FALL FROOM GRACE: Cronje’s story re-examined in Sport’s Strangest Crimes on BBC Sounds is a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma

By Sports Reporter

Inside a wood-panelled annex of an Edwardian building in Cape Town the stricken figure of Hansie Cronje lay crumpled on the floor.

Away from the flashbulbs, and the media feeding frenzy, in the bowels of the Centre of the Book in the city’s legal district, the exhausted former South Africa cricket captain, clad in a charcoal suit, had collapsed in tears.

His father Ewie and brother Frans tried to comfort him. Hansie had just given evidence to the King Commission – the inquiry charged with investigating match-fixing allegations in cricket of which he was at the centre.

Just under two years later and both Ewie and Frans would be pallbearers at Hansie’s funeral following his shock death in a plane crash.

It is now 25 years since Cronje’s life was turned upside down, and cricket was thrown into crisis, by a scandal which rocked the sport.

Cronje’s story, re-examined in Sport’s Strangest Crimes on BBC Sounds, is a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.

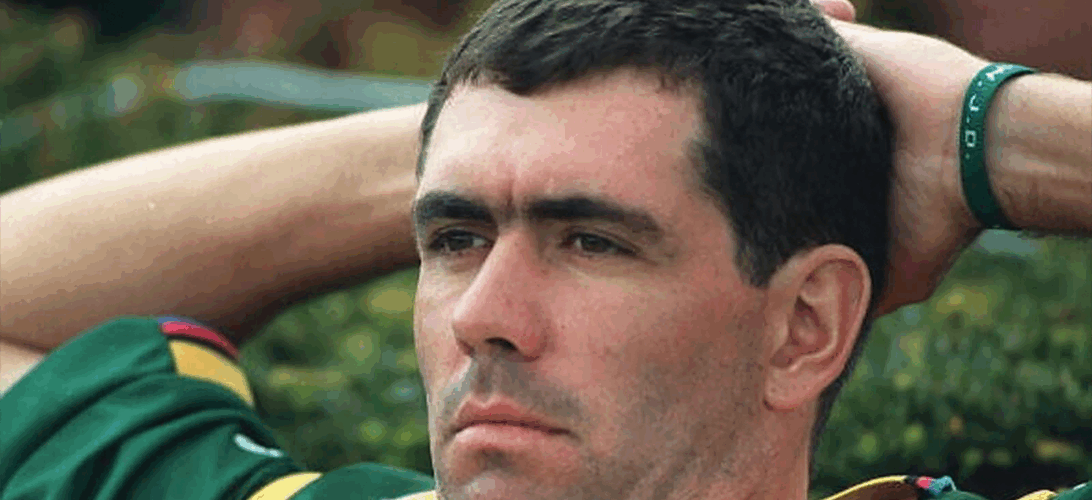

Wessel Johannes ‘Hansie’ Cronje was born into a sporting, and deeply Christian, family in Bloemfontein.

Cronje was educated at the prestigious Grey College where he was head boy, captained the school in both rugby and cricket, and was earmarked for great things..

Cronje was appointed Orange Free State captain aged 21 and the batting all-rounder soon became a part of the post-apartheid South Africa team which re-emerged on the international stage.

He was handed the captaincy of the Proteas in 1994 and his astute tactics and calm assurance gave him a statesmanlike air as he turned the team into a formidable international side.

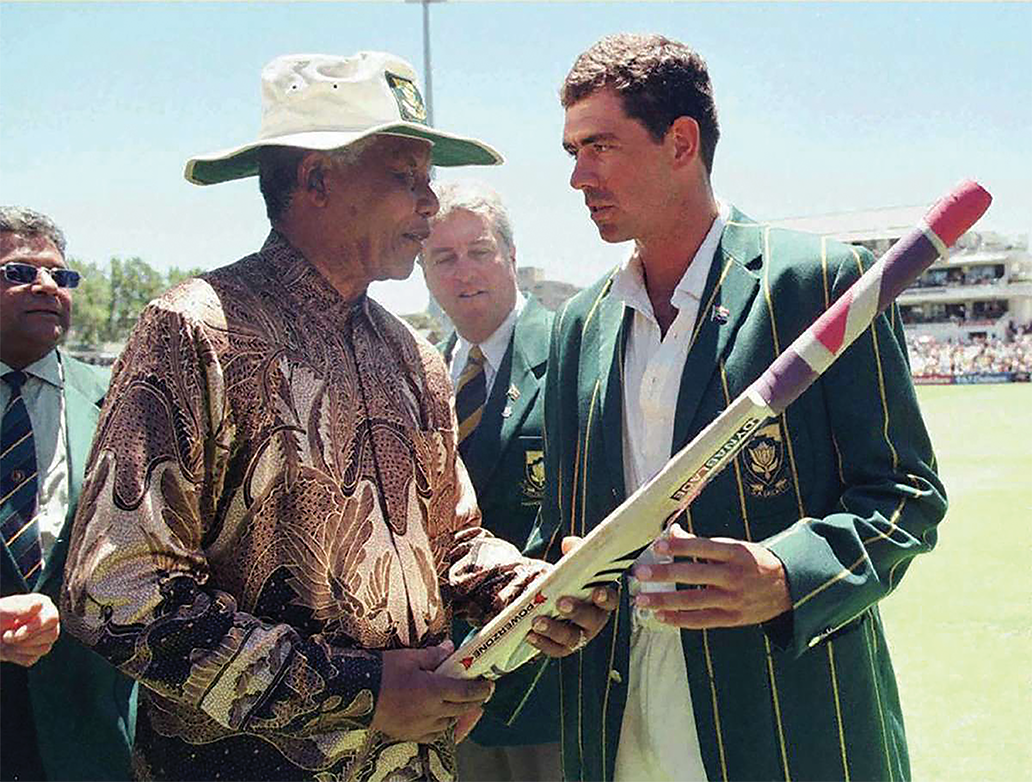

Cronje also forged a close personal relationship with president Nelson Mandela.

During a time when Afrikaner politicians began to disappear from view, Cronje was one of those from that community who filled the vacuum.

Mandela singled out Cronje in 1996 for the “excellent manner” in which he “led the national team” at a time when “sport had played a role in uniting our country”. Cronje was a figure who seemed to transcend cricket. However, there was a darker side to Cronje. Especially when it came to money.

Good looking, and extremely approachable, Cronje was a sponsors’ dream and the endorsements flowed. Yet Donald said Cronje was a “tight git” when it came to things as simple as buying post-match drinks.

Cronje’s frugality did not just extend to not getting a round in, though. It bordered on the obsessive. He would receive free clothing and kit as part of a sponsorship deal with Puma but would sell any unused items to younger players, rather than giving it away for nothing.

That love of money meant Cronje was also one of the most accessible cricket captains around and he was regularly visited by people, particularly while on tour in South Asia.

It led to dealings with unscrupulous characters. In particular those involved with betting, and there was an early portent of what was to come in 1996.

Fast forward to Nagpur in 2000, Cronje attempted to coerce South Africa batter Herschelle Gibbs and seam bowler Henry Williams into spot-fixing offences. Both men agreed, but subsequently did not carry out the instructions.

The most infamous of Cronje’s dealings with bookmakers came during the rain-affected fifth Test between South Africa and England at Centurion Park in early 2000. Cronje immediately accepted the figure Hussain asked for.

Cronje’s innovative action to create a result on what otherwise would have been a dead final day of a Test largely drew praise, even if did not quite sit right with everyone.

When Delhi police released transcripts of recorded conversations between Cronje and Indian bookmaker Sanjeev Chawlar in early April 2000 it was met with denials from the man himself and South African cricket officials, and wider disbelief.

At 3am on 11 April 2000 he confessed to Rory Steyn, a South African security consultant working for the Australia cricket team, in a Durban hotel where the pair were staying. “He had a handwritten document and said ‘you may have guessed, but some of the stuff that is being said against me is actually true’.”

A couple of months later, Cronje attended the King Commission where he was offered immunity from prosecution in exchange for full disclosure.

During three days of cross examinations, broadcast on television and radio, which gripped South Africa and the cricket world, Cronje gave his side of the story.

Or at least some of it, given the input of his own lawyers.

He admitted to taking large sums of money, as well as accepting a leather jacket for his wife Bertha, in exchange for giving information to bookmakers and asking his team-mates to play badly.

“To my wife, family, and team-mates, in particular, I apologise,” he said during a rather robotic reading of an opening statement lasting 45 minutes.

Cronje was banned from cricket for life, unsuccessfully challenging the suspension. Further investigations into the truth of what Cronje said during the inquiry were halted when he died in a plane crash in June 2002.

Cronje had boarded a small cargo aircraft in Johannesburg which went down in mountainous terrain amid poor weather conditions while attempting to land at George airport.

His death was put down to weather, pilot error and possible instrument failure, but nevertheless prompted conspiracy theories. A generation has now passed since the former South Africa captain’s murky involvement with bookmakers came to light, but his legacy remains a complex one.

His death at the age of 32 meant he was denied an opportunity at redemption within a sport he felt so connected to. For some Cronje had been vulnerable, and had the anti-corruption measures which came in the wake of his fall from grace been in place, his story might have been different.

Those close to him felt that once the depression following the King Commission lifted, Cronje’s life path had altered course for the better.

• The full six-part series of ‘Sport’s Strangest Crimes – Hansie Cronje: Fall From Grace’ is available on BBC Sounds.