinney began. In October 2013, attorneys for the Stinney family filed a petition asking the court to overturn the guilty verdict. Just three months later, Sumter County Circuit Judge Carmen Mullen held a two-day evidentiary hearing to determine whether Stinney received a fair trial.

George’s sister, Aime Ruffner, repeated the same story she had told since 1944, noting that she remembered the day well because “no white people came around” to the Black side of town.

“Somebody followed those girls and killed them,” she told the court.

In December 2014, Judge Mullen formally vacated Stinney’s capital conviction, determining that he was deprived of due process throughout his trial. In her order, Judge Mullen wrote that “Stinney’s appointed counsel made no independent investigation, did not request a change of venue or additional time to prepare the case, he asked little or no questions on cross-examination of the State’s witnesses and presented few or no witnesses on behalf of his client based on the length of the trial. He failed to file an appeal or a stay of execution. That is the essence of being ineffective…”

Ultimately, Judge Mullen could “think of no greater injustice than the violation of one’s Constitutional rights which has been proven to [her] in this case.”

Katherine Robinson, one of Mr. Stinney’s sisters, said that “when we got the news, we were sitting with friends…I threw my hands up and said, ‘Thank you, Jesus!’ Someone had to be listening.

It’s what we wanted for all these years.” Ms. Robinson said that despite the many years between her brother’s execution and exoneration, she has great memories of the time they spent together.

“I’m happy for this day because it’s been such a long time coming, but then I cringe when I go back into that childhood and think of George back in the day,” Ms. Robinson said.

“He had no one to help him. I get chills every time I think about it.” – Source: Death Penalty Information Centre