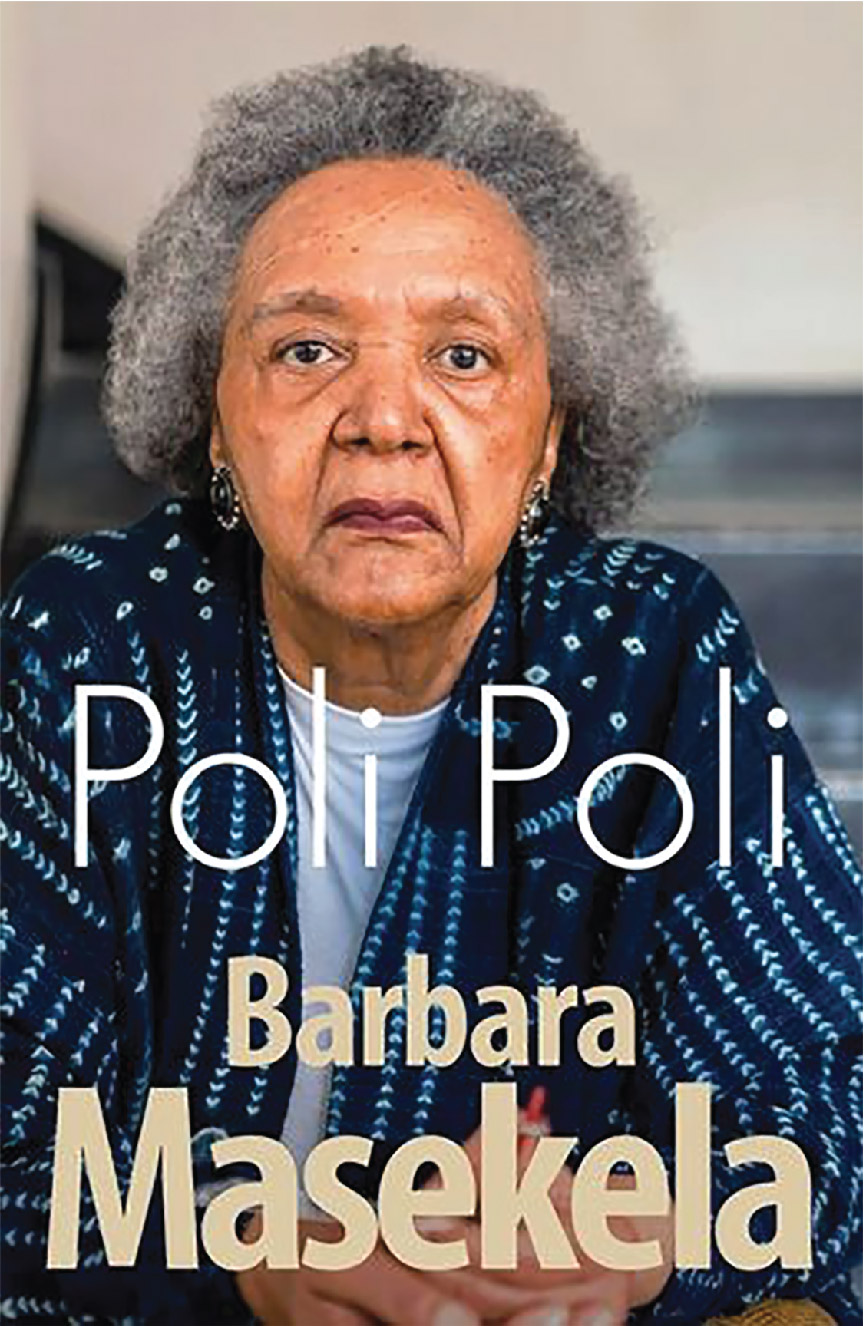

DRACONIAN: The profundity of Poli Poli lies, not only in the brilliant prose, but in how it centres Black women – often relegated to footnotes of history books – in stories of resistance…

Reviewed by Malaika Wa Azania

The story of colonial conquest and imperial devastation is often told in the language of macro impacts – in the amount of land violently dispossessed, the number of the colonised shipped across the Atlantic Ocean to work as slaves in the plantations of the Americas, and in the statistics of the brutally maimed and murdered.

This is also true of the story of apartheid in South Africa – a story often told about draconian laws that stripped Black people of their humanness, of the massacres that claimed the lives of the unnamed, and of the heroes, mostly men, who went to prison for decades or led the liberation movements from underground.

Very rarely is the story of colonialism and of apartheid told as a story of families – ordinary men and women who experienced the brutalities of forced removals, pass laws and existence in a zone of non-being.

Apartheid is described as a system that affected many, and yet, there is minimal intentional engagement with the geo-histories of these nameless and faceless people – these families who were forced to exist and resist under conditions transmitted from centuries before.

In Poli Poli, Barbara Masekela tells the story of colonial imposition and apartheid barbarity that centres the lives of ordinary people. She tells the story of men and women in the coal mining community of KwaGuqa, the Place of Kneeling, who had arrived carrying their meagre belongings and with tears steaming down their forlorn faces, having been forcefully removed from yonder distant lands they had once called home. De-agrarianised and dispossessed, they had made their way to this place where

Masekela would begin the journey of her life in the home of her grandmother, Ouma Johanna Mabena Bower, the central figure in this story of survival, sacrifice and belonging. Ouma, seen through the eyes of a young Barbara in a constant state of evolution, is a towering figure in a way that history does not allow Black women to be.

Proud and somewhat stoic, she raises her grandchildren in a home where, though not overtly displayed, love lives. Like many women in KwaGuqa and across the country, she raises her grandchildren in order that their parents may work or study in faraway cities to provide a materially better life.

Though Masekela’s parents undoubtedly love her and her brother Minkie (the iconic Hugh Masekela), they make difficult choices imposed on them by a system that is brutal on the Black family structure. The consequence is the orphanhood that would define the life of Masekela even when, in the 1950s, she would eventually move to the sprawling township of Alexandra to live with them.

It is in Alexandra where Masekela is introduced to the brutality of the apartheid system on urban life in South Africa. There, in the belly of deprivation, she is forced to surrender a part of herself in order that she may be accepted into a school that is reserved only for so-called Coloured children. This confrontation with racial classification is an assault not only on her identity, but patriarchal traditions that insist that children belong to their father’s people.

Her father’s response to what he deems an affront on his manhood reflects the anguish of many Black men under apartheid: being stripped naked, figuratively and literally, and denied the things that define, in a traditional sense, manhood. Expressions of emasculation litter the story, sometimes presenting as bravado.

is especially pronounced in young men like Ntambo, a feared criminal who would forcefully and violently attempt to have a relationship with Masekela. In an environment like Alexandra where Black men were animalised and dehumanised, this aggression was inevitable, and women were the easier target because they were already rendered infants by the apartheid regime.

But while Poli Poli is a story about life under colonialism and apartheid for Black people, who in many ways were natives of nowhere, it is fundamentally a story about Black women. In Ouma Johanna, we meet a Black woman whose life was radical. It may not seem so by today’s standards, but for a Black woman to raise and educate her children on her own, under a system that insisted on Black people being nothing more than hewers of wood and drawers of water, was an act of defiance.

Ouma Johanna’s creative traditional beer brewing enterprise was also a radical act of defiance – refusal allow the system’s destruction of businesses owned by Black women who were unwilling to sell their labour to White-owned factories or be indentured labour on their farms. But her radicalism is also expressed in her silences – and in the sacrifices she makes on her knees in order that her children and grandchildren may live on their feet. Though apartheid takes a lot from Ouma Johanna, including her home, her daughter lost in part to the migrant-labour system, and her only son Khalo, who is brutally murdered by racist youth to whom killing Black people is sport, she insists on surviving. She insists on waking up each morning to hold the Masekela family together. I cannot think of anything more radical.

The profundity of Poli Poli lies not only in the brilliant prose with which the story is told, but in the ways it centres Black women who are often nothing more than footnotes in history books and in stories of resistance. The myth of the African as unthinking has been cemented by centuries of colonial literature and the pseudo-sciences of eugenics. And while it is true for all peoples of the continent that we have been rendered unthinking, and that Black people continue to be diminished to a permanent state of childhood, it is especially so for Black women.

Those who have benefitted greatly from the erasure of Black women, and from laying claims to our intellectual labour that exists in multiple sources whose contributions have been expropriated and appropriated, argue that this epistemic violence is the result of Black women being voiceless. Such is nothing more than a convenient explanation for this injustice, for in the profound words of Indian author and activist, Arundhati Roy:

“There is really no such thing as the voiceless. There are only the deliberately silenced, or the preferably unheard”. In Poli Poli, Masekela insists on the deliberately silenced and ignored being heard and seen. With gentleness, she unlocks even the complexities of Ouma Johanna and the many women in her life whose existence is not easy but who refuse still, to die.

She paints a confronting picture of what Black people lost under apartheid beyond the land and economy. We lost families, identities and the innocence of childhood. Masekela also lost her citizenship – a decision she made when she took an exit permit out of the country of her birth, to newly independent Ghana that represented everything colonised people were fighting for across the continent, and which would take South Africa many decades to achieve, at a cost so high it has not been sufficiently calculated.

Poli Poli demands to be read, if not for anything else, to honour the many Black women to whom we owe this democracy, but whose names and faces we may never fully know. It must be read for our grandmothers who suffered and sacrificed, and for our mothers who, like Sis Pannie, Masekela’s mother, even with chains of patriarchy and oppressions of culture, served our country and fought for our right to be human.

*Wa Azania is the bestselling author of Memoirs of a Born Free: Reflections on the Rainbow Nation and Corridors of Death: The Struggle to Exist in Historically White Institutions