TEMPERAMENT: About one in three people “highly sensitive,” meaning they feel sights, sounds, and emotions more deeply than others…

By Own Correspondent

LONDON — Nearly one-third of people possess a personality trait that is linked with depression and anxiety symptoms, yet it’s often overlooked in treatment.

A new systematic review and meta-analysis of existing studies reveals that “highly sensitive” people tend to show moderate associations with mental health problems.

Researchers analysed 33 studies involving more than 12 000 people and found consistent positive connections between heightened environmental sensitivity and common mental health disorders. They argue that sensitivity represents a measurable trait that may matter for psychological well-being.

Led by scientists from Queen Mary University of London, the research shows moderate links with depression, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, and social phobia. The connection was similar in strength for both depression and anxiety.

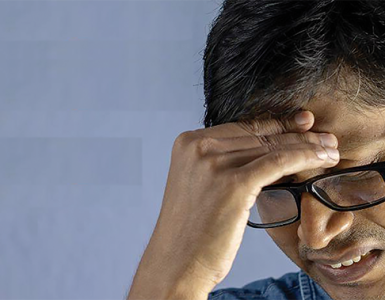

Environmental sensitivity describes people who process sensory information more deeply and react more strongly to their surroundings. These individuals often notice subtle environmental changes, feel overwhelmed in busy environments, and experience intense emotional responses to both positive and negative situations.

This trait exists on a spectrum. About 29% of people show low sensitivity, 40% show medium sensitivity, and 31% display high sensitivity, according to previous research.

Scientists measure this trait using questionnaires that include questions such as “Are you more than others affected by moods of other people?” and “Do you become unpleasantly aroused when a lot is going on around you?”

The concept traces back to Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung, who described “innate sensitiveness” in 1913, but systematic research only began in the 1990s.

Brain imaging studies have revealed heightened activity in regions associated with empathy, social processing, and reflective thinking among sensitive individuals.

The analysis found moderate connections between sensitivity and both depression and anxiety.

Individual studies showed connections ranging from weak to strong, but all studies that measured overall sensitivity found positive links. Results varied across studies, but the general pattern remained: higher sensitivity typically went hand-in-hand with more mental health symptoms.

The review also identified positive associations with obsessive-compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, agoraphobia, and social phobia, though these relationships varied in strength.

Different aspects of sensitivity showed varying relationships with mental health. The tendency to feel easily overwhelmed and having a low threshold for sensory input showed stronger connections with psychological problems than aesthetic sensitivity, which is the capacity to be deeply moved by art, music, or beauty.

Currently, most therapists and doctors don’t routinely check for environmental sensitivity, potentially missing an important factor in their patients’ psychological makeup. Since about 31% of the general population show high sensitivity, this trait may also be relevant for many people in clinical settings.

Previous smaller studies have indicated that highly sensitive individuals may respond differently to psychological treatments. Some research shows they may benefit more from certain types of therapy, particularly mindfulness-based approaches that help manage overstimulation and emotional reactions.

As the researchers write: “Better knowledge on the role of individual differences in sensitivity for mental health may not only inform theory but could also have practical implications” for treatment planning and how well interventions work.

The analysis has important limitations. Most studies relied on college students, which may not represent the broader population. Most participants were young, educated women, so the results may not apply as well to men and older adults.

Nearly all studies looked at people at one point in time, making it impossible to determine whether sensitivity causes mental health problems or whether having mental health issues makes people more sensitive. Only five studies followed participants over time, and just two examined people actually receiving mental health treatment.

The researchers acknowledge that all studies relied on questionnaires, which can be affected by how people see themselves and want to present themselves.

While this doesn’t prove that sensitivity causes mental health problems, it suggests this personality trait deserves more attention in mental health research and potentially in clinical practice. For people who experience the world more intensely than others, understanding this aspect of their temperament could inform how they approach their mental health care.