ICON: From Actonville to global stages, Pops Mohamed blended tradition, futurism, and faith—leaving behind a musical archive as luminous as the spirit he carried…

By Atiyyah Khan

The supermoon shone radiantly on December 4 —the night Pops Mohamed died at the age of 75. Our neighbourhood in the East Rand was in darkness due to a power outage, yet the sky glowed brilliantly, as though illuminated by the noor (light) of Mohamed’s spirit.

A musician, composer, poet, sound healer and producer, Mohamed was a South African cultural giant. Over 50 years, he released 20 albums and performed alongside iconic musicians, moving with ease through Western, Eastern and African sound worlds. Humility and gentleness defined him, and on the morning of his janaazah (funeral), that peace filled the air.

Born Ismail Mohamed-Jan in Actonville in 1949, music came to him early. “Music? It just came to me,” he told me three weeks before his passing.

After discovering the piano at school, he fell in love with the guitar at 14. His parents sent him to Dorkay House—the beating heart of Johannesburg’s arts scene—where he trained under German teacher Gilbert Strauss. He later took piano lessons at FUBA, studying under Rashid Lanie and Denzil Weale.

When the Group Areas Act reshaped the East Rand, his family was forced to move from Actonville to Reiger Park. During his teens and twenties, he played in pop bands such as Les Valiants, The Dynamics and El Gringo’s while working day jobs, including a 14-year stint at the steel company Dorman Long.

A chance encounter with a talent scout led him to Kohinoor Records in Johannesburg, run by Rashid Vally of As-Shams/The Sun. Mohamed brought along a cassette demo, which impressed Vally enough to arrange studio time.

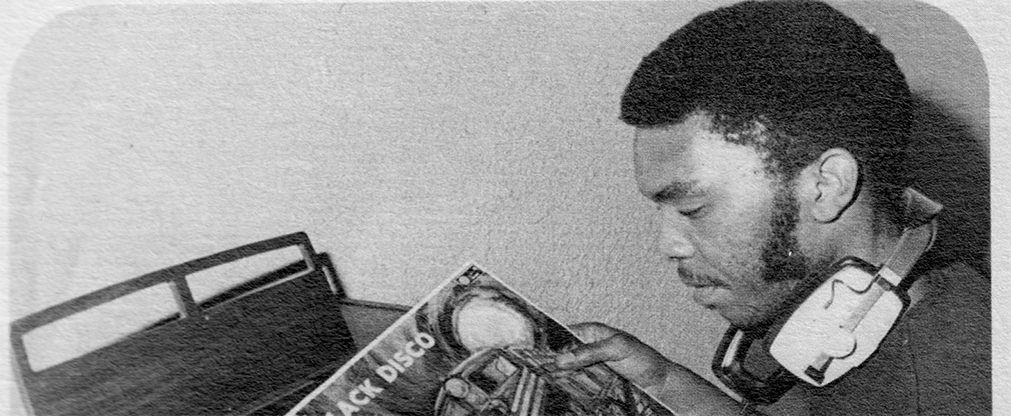

There he met Basil “Manenberg” Coetzee and Sipho Gumede, with whom he recorded the seminal Black Disco album in 1975—an Afro-soul, funk and jazz fusion classic. Two follow-ups followed, forming a trilogy that became symbolic resistance under apartheid. “Black Disco was our way of saying, ‘we are with you,’” Mohamed explained.

The success of Black Disco paved the way for Movement in the City, featuring Robbie Jansen and drummers Monty Weber and Gilbert Matthews. The group released two albums—Movement in the City (1979) and Black Teardrops (1981)—with a third issued posthumously.

After leaving the factory, Mohamed committed to music full-time and worked at Kohinoor, where Vally groomed his ear for jazz. Fridays at the tiny shop on Kort Street were a swirl of fish-and-chips lunches, crowds of music lovers and rich storytelling. This period shaped Mohamed profoundly. “That was the highlight of my career,” he said. “That’s where it all started.”

His next leap came when Swiss producer Robert Trunz of Melt2000 heard his cassette and tracked him down at Kohinoor. Trunz invited Mohamed to join his new label in England and to help recruit South African talent. After consulting Vally—who encouraged him to go—Mohamed moved abroad.

At Melt2000, he worked closely with musicians such as Moses Molelekwa, Busi Mhlongo, Amapondo, Sipho Gumede and Madala Kunene.

Self-taught and endlessly curious, Mohamed fell in love with sound engineering. Studio time was expensive, so he trained himself, reading manuals and observing engineers.

He soon produced his own albums and videos, and later founded his labels. His discography grew to include the award-winning Ancestral Healing and multiple Kalamazoo volumes, named after a once-vibrant multiracial settlement near Reiger Park destroyed under apartheid. His track “Kort Street Bump Jive” honoured the bustling street outside Kohinoor.

A pan-Africanist and fierce experimenter, Mohamed called himself a “Futurist.” He wove together ancestral sounds of the Khoi, San and West Africa with influences from the East. His instrumental mastery was vast—mbira, kora, uhadi, umrhube, mouth bow, didgeridoo, berimbau, keyboard, organ and guitar. His work often reflected politics, spirituality, unity and healing.

Deeply spiritual, Mohamed practised Islam with devotion. His connection to faith was quiet but unwavering. During our final interview, he paused mid-conversation to honour the Athaan from our local mosque—a gesture reflecting his mindfulness and respect.

Just before the COVID-19 pandemic, he moved back to Actonville to live with his daughter Yasmeen. Though he fell gravely ill in 2021, he recovered enough to perform again. In 2023, he received the South African Music Awards Lifetime Achievement Award.

Tributes poured in after his passing. Lawyer and storyteller Nkazimulo Qaaim Moyeni reflected on how Mohamed held his spirituality and music together as one: “The drum, the kora, the uhadi and the umrhube were not merely instruments to him; they were gifts… tools that opened doors to frequencies older than memory.”

Friend Ayhan Cetin described him as “one of the unseen pillars of society,” while pianist Rashid Lanie recalled Mohamed’s relentless curiosity and his “scholar’s heart,” noting how quickly he turned new knowledge into creative innovation.

In the final months of his life, Mohamed was excited about remastering Kalamazoo Vol. 5, released digitally shortly before his death. On the same day, As-Shams issued the long-awaited archival release of Movement in the City 3.

At his core, Pops Mohamed remained rooted in faith, family and the pursuit of knowledge. His gentle nature and musical brilliance reflected a lightness of spirit that touched countless lives. He leaves behind an extraordinary archive—one that will continue to illuminate listeners for generations. – Africa is a Country

• Atiyyah Khan is a South African arts journalist, researcher and DJ based in Cape Town. His article has been shortened.