PRIORITY: Millions deprived of the right to essential services due to poor urban governance…

By Monk Nkomo

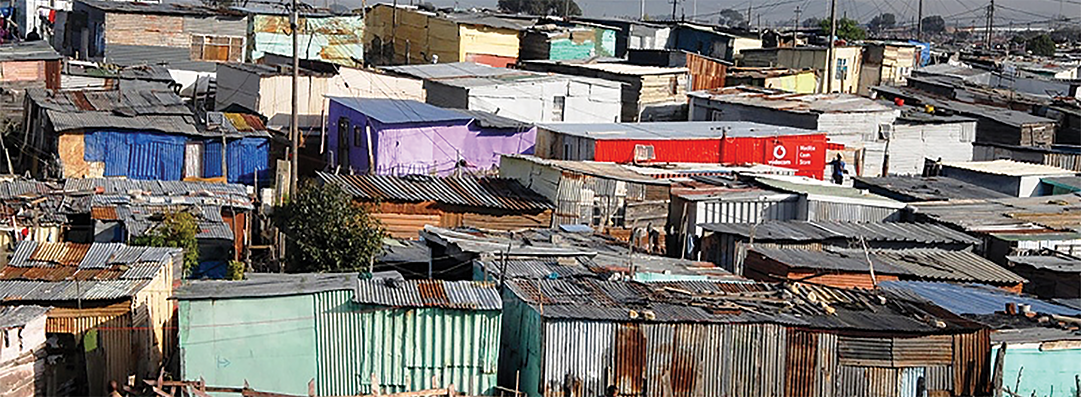

South Africa had a plethora of laws and policies on issues around access to housing and provision of essential services but millions of its people living in informal settlements were deprived of rights to these services due to neglect by central government.

This view is reflected by Amnesty International South Africa in their report : ‘’ Flooded and Forgotten – Informal Settlements and the Right to Housing.’’

The report documents the experiences of people living in informal settlements and other undeserved areas in South Africa. It is based on qualitative research carried out between February and September this year particularly in Johannesburg, eThekwini and Cape Town.

The report noted that the lack of access to adequate , well-located affordable housing was also due to under-resourced municipalities and poor urban governance. This had led to the growth of informal settlements in floodplains and low-lying areas which meant that people living there were increasingly impacted by flooding.

‘’ Despite South Africa having strong legislation and policy and clear international commitments as with so many other things in the country, implementation remains the issue.

The reality points to obvious failures of the government to adequately and thoroughly realise these obligations and this comes at a huge cost to the human rights, lives and livelihoods of millions of people’’, said Shenilla Mohamed, Executive Director of Amnesty International SA.

The government was putting the well-being and in many cases the lives of the more than five million people living in South Africa’s informal settlements, at risk by failing to provide them with access to quality housing and essential services, according to the report.

These people, many of them living on flood-prone land, were routinely left to cope on their own especially during severe weather conditions, despite the fact that the main responsibility for preparing for and responding to these disasters lay with the government.

“Informal settlements in South Africa along with other underserved areas like temporary relocation areas, are a sore reminder of the racial injustice and disenfranchisement that were hallmarks of the colonial and apartheid regimes preceding 1994.

‘’However, this does not mean that we must ignore the fact that the ongoing housing crisis and the failure of successive governments to guarantee the right to access to adequate housing among other human rights,” Mohamed said.

The government, she added, was failing the millions of people trapped in these underserved areas, especially at a time when economic hardships and poverty were rife.

People lived in informal settlements because there was a lack of affordable and accessible formal housing and sometimes because they were the only affordable means of living close to work or work opportunities.

The report noted that Article 10 of South Africa’s Constitution, which was part of the Bill of Rights, was clear that everyone had inherent dignity and the right to have their dignity respected and protected, no matter who they were.

Amnesty International SA called on the South African government to provide access to adequate housing to people living in the country and commit to upgrading informal settlements with access to essential services in a manner that complied with human rights law and standards, including through budgetary and policy commitments.

The government must also mobilise all the necessary human, financial and technical resources to ensure that disaster risk reduction was fully integrated into urban planning processes and these were implemented with a view to protecting residents of informal settlements from disasters and climate change and protecting their human rights.

The recent floods in June 2025 in the Eastern Cape province, which caused the death of over 100 people and washed away the homes of thousands of people, was a stark reminder that urgent and long-term action by the government was needed.

While South Africa’s Disaster Management Act and National Disaster Management Framework aimed to reduce the risk of disaster, there was ample evidence that not enough was being done towards this end.

Based on the experiences of people living in informal settlements documented in the report, interviews with experts and practitioners in the field and a review of reports, laws and policies, evidence showed that South Africa’s response to flooding disasters – whether major or seasonal– was patchy and piecemeal, with not enough done to prepare for such events, according to the report.

For example, people displaced by KwaZulu-Natal floods in 2022 were still in temporary emergency accommodation in poor conditions nearly three years later, indicating a lack of preparedness for recovery efforts.

Some of those displaced died after they were relocated to an area that was severely flooded in 2025, highlighting a serious failure to ensure that flood victims were relocated to safety. In the case of seasonal flooding, the support and assistance that many residents of informal settlements experienced was alarmingly poor or absent.

Although the KwaZulu-Natal Department of Human Settlements, in their response to Amnesty International, dated 30 October 2025, asserted that “informal settlements are not planned settlements and inherently their establishment would not be preceded by the availability of basic services”, South Africa remained bound by constitutional and international obligations to provide essential services to all residents, including those living in informal settlements.

The report also highlighted the human-induced climate change that had exacerbated the risks of flooding, already a seasonal problem in South Africa’s informal settlements and underserved areas. As elsewhere in the world, this meant that people who had contributed the least to climate change due to their low consumption patterns and were least able to cope with flooding were the worst affected by the impacts of climate change.

‘’One of the main concerns expressed to Amnesty International in all three metropolitan areas was that the regular seasonal flooding of informal settlements and underserved areas was rarely seen as warranting a disaster response by the municipalities.

The residents were simply left to fend for themselves and rely on charitable organisations’’.

South Africa, according to the report, had a plethora of laws and policies on issues around access to housing, provision of essential services such as water and sanitation, upgrading of informal settlements, a healthy environment and preparing for and responding to disasters.

It was also a state party to all the major international and regional human rights instruments including the UN International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights which guaranteed the rights to access adequate housing, water and sanitation.