CHRONIC: Giant step forward to help treat foot ulcers and cancerous tumours that affect millions as technology offers alternative to antibiotics…

By WSAM Correspondent

A team of international scientists has developed a more effective treatment for chronic wounds, bringing hoping to millions of diabetics on chronic treatment worldwide for foot ulcers and internal wounds.

More than 540 million people worldwide are living with diabetes, of which 30 percent develop a foot ulcer during their lifetime. The cost of managing chronic wounds such as diabetic foot ulcers already exceeds $US17 (R323) billion annually and this cost is expected to climb in coming decades as obesity and lack of exercise lead to more cases.

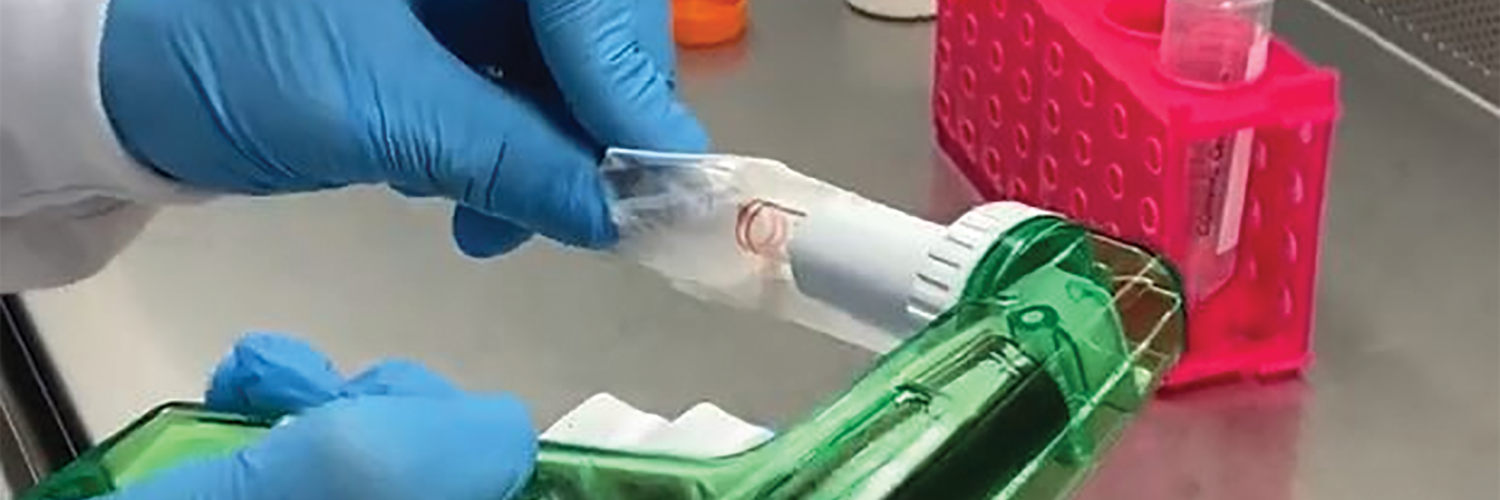

The treatment, which is part of a University of South Australia (uniSA) study, involves using an ionised gas called plasma instead of antibiotics or silver-based dressings to treat chronic wounds. It involves boosting the plasma activation of hydrogel dressings with a unique mix of different chemical oxidants that decontaminate and help heal chronic wounds.

The university’s physicist, Dr Endre Szili, who led the study published this week in Advanced Functional Materials, describes the new method as “a significant breakthrough” that could revolutionise the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers, internal wounds and potentially cancerous tumours. “Antibiotics and silver dressings are commonly used to treat chronic wounds, but both have drawbacks,” Szili says. “Growing resistance to antibiotics is a global challenge and there are also major concerns over silver-induced toxicity. In Europe, silver dressings are being phased out for this reason.”

The benefits of cold plasma ionised gas have already been proven in clinical trials, showing it controls not only infections, but also stimulates healing. This is due to the potent chemical cocktail of oxidants, namely reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (RONS) it produces when it mixes and activates the oxygen and nitrogen molecules in the ambient air.

Szili and his colleagues have shown that plasma activating hydrogel dressings with RONS make the gel far more powerful, killing common bacteria.

Although diabetic foot ulcers were the focus of this study, the technology could be applied to all chronic wounds and internal infections. “Despite recent encouraging results in the use of plasma activated hydrogel therapy (PAHT), we faced the challenge of loading hydrogels with sufficient concentrations of RONS required for clinical use. We have overcome this hurdle by employing a new electrochemical method that enhances the hydrogel activation.”

As well as killing common bacteria (E. coli and P. aeruginosa) that cause wounds to become infected, the researchers say that the plasma activated hydrogels might also help trigger the body’s immune system, which can help fight infections. “Chronic wound infections are a silent pandemic threatening to become a global healthcare crisis,” Szili says. “It is imperative that we find alternative treatments to antibiotics and silver dressings because when these treatments don’t work, amputations often occur.”

“A major advantage of our PAHT technology is that it can be used for treating all wounds. It is an environmentally safe treatment that uses the natural components in air and water to make its active ingredients, which degrade to non-toxic and biocompatible components.”

Szili says that, in future, plasma could be used to treat cancerous tumours by activating drugs contained within gels injected into the body.

“The active ingredients could be delivered over a lengthy period, improving treatment, with a better chance of penetrating a tumour. “Plasma has massive potential in the medical world, and this is just the tip of the iceberg,” Szili says.

The next step would be to involve clinical trials to optimise the electrochemical technology for treatment in human patients.

Psoriasis and Ethnic Diversity

GENETIC: The condition might be underdiagnosed in African populations because of differences in healthcare access, underreporting, or even misdiagnosis…

By Ahmed El Hofy

Psoriasis, a chronic skin condition affecting millions worldwide, has long been a topic of concern in the medical community, in that no cure has been discovered, although there are various options available to lessen its symptoms.

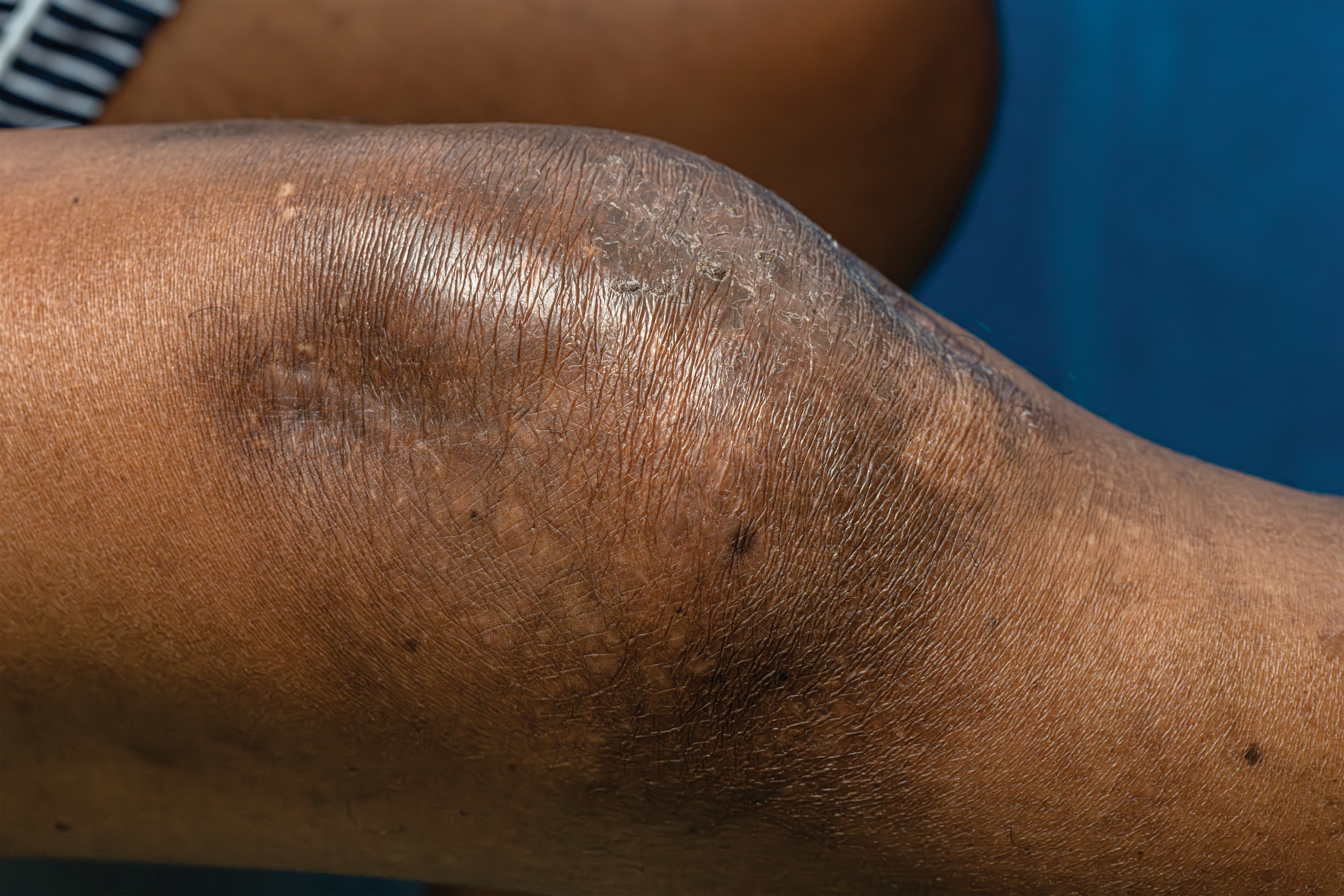

Characterised by hardened skin and itchy, scaly patches, psoriasis is a result of the immune system mistakenly attacking healthy skin cells. While the exact cause remains elusive, researchers have delved into the intriguing interplay between genetics, environment and ethnicity. There have also been studies undertaken as to disparities in its prevalence and severity among different racial and ethnic groups.

Characterised by hardened skin and itchy, scaly patches, psoriasis is a result of the immune system mistakenly attacking healthy skin cells. While the exact cause remains elusive, researchers have delved into the intriguing interplay between genetics, environment and ethnicity. There have also been studies undertaken as to disparities in its prevalence and severity among different racial and ethnic groups.

The bottom line is that psoriasis knows no boundaries – it can affect anyone, regardless of race or ethnicity. Research does suggest, however, that certain ethnic groups might be more susceptible to this condition than others.

Historically, psoriasis has been considered to be less common in people of African, Hispanic, and Native American descent, in comparison to Caucasians. Psoriasis appears to be most common in the northern countries of Europe, with Norway topping the list. East Asia appears to have the lowest incidence.

However, it’s essential to note that these trends can change over time because of various factors, such as lifestyle changes, environmental factors, and genetic interactions.

More recent studies are suggesting that psoriasis might be underdiagnosed in African populations because of differences in healthcare access, underreporting, or even misdiagnosis, in lower income districts. Additionally, the genetic diversity within Africa is vast, so the umbrella term of “African” is not a precise one, when it comes to the accurate reporting of genetic difference. Healthcare professionals and researchers continue to investigate in a more focused fashion, in the quest to provide better insights into the condition’s prevalence among different populations.

The reasons behind the ethnic disparities between psoriasis patients are complex and multifaceted. Genetic predisposition does indeed play a significant role, with specific genetic markers associated with psoriasis having been identified in different population groupings. For instance, variations in the HLA-C gene have been linked to a higher risk of psoriasis in Caucasians, whereas genetic factors such as the PSORS1 locus have been found to be more prevalent among individuals of South Asian descent.

The reasons behind the ethnic disparities between psoriasis patients are complex and multifaceted. Genetic predisposition does indeed play a significant role, with specific genetic markers associated with psoriasis having been identified in different population groupings. For instance, variations in the HLA-C gene have been linked to a higher risk of psoriasis in Caucasians, whereas genetic factors such as the PSORS1 locus have been found to be more prevalent among individuals of South Asian descent.

And then environmental factors have also been reported to exacerbate these genetic predispositions. Climate, lifestyle, and socioeconomic status all contribute to the intricate web of psoriasis susceptibility. Studies have shown, for example, that psoriasis cases rise in colder, less sunny regions.

This is possibly the result of reduced exposure to sunlight; a natural source of vitamin D, which plays a role in skin health. Lifestyle factors such as smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, and stress have also been linked to the onset and severity of psoriasis. These factors are often allied to one’s cultural environment.

Limited access to healthcare, education, and resources, particularly among marginalised communities, can lead to delayed or mistaken diagnoses, and therefore the inadequate management of symptoms. Addressing these disparities requires a holistic approach that combines medical intervention, education, and awareness campaigns that are specifically tailored to different ethnic groups.

Raising awareness about psoriasis is a crucial first step, and culturally sensitive educational initiatives can debunk myths and misconceptions, thus encouraging affected individuals to seek medical help without fear of social stigma.

Furthermore, both governmental and private medical bodies should encourage research that focuses on understanding the unique genetic and environmental factors contributing to psoriasis within different population groupings. By adopting this more specific and targeted approach, scientists will hopefully get closer to developing therapies that are tailored to – and therefore more effective for – populations of specific genetic profiles. This way, outcomes can be improved for patients across diverse populations.

In the quest for equality in healthcare, it is imperative that we acknowledge and address the disparities in psoriasis prevalence and severity among different ethnic groups. By fostering a collaborative environment that includes healthcare professionals, researchers, policy makers, and communities, we can bridge the gap in psoriasis care.

Together, we can ensure that no individual falls outside of the metaphorical radar, and everyone, regardless of ethnicity, receives the support and treatment that he or she requires to manage this chronic condition effectively.

- Ahmed El Hofy is general manager of South Africa for The Janssen Pharmaceutical companies of Johnson & Johnson