GOVERNANCE: Once a symbol of sacrifice and popular struggle, the ANC now confronts a crisis of elitism, assimilation, and substitutionism, argues journalist and political commentator Ido Lekota. As money politics hollow out its liberation ethos, only radical internal democracy can prevent irreversible decline…

By Ido Lekota

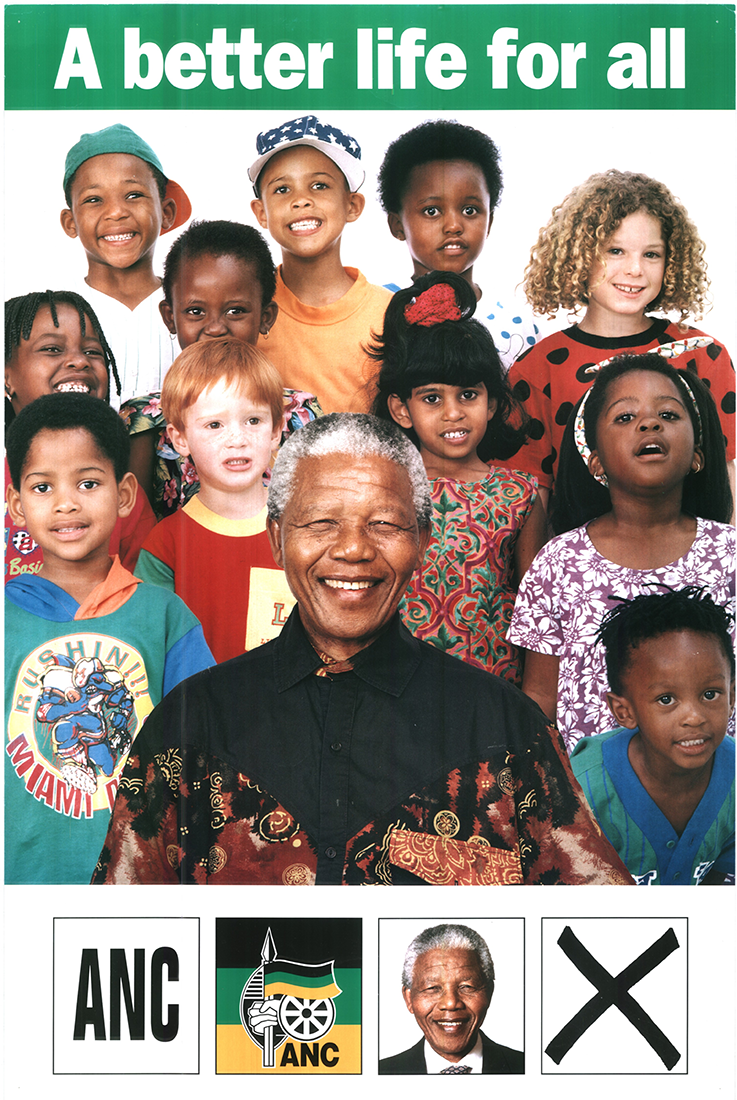

Once revered as one of the world’s most successful liberation movements, South Africa’s African National Congress (ANC) now finds itself trapped in a paradox of its own making.

Having defeated apartheid and assumed state power, the movement has struggled to reconcile its liberation identity with the realities of long-term governance.

The result is a deepening crisis—one rooted in elitism, political assimilation, and a vanguardist culture that substitutes elite priorities for popular will.

At its recent National General Council, ANC leaders publicly acknowledged the corrosive impact of “money politics” and conspicuous wealth among senior figures. These admissions, while notable, rang hollow. They followed years in which public trust eroded as party elites accumulated vast personal fortunes amid mass unemployment, failing services, and deepening inequality. The language of renewal has become ritualistic, disconnected from lived reality.

Elitism is now one of the ANC’s defining features. Once associated with sacrifice, exile, and imprisonment, senior party office is today often linked to luxury vehicles, private estates, and corporate directorships.

These displays are routinely defended as evidence of post-apartheid success, yet they stand in stark contradiction to the movement’s founding values. The ANC’s own Integrity Commission has warned that such excesses undermine its moral authority, reinforcing perceptions of a political aristocracy detached from the poor majority.

This elite formation was not accidental. Post-1994 empowerment strategies—most notably Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) and cadre deployment—were designed to redress apartheid’s racial exclusions.

Instead, they helped create a politically connected capitalist class dependent on state patronage. Public contracts and procurement systems became mechanisms for political reward, producing a layer of “tenderpreneurs” while hollowing out state capacity.

South Africa now ranks among the most unequal societies in the world, with over half the population living in poverty while a small elite captures the overwhelming share of national income.

Elitism is reinforced by assimilation: the fusion of liberation movement and governing party into a single, self-protecting political ecosystem. Like many post-colonial movements, the ANC entered government with a hierarchical, centralised organisational culture forged in exile and underground struggle.

Once in power, this translated into a paternalistic governance model, where leaders positioned themselves as custodians of a historic mission rather than accountable public servants.

This assimilation deepened during the late 1990s as South Africa adopted market-oriented reforms that diluted the redistributive ambitions of the post-apartheid settlement. The party-state boundary blurred, with deployment committees controlling access to public office and state-owned enterprises. Political loyalty increasingly trumped competence, enabling corruption and weakening institutions.

In this context, the ANC shifted from being an agent of transformation to a defender of an unequal status quo—often responding defensively, rather than decisively, to social crises such as the 2012 Marikana massacre.

At the core of this degeneration lies substitutionism: a vanguardist logic in which party elites claim to embody the will of the people, even as they override popular demands. Internal democracy has been steadily eroded by slate politics, vote-buying, and factional patronage. Policy decisions—such as regressive levies and infrastructure tolls—have frequently been imposed despite widespread public opposition.

This pattern is not unique to South Africa. Across the post-colonial world, former liberation movements—from Zimbabwe’s ZANU-PF to Mozambique’s FRELIMO—have followed similar trajectories, where revolutionary legitimacy is used to justify elite dominance and political closure.

In South Africa, substitutionism also demobilised vibrant civil society traditions that once anchored popular participation. Trade unions were co-opted, critical voices marginalised, and participatory forums reduced to technocratic rituals.

The political consequences are now stark. The ANC’s electoral dominance has steadily declined, forcing it into fragile coalition arrangements and exposing its organisational decay. Youth unemployment remains among the highest globally, feeding social unrest, xenophobic violence, and political alienation. Surveys show collapsing trust in political institutions and dwindling belief in the ANC as an ethical leader.The implications extend beyond party politics.

Economically, South Africa has experienced prolonged de-industrialisation and chronic skills shortages, exacerbated by corruption in training institutions.

Politically, fragmentation within the historic tripartite alliance mirrors the unravelling of liberation coalitions elsewhere in southern Africa. Into this vacuum step populist movements that channel legitimate anger but risk reproducing the same authoritarian vanguardism they oppose.

Reversing this trajectory requires structural, not rhetorical, reform. Internally, the ANC would need to dismantle elite capture by instituting transparent, verifiable internal elections, enforcing binding lifestyle audits, and ending patronage-based deployment. Public office should be tied to merit, community accountability, and recall mechanisms.

At the systemic level, stronger regulation of political finance is essential to curb donor influence and money politics. Electoral reform that strengthens constituency accountability could reconnect representatives to voters rather than party lists. Revitalising labour politics and civil society autonomy is equally critical to rebuilding countervailing power.

Ultimately, renewal demands more than organisational fixes. It requires a renewed commitment to material redistribution—through land reform, industrial policy, universal basic services, and inclusive growth strategies that place social justice ahead of elite accumulation.

History suggests that liberation movements can renew themselves—but only when they abandon the myth of moral entitlement and embrace democratic accountability.

For the ANC, the choice is stark: evolve into a genuinely accountable political party, or continue along a path of decline that risks surrendering its historic legacy to irrelevance. Liberation, after all, is not a permanent status—it must be continually earned.

*Ido Lekota is an independent veteran journalist and political commentator