SCENARIO: Lenacapavir, a twice-yearly prevention injection, is one of the most promising tools yet in the fight to end the disease – but a lack of ambition and unjustifiable secrecy over pricing is holding it back, argue three leading health activists…

By Fatima Hassan, Leena Menghaney and Bellinda Nkoana

Imagine a new HIV prevention tool existed that could – if it reached the right people – flick the switch to prevent almost all new HIV cases across the world.

You would expect every health system and government to be doing all they can to roll it out to everyone as quickly as possible, regardless of the challenges, right? The good news is that this scenario is not merely in our imagination because we actually have that tool today. The bad news? The rollout of this breakthrough HIV prevention jab is moving at a glacial pace.

Lenacapavir, a twice-yearly antiretroviral-containing injection, is one of the most promising tools yet in the fight to end AIDS. Data from two major trials released last year showed it offers near-complete protection against HIV infection for some of the most vulnerable groups: young women, men who have sex with men, sex workers, and transgender and gender-diverse people.

Trials that test the effectiveness of the jab as prevention in people who inject drugs are also underway. For communities still bearing the brunt of new infections, it could be a game-changer.

Take South Africa as a case in point. Modelling studies suggest the impact could be transformative. If two to four million HIV-negative people here used lenacapavir annually over the next eight years, new infections could dramatically fall, with rates low enough that experts would consider it significant enough to end AIDS. And yet, the current rollout targets look worryingly timid, particularly for vulnerable communities.

According to the National Department of Health, South Africa’s projected initial target for the first two years of the roll out (April 2026 – March 2028 and subject to registration or interim approval by the South African Health Products Regulatory Authority) of just under 500 000 people, includes the general population and certain vulnerable or key risk population groups – for the latter, the targets are woefully low: 69 799 sex workers, 37 857 transgender people, and 155 946 gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men.

This barely scratches the surface of the actual need in vulnerable populations. At this rate, access will be severely rationed, and the epidemic will continue to outpace us.

One reason the roll-out cannot be on a mass scale is, not just due to an absent political will, but also because the company that holds the patent, Gilead Sciences, is rationing access. And, until a sufficient number of generics come on to the market, voluntarily or through compulsory measures, Gilead will continue to call the shots.

The Trump administration’s funding cuts earlier this year left ambitious plans to roll out lenacapavir in several countries in the Global South in the dust. In response, South Africa, in consultation with the Global Fund for AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria (Global Fund) and indirectly with Gilead, announced plans to repurpose R520-million from an existing Global Fund grant to buy lenacapavir for HIV prevention. But, despite South Africa being asked by the Global Fund to budget $30 per dose ($60, roughly R1 050, per person per year) as its contribution, no one knows the total price the Global Fund is paying Gilead.

Such pricing secrecy is unacceptable, especially when health ministries in low- and middle-income countries are already squeezed by the massive US government funding cuts and debt crises.

Countries excluded from the Global Fund’s supply agreement and Gilead’s inadequate mechanisms for allowing generic competition (they exclude several countries and only a few companies were licensed) will be left to negotiate directly with Gilead, facing the prospect of unaffordable “tiered” prices designed to maximise profit – eerily similar to the COVID vaccine inequitable access debacle. Millions who need HIV prevention could face rationing, with health providers forced to leave the most vulnerable populations behind.

The Global Fund’s willing decision to shield Gilead’s pricing from public disclosure undermines accountability and risks reversing years of hard-won progress towards transparency in medicine pricing in the Global South and elsewhere. This is a dangerous precedent for the global HIV movement as pharmaceutical multinational companies are finding new ways to normalise price secrecy – and the Global Fund has just approved that tactic.

While civil society in Global South countries such as South Africa are defending the right to know how public funds are spent, global institutions like the Global Fund in Geneva, are enabling practices that give pharmaceutical corporations a free pass.

The push to normalise secrecy, particularly when public or donor money is involved, should ring alarm bells. If international actors are serious about equitable access, then price transparency must be non-negotiable. Anything less erodes public trust and hands undue power to pharmaceutical companies at the expense of public health. Transparency is also necessary to ensure that the price we pay is fair and justified, because public money should not subsidise Gilead’s profiteering.

All this comes at a time when global health financing is under severe strain. Deep cuts in HIV/AIDS funding have already cost tens of thousands of lives across multiple countries. But rationing prevention is a false economy because the cost of new infections, in lives and long-term treatment, will far outweigh the investment required to scale up prevention now.

As delegates convene this week at the SA AIDS Conference, they must publicly call out the demand for price secrecy from Gilead and the Global Fund for what it is: bullying. It must also raise the funds, domestically and internationally, to pay for lenacapavir for all who need it. Two million people at minimum should be the national target – four times the glacial rollout pace the Global Fund is proposing at present.

The lesson from history is clear: When lifesaving HIV treatment was delayed, millions died needlessly. We cannot afford the same mistake with HIV prevention. – Spotlight

* Hassan, Menghaney and Nkoana are all part of the global LEN-LA for All Coalition

PUBLIC URGED TO JOIN FIGHT AGAINST HIV AND TB

PROGRESS: Govt. exploring partnerships with BRICS nations to address funding deficits…

By Monk Nkomo

South Africa carried the highest HIV and TB burdens globally with a higher prevalence among people aged 15 and 49 with adolescent girls and young women recording the highest new infections per week, according to Deputy President, Paul Mashatile.

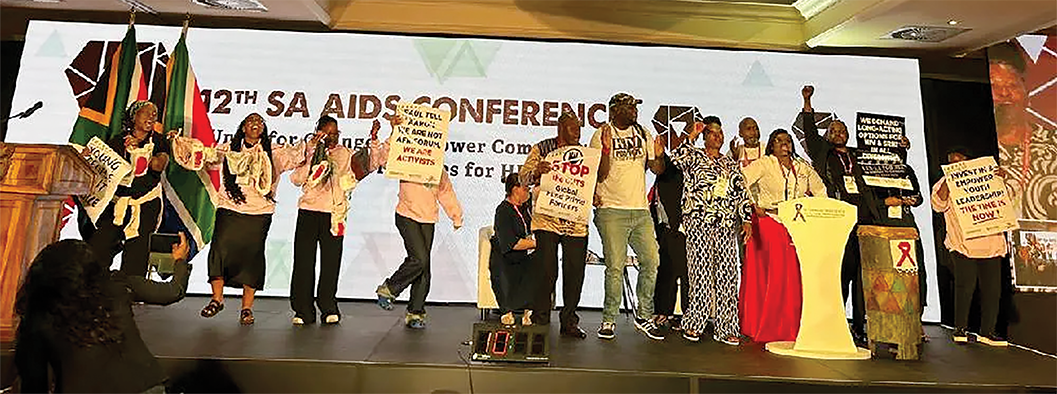

Addressing the 12th SA Aids Conference at Emperors Palace in Ekurhuleni, he said empowering communities and redefining priorities for HIV\AIDS the government strategies must prioritise giving power and resources to those who were most affected. ‘’ This means moving away from a top-down , clinic-centred approach and towards one that was community-owned and driven.

Statistics released in March this year revealed that a total eight million people were living with HIV in South Africa.

The theme of this year’s conference, “Unite for change – empower communities and redefine priorities for HIV/Aids”, resonated deeply with the shared commitment South Africans held within their hearts, said Mashatile. It underscored the proactive role citizens must play in coordinating the responses to HIV, TB and STIs, cultivating partnerships and promoting community involvement.

This required extensive community participation in programme implementation and oversight to ensure that treatments addressed structural barriers and met different population needs.

Mashatile reiterated that as Government, they acknowledged the impact of US funding cuts on their response and they were diligently working to preserve their achievements in the fight against HIV/Aids. While these accomplishments may be momentarily jeopardised, they would prevail.

The government was now concentrating on augmenting their domestic funding, initiating national campaigns and exploring partnerships with BRICS nations and the private sector to address the funding deficits.

‘’In redefining priorities for HIV/AIDS, we must take advantage of our National Strategic Plan for HIV, TB, and STIs (NSP 2023-2028). This plan emphasises the importance of enhancing prevention and treatment efforts, integrating community-led initiatives, fortifying health systems, and focussing on evidence-based, data-driven strategies’’, said Mashatile.

This translated into deliberate action to invest in prevention strategies that were evidence-based and tailored to the diverse needs of different communities. The government must ensure access to comprehensive and inclusive healthcare services that left no one behind. Authorities must continue to champion education, awareness and destigmatisation efforts that break down barriers and fostered a culture of understanding and support.

‘’Additionally, it is essential to concentrate on harmonising our objectives with the existing Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) aimed at health equity. This means swift reaction and prioritising key populations exhibiting high-risk behaviours through community engagement and support, while striving to meet the ambitious 95-95-95 targets for testing, treatment, and viral suppression for everyone’’.

Mashatile said It was therefore important that, as they gathered at this conference, they should acknowledge the progress that had been made in the fight against HIV/Aids. They must also recognise the challenges that continued to persist towards meeting the UNAIDS 95-95-95 targets. These targets were a global strategy for ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030, aiming for:

• 95% of all people living with HIV to know their status;

• 95% of those who know their status to be on sustained antiretroviral treatment and

• 95% of those on treatment to be virally suppressed. Viral suppression, in turn, prevented new HIV infections and allowed people to live longer, healthier lives and that was how the world would eliminate HIV as a public health threat and end AIDS by 2030.

South Africa, Mashatile added, had made significant progress towards the targets. However, there was a struggle with the second 95, which was to initiate and maintain people on treatment. The country was currently sitting at 96-78-97. One of the first tasks the Minister of Health prioritised in the 7th Administration, was closing the gap in the second 95.

In October 2024, the Minister of Health announced an imminent launch of a campaign to find 1.1 million people who were infected with HIV but were not on treatment. The campaign was launched in February of this year at Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital and called “Close the Gap – Start and Stay on HIV Treatment”.

The campaign ran parallel to the “End TB Campaign” launched during the commemoration of World TB Day this year, with a target of testing five million people during the year 2025/2026 – thus leading to a substantial reduction in TB incidence and mortality in South Africa by 2035.

Mashatile said South Africa carried the highest HIV and TB burdens globally in relation to its population, with a higher prevalence among people aged 15 and 49. Adolescent girls and young women aged 15 to 24 record the highest new infections per week compared to all population groups.

To ensure data-driven strategies were aligned with the National Strategic Plan for HIV, TB and STIs, and global guidance, including the Global Prevention Coalition’s Ten Action Points, they needed to :

• Identify programme gaps and take remedial actions to scale up precision HIV prevention, including community-led and integrated approaches;

• Prioritise populations and regions most affected by the HIV epidemic.

• Address social, structural and legal barriers to HIV prevention.

• Promote the rapid adoption of new technologies and innovations.

• Strengthen leadership and accountability within HIV prevention efforts.

• Ensure real-time monitoring and data quality.

• Ensure the sustainability of, and adequate resource allocation for the HIV prevention response.

These initiatives resulted from coordinated efforts to not only achieve the UNAIDS objectives, but also to eradicate AIDS permanently in South Africa. Mashatile urged delegates to remember that behind all reports and statistics and behind every policy, there were real people – individuals with hopes and dreams, families and friends, each deserving of their compassion and commitment to their well-being.

‘’Let us use this conference as a platform to share our knowledge, our experiences and our best practices. Let us listen, learn and collaborate in ways that renew our resolve and inspire our actions. This conference provides an opportunity for all voices to be heard, especially from people at the frontlines. As government, we will not disregard these voices, and we are committed to enhancing our efforts to address the issues associated with the management of the three epidemics.

‘’We are a resilient country with a brilliant track record in HIV management. Together, we can shape a future where HIV/AIDS is no longer a threat, but a distant memory of our collective strength and determination’’.

Calls for SA to build sustainable HIV programmes

HEALTHCARE: Eight months since US funding was withdrawn, the government is urged to reduce reliance on donors and forge ahead with home-spun programmes…

By Ina Skosana

South Africa must be honest about the funding gap caused by U.S foreign aid cuts. The “golden age” of donor assistance, when there was an abundance of donor aid, is over.

“It’s decreasing not just for health, but for development broadly” is the stark warning issued by Professor Yogan Pillay, Director of HIV and TB research at the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

“This means the only way to do it is to increase domestic financing or change the way we do business,” says Pillay, speaking at the South African AIDS conference currently underway and ending today.

“Instead of looking backwards and how to find more money, we should be looking forward and changing the way we run the programme and the entire primary healthcare system,” says Pillay.

Prior to the US funding cuts, South Africa funded about 75% of its HIV programme. But, Dr Anna Grimsrud, a senior technical advisor at the International AIDS Society, argues that external funding still made a significant contribution, with PEPFAR providing R6.6 billion annually and the Global Fund R3.2 billion.

Eight months since funding was withdrawn, ‘South Africa must be honest about the funding gap caused by US foreign aid cuts’, she says.

“We must stop saying everything is fine. Admitting challenges is not conceding dependence; it’s owning the work ahead,” Grimsrud says.

The US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) supported 27 health districts in the country with a high HIV burden, providing services mainly to key populations at increased risk of HIV acquisition. Staff funded by PEPFAR included data capturers, nurses, lay counsellors, and pharmacist assistants. The withdrawal of funding brought all these programmes to an abrupt halt.

But activists say the government should have prepared for an eventual end to donor assistance.

“PEPFAR was here to support the government in some of the challenges that we had early in the days of HIV,” says Yvette Raphael, co-founder and co-director of Advocacy for Prevention of HIV and AIDS (APHA).

“However, some of our government officials and our government saw this as a way of evading their responsibility. And we are now here.”

Raphael, who has a long history of activism sparked by her own HIV diagnosis in the year 2000, argues that PEPFAR’s withdrawal from the country started years ago when the organisation stopped providing food parcels and other forms of support to people living with HIV.

“PEPFAR was never here to stay. Our government must now step up and close the gap.”

South African National AIDS Council (SANAC), CEO Dr Thembisile Xulu, agrees: “We all knew this day was coming.”

Xulu is the chairperson of the HIV leadership forum, which consists of the CEOs of the National AIDS Councils from over 40 countries. The collective has compiled a sustainability position paper where they reflect on how countries got so dependent on donor funding that the withdrawal jeopardises entire programmes.

“We collectively allowed donor funds to create systems outside of our own, leading to overlapping structures designed for donor requirements,” she says. Xulu adds that, as a country, South Africa has failed to leverage private sector capacity in the form of technology, innovations, and expertise to design a sustainable HIV programme.

These factors have left countries vulnerable as PEPFAR and other programmes reduce support.

What now?

Grimsrud stresses that time is essential to minimise the impact of funding withdrawal. “We cannot wait to make choices; waiting for stability is like waiting for a train that’s never coming.”

She says the country must identify components of HIV delivery that are essential to maintain, and figure out how to keep these services running more efficiently.

“We must build on our differentiated models of care, putting the people at the centre, supporting self-care, and using these models to drive integration and equity.” In addition, Grimsrud argues that the country’s budget must align with its commitments.

“We know that the National Department of Health has plans to expand HIV treatment coverage to seven million people as part of the 1.1 million campaign,” she states.

“But the budget we saw only supports a growth from 6 to 6.5 million people over the next three years. That gap between ambition and resources is exactly why prioritisation is so urgent.

“We need to plan realistically, cost honestly, protect what works, and innovate where efficiencies are possible.” – Health-e News