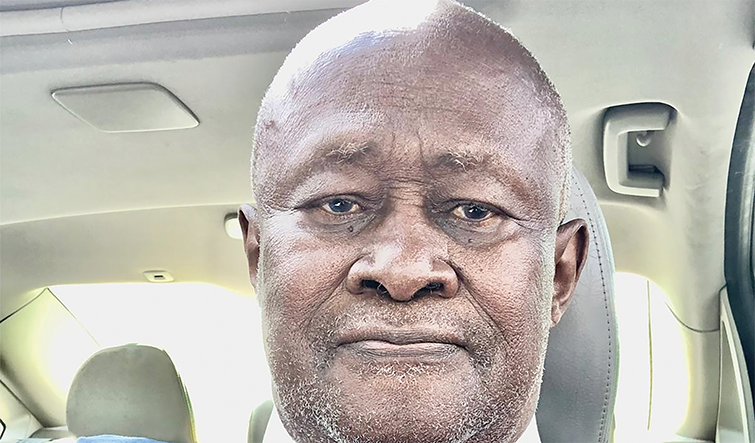

SURVIVOR: Following a successful kidney transplant bio chemist and drug manufacturer Kunu Matima is now an organ donor campaigner

By Ali Mphaki

God and my ancestors have not given me a break in this life, laments Lekunutu Matima.

With a slight quiver, the Dube, Soweto-born Matima, better known as Kunu, details his lifelong struggles as we speak via a WhatsApp call the other day.

*My life has been one helluva struggle after another. In fact, I’m lucky to be alive,” he says, drawing a long, slow breath.

Indeed, if life has been unkind to Kunu, with man-made hurdles placed along his way, his life journey is also a triumph over adversity

Exiled from South Africa after the June 16, 1976 students uprising, it turned out his coming to America would reveal a more violent and sinister form of racism than the one he was accustomed to in apartheid South Africa. It was like to flying from a frying pan into the fire,

To delve into Kunu’s tumultuous life journey, we should perhaps start way back in 1972 when he was said to have failed the then exclusive Joint Matriculation Board examination.

In fact, as reported in The Weekend World newspaper dated February 4. 1973, not a single Sowelo student had obtained a first-class pass when the results were announced in December 1972.

An aggrieved Kunu, a pupil at the iconic Morris Isaacson High School at the time, did not believe he had failed and took the matter up, applying for the remarking of his exam papers.

He paid R30 for the remarking. Lo and behold, it turned out Kunu had passed with flying colours, earning five distinctions, including in Biology and in English, which saw him want to enrol for a medical degree at Wits.

Kunu says he had satisfied all the requirements, including his own funding to study at Wits University only to be told by the late Dean of faculty Professor Errol Tobias that the Security Branch, a unit of the erstwhile South African Police, had ordered him to reject Kunu’s application because he was a “Communist troublemaker”.

Whilst he was not deterred in his quest to continue his studies and subsequently enrolling for a Science degree at Turfloop university, to this day he still wonders how many futures of gifted and ambitious students were destroyed in this manner.

At Turf, he would be confronted with another challenge. The apartheid security branch would approach Kunu to spy against his fellow students or risk being failed.

Not one to be a snitch, Kunu approached the newspapers, and his story received good coverage exposing the underhand tactics of the apartheid machinery.

Hounded by the security police Kunu decided to skip the South Africa and landed in the United States, where he continued his studies to become a Biomedical and Pharmaceutical scientist, a drug developer, author and a US Civil Rights expert.

Armed with his qualifications, he joined one of the biggest drug companies in the US, Wyeth-Ayerst, in 1989, where he produced many beneficial drugs and was never given credit for them.

Bringing a sour taste to the mouth is that his less contributing colleagues, who were white, received pay increases and promotions for his work.

Not one unfazed by challenges, Kunu took up the matter with the courts fighting against one of the biggest drug companies in the world.

In court papers, Kunu says he was systematically watched, humiliated, and harassed at the company. The decade-long court battle ended in 2001, when Kunu lost his bid for compensation for racial bias.

A US District Court jury, however, found in 1997, that Wyeth-Averst had retaliated for Kunu’s complaint. It awarded no damages. I don’t understand. However, something Kunu thinks is an injustice

. It was while he was engaged in his court battle that his house on Newall Street had its post-box blown sky high by plastic explosives.

His daughter had a few weeks prior received threatening calls, and Kunu thinks the acts were in retaliation to his court battles with the drug company. Spokesman for the company Doug Petkus would not comment on the case.

As if it were not enough, Kunu would fave serious health challenges in 2020 and in desperate need for a kidney transplant. Last year on mother’s day Kunu received a kidney transplant after four-and- half years of being in life-saving dialysis and also having his prostate treated at the same time.

Speaking after his successful treatment, Kunu was enormously grateful, proclaiming his life has changed. ‘No more dialysis, and I’m looking forward to a better life once my healing is complete,’ he says, urging New Yorkers and everybody else to start donating organs like eyes, kidneys, etc .to save lives.

Without a doubt, he misses South Africa badly, and among his major regrets is that his “old friends” from Turfloop, among them president Cyril Ramaphosa, never supported his idea of starting his own SA-based pharmaceutical company in 1998.

What feels like a stab in the back is that 52 years of trying to save lives with his drug inventions, there’s been no honour for him from his native South Africa.