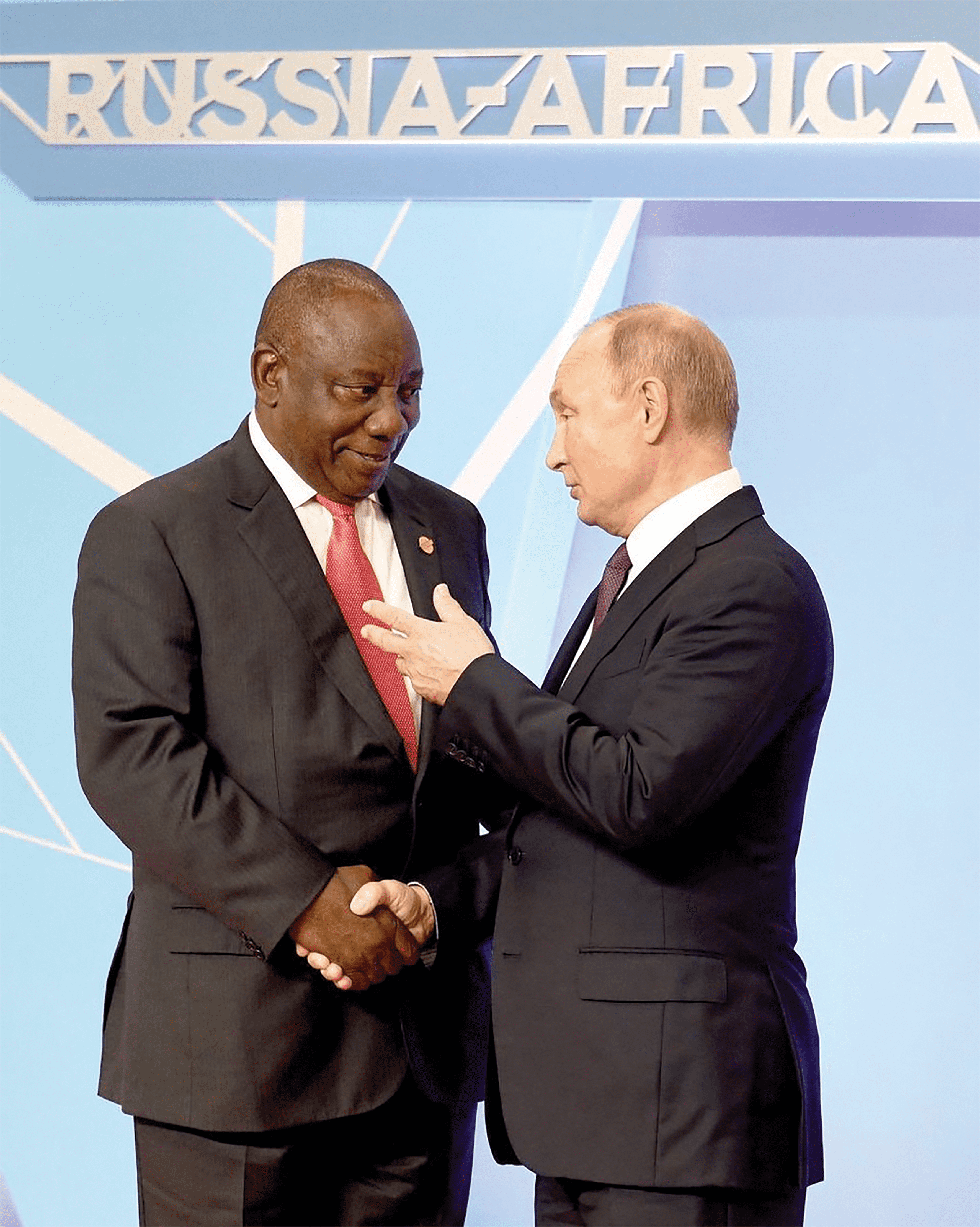

DILEMMA: In less than 24 hours, the South African authorities announced their intention to withdraw from the International Criminal Court (ICC) before declaring it a misunderstanding. South Africa is due to receive Vladimir Putin in August, while the Russian President is facing charges at the ICC. South African lawyer Howard Varney analyses what is fuelling this tension within the ruling party in Pretoria and what it may mean for the ICC.

By Thierry Cruvellier

JUSTICE INFO: On April 25, President Cyril Ramaphosa announced at a press conference that the African National Congress (ANC), the party in power in South Africa since 1994, has asked that the country withdraws from the International Criminal Court (ICC). Then a bit later there was an about turn and the government said it wasn’t what they meant. How do we explain this?

HOWARD VARNEY: Well, I would love to be a fly on the wall when those discussions happened. Someone can only speculate because people outside of the [ANC] party and certainly outside of the National Executive Committee don’t really know. But what I can tell you is that there is quite a strong feeling amongst people in the ANC that it is time to withdraw from the ICC. And as you will recall, this is nothing new. If we rewind and go back to 2016-2017, around the visit of then President Al Bashir [of Sudan] to the African Union Heads of State summit in Johannesburg, the whole issue was sent and fronted. At that point, you recall that there was litigation, and court orders against government. They ignored those court orders. They allowed Bashir to leave in a very underhand manner, and then thereafter they proceeded to or they attempted at least to withdraw, making an executive decision which in turn was struck down by the courts. The court said, you can’t just sign a decree, you’ve got to go through parliament.

They then came up with a bill which was put before parliament. That bill remained bubbling in parliament for several years, until just in the last few months the ANC eventually said they’re not going to withdraw, but rather to work within the ICC, and also to push for the Malabo Protocol [that gives criminal jurisdiction to the African Court of Justice and Human Rights] to be ratified by enough countries so that local criminal justice solutions could be pursued.

So, what changed recently, did the anti ICC forces within ANC feel stronger?

I think the only thing that can explain it or precipitated that announcement was the dilemma that South Africa is facing with the upcoming visit of Vladimir Putin, who’s one of the members of the BRICS states. So there is a BRICS Head of State summit due to take place in Durban in August. And many in the ANC simply cannot bring themselves to execute a warrant of arrest against the President of Russia while he’s attending a glamorous event. That’s a step too far for them.

But then a withdrawal now would not change the dilemma over the visit of Putin, because there is a one-year delay before a withdrawal from the ICC is effective. Absolutely. That clause is applicable. So, we’re bound by it.

And do you think they didn’t see that?

There probably many within the party who are not legally aware of the finer details and who don’t know about it. But, certainly, the lawyers within the ANC would know that you can announce anything you like right now, your obligations will remain in place for a whole year. And until then, you’ve got to comply with everything the ICC asks you to do. And, unless the ICC withdraws the arrest warrant or cancels those charges, South Africa is duty-bound to effect that arrest. And I can tell you that the same organisations that went to court previously are busy preparing to [the challenge] and we may very well be faced with another constitutional crisis in a matter of weeks.

Do you see any difference between the situation in 2016 and today’s? Or is it exactly the same set of tensions and legal obstacles?

I suspect those in the ANC would argue that many of the issues that were being discussed back in 2016 are still relevant today. Back then, there was the big peace versus justice debate, and that slavishly sticking with the ICC would interfere with South Africa’s ability to negotiate peace deals and be a peace broker. That’s not the big issue right now, although I have little doubt that it’ll be raised again. Right now, the big issue is South Africa’s obligation under the act to affect the arrest. And many in the ANC now see membership of the Rome Statute as interfering with their ability to conduct international diplomacy, which, in turn conflicts with a decision of the party that South Africa had played quite a central role in developing the Rome Statute and setting up the International Criminal Court. Throughout the 1990s, South Africa was one of the driving forces [behind the ICC]. It had the strong support from people such as Nelson Mandela. And, indeed, at the time, for example, Mandela was the lead peace broker in Burundi. And he’s actually on record as saying that he sees no conflict between pursuing those peace negotiations and pursuing justice through the ICC. Within the party, they’ve taken a decision that it’s time to reform the ICC from within, but that historically it wouldn’t be a good idea to withdraw. And then suddenly this happened, and that has thrown the cat amongst the pigeons.

What do you expect to happen in August?

Well, it’s anybody’s guess right now. I think there are some within Foreign Affairs that are really hoping that Putin is going to say, look, I’m managing a war right now, I’m quite tied up, I will join for one or two sessions via Zoom, and that would, of course, resolve everything. Postponing the meeting, holding it somewhere else, that would all be convenient for South Africa. If none of that happens and everybody digs in their heels and he does come, then that will usher in yet another constitutional crisis. Because the courts have already said in the Bashir case that we are duty bound to effect the arrest. And actually, prior to that, it’s quite likely that some civil society organizations will be approaching the courts on an urgent basis and seeking what’s called a declaration so that a question will be posed to the courts dealing with not an academic matter, but a real life one and the courts will rule yet again that the state is obliged to effect the arrest. And if that happens and the president and government decide to ignore the ruling of the courts, then that will be fundamentally problematic for our constitutional order. There have been examples of government departments ignoring court orders, but eventually they do comply. But where you have the President himself saying to the constitutional court, ‘I will not obey that particular order’, then that is a complete betrayal of what we fought against during the apartheid days.

We were at one point a leading nation in the fight for human rights. We can’t really be regarded as that anymore, given various positions that the government has taken. But up until this time, we’ve always been seen as a constitutional dispensation that respects the rule of law. So, it will be more than just a bag of hot potatoes.

Behind the tension exposed by the government’s contradictory statements there’s a much more global defiance where the ICC is seen as a tool of the West applying double standards in their prosecutions. Do you feel that matters a lot in South Africa and that South Africans just want to make a point that it’s not acceptable?

It certainly is a big issue, and I think it’s one of the factors driving policy on this matter. There is strong sentiment in South Africa, more particularly within the ANC and left-leaning political groupings, that there is a certain double standard when it comes to global justice, and with some justification. Personally, I think it was correct that an indictment was issued against Putin. But, then if one looks at the role of the West in a country like Iraq and the role that President Bush and Prime Minister Blair played in it, one would have thought that they should have been investigated as well, and if necessary, indicted. But needless to say, that never happened. So that’s a clear double standard. And yes, one shouldn’t really be getting into a ‘what aboutism’ type argument, but certainly on the streets here, that is a big sentiment. And, certainly within the ANC, I would say that is probably the dominant sentiment. One must always remember that it was the Soviet Union, not the West, that were the primary backers of the armed struggle in South Africa. They were the ones providing weapons and training. The West wasn’t doing so. So, there is a lot of loyalty that remains with Russia. Yes, of course, today Russia is not the Soviet Union and the ideologies are fundamentally different. But nonetheless, that sentimentality is still there. So there is a strong anti West approach that is discernible.

And as a result, do you feel Ukraine has increased that tension and that sentiment?

Yes, I think it has. A lot of people would normally be vigorously opposed to any country invading and violating the sovereignty of another country. One sees all kinds of sophisticated type arguments being put up to try and justify the invasion, which under any other circumstance, they would never have done so. But because of the history and because of that sentiment, you do see these arguments, which in my view, have little merit being pursued.

Do you expect South Africa to eventually withdraw from the ICC at this point?

I think it would be very difficult for South Africa to withdraw at this stage. There was a moment where they had that bill before Parliament, and that was the moment. To restart that whole program would be exceedingly difficult and would take several years. So I don’t see South Africa withdrawing anytime soon. When people realize that even if you do withdraw now, it’s not going to affect what happens in August and whatever happens in the next year, they will see the futility of it.

And how do you see the incident this week affecting the ICC itself?

It is undermining and unsettling for the ICC to have, you know, one of the states’ parties that were so central to its birth and creation, engaging in this kind of flip flop approach. So, yes, it doesn’t help the ICC in this regard. Then again, unfortunately, we were once seen as something of the gold standard on questions such as justice and international affairs and diplomacy. We’re hardly that anymore. We’re no longer seen as a country that is a beacon of hope and human rights. I don’t think we are taken as seriously as we once were. And it may be that those in the ICC simply dismiss this as the bickerings of a bunch of lightweights. As an average South African, I certainly hope that everybody sees the light of day and that Vladimir Putin doesn’t fly to Durban in August, because if he does, it is going to be seriously disruptive to the South African state and the norms that we have been trying to establish since democracy in 1994.

- This article was sourced from Justice Info is an independent media outlet published in French and English covering justice initiatives in countries dealing with serious violence. It is run by Fondation Hirondelle, based in Lausanne, Switzerland, financed by its readers and by public and private donors. Howard Varney is a practising advocate at the Johannesburg Bar. He is a Senior Programme Adviser at the International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ). In the early 1990s, he was an attorney with the Legal Resources Centre in Durban where he represented victims of political violence in public interest litigation, judicial inquests, and commissions of inquiry. He worked with the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission. He was also the Chief Investigator for the Sierra Leone Truth and Reconciliation Commission. He continues to represent victims of past conflicts in the courts of South Africa to vindicate their rights. Varney has a BA LLB from Natal University and an LLM from Columbia Law

Published on the 97th Edition