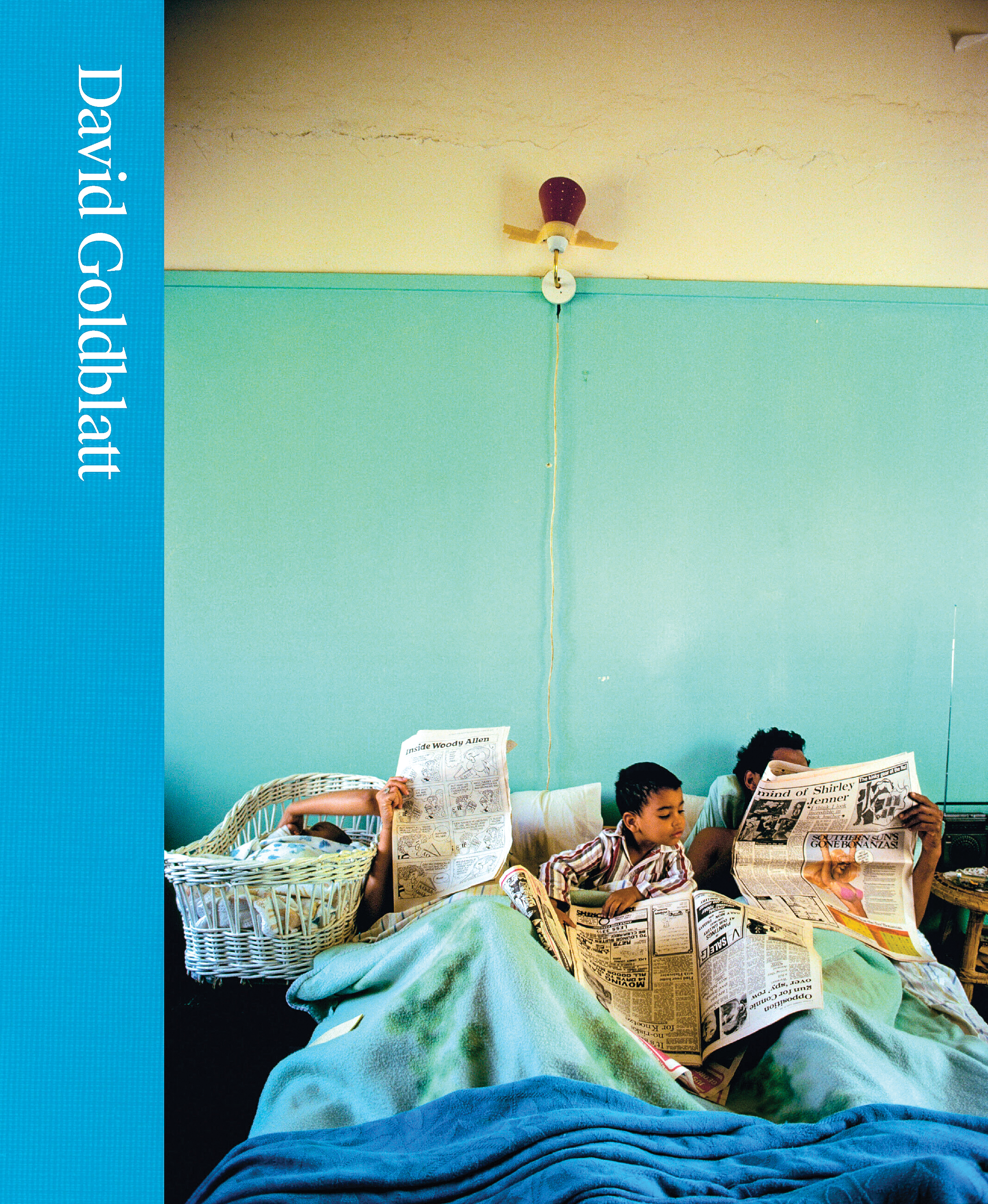

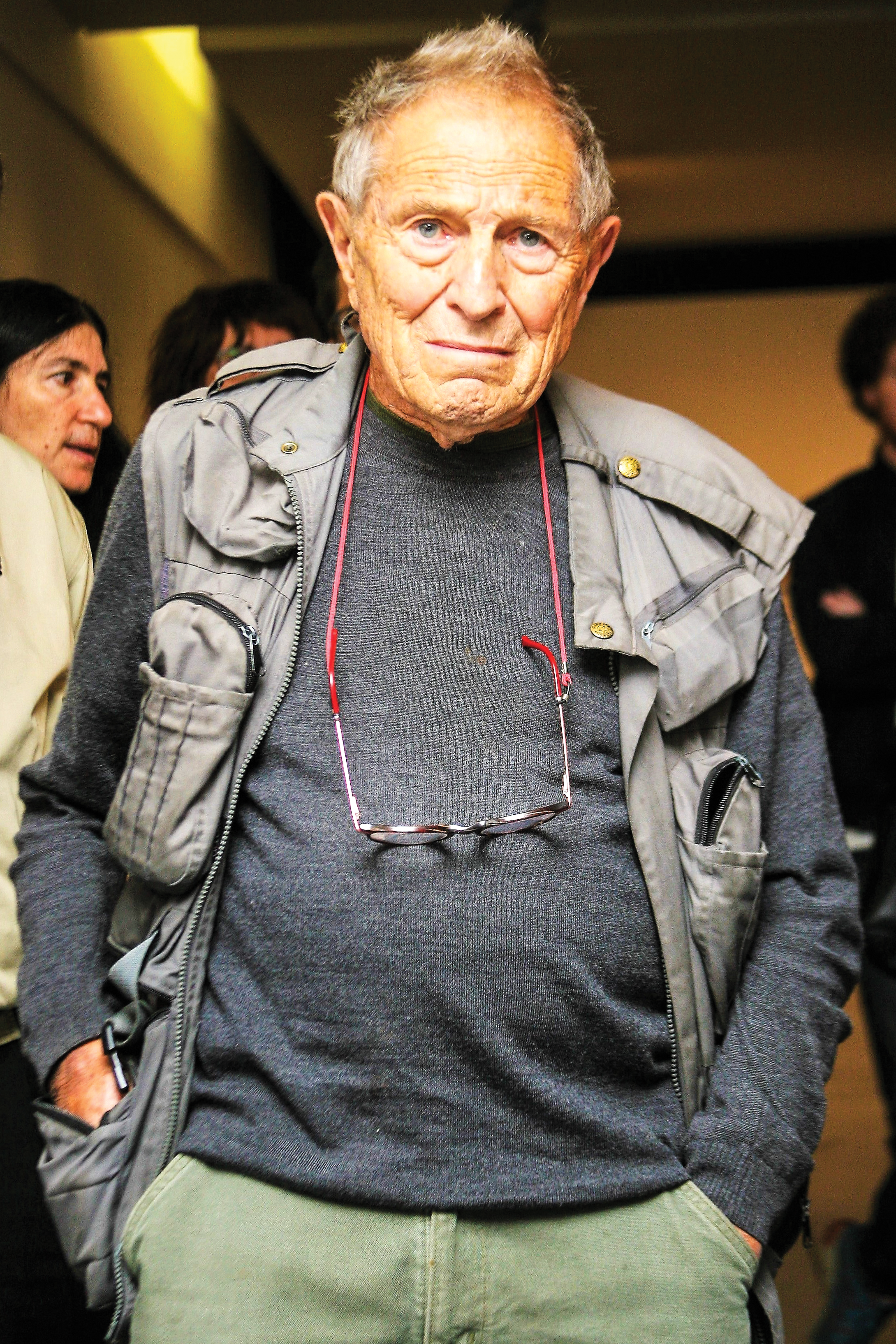

PORTRAIT: A catalogue of the veteran lensman’s long life in photography while documenting a variety of human life throughout the length and breadth of South Africa…

By Jacob Mawela

The title to the late South African photographer David Goldblatt’s new tome emanates from his inventiveness to venture out to document white life in its private and cocooned place.

To this end, the veteran lensman did the unusual to place a classified advert in the Sunday Times newspaper between the years 1971 and 1975 – for whites in Joburg’s northern suburbs to volunteer to pose for portraits for his cameras. The note – typed on a simple plain white page and headlined “Free Photography” – was brief and read in part: There is no catch and no ulterior motive.

Alas, notwithstanding the extent of his pledge, he couldn’t immediately bait willing sitters for the portraits he had in mind!

“. . . the lack of response from White middle-class people,” the Randfontein-born lensman mused to a newspaper back then, “is their pathological horror of exposing themselves emotionally, visually or verbally – a lapse they equate with sleaze ‘tell-all’ interviews in the Sunday papers.”

“. . . the lack of response from White middle-class people,” the Randfontein-born lensman mused to a newspaper back then, “is their pathological horror of exposing themselves emotionally, visually or verbally – a lapse they equate with sleaze ‘tell-all’ interviews in the Sunday papers.”

That unrequited foray pending apartheid-era South Africa was probably an exception rather than a norm when those familiar with the Hasselblad Foundation International Award and Henri Cartier-Bresson Award-recipient’s seven decades long oeuvre consider its reach and totality in documenting his native country’s various races, colours, tribes and cultures!

With regards to Black South Africa, his inquiry appeared to have been tolerated even though he initially hesitated to venture into strutting his exploration within the country’s bastion of the darker demographic, namely Soweto.

Such a juncture was presented to him back in the late 1960s when a magazine approached him with the view of undertaking a project in the sprawling metropolis – with Goldblatt suggesting that Black photographer Peter Magubane be the one who should rather execute the task.

Yet, that was not to be interpreted as ducking the assignment on his part, for, if anything, came the advent of the 70s – he was to wholly dedicate his being with the documenting of the hardscrabble location alongside poet Sipho Sepamla.

The dichotomy between White reluctance and Black consent to the photographer’s foray into their world is peradventure cast into proper perspective by South African intellectual Breyten Breytenbach in his description of white South Africa as ‘vulture culture’ and the apartheid system as “providing the artificially created distance necessary to attenuate, for the practitioners, the very raw reality of racial, economic, social and cultural discrimination and exploitation”.

It was this fissure when a reader peruses through the 280-page hardcover collector’s item, rendered visually evident in the form of imagery spanning from 1948 – incidentally at the commencement of legislated segregation – to 2017, pending which Goldblatt was to consistently focus his camera lenses into the lives and conditions of the opposite demographics.

SOUTH AFRICA’S CHEQUERED HISTORY THROUGH THE LENS

Included in the mostly monochromatic presentation are aspects of his now familiar series, viz, The Transported of KwaNdebele (a documentary on Black labourers who daily commute betwixt the homeland and the city of Pretoria for work), On the Mines (imagery depicting on goings at Anglo-American Corporation operated mines), In Boksburg (a visual record of a middle-class White community) and Some Afrikaners Photographed (his ambivalent insight into the lives of South African Afrikaners).

Comprising a masterful layout with complementing bold-font text ascribed to diverse contributors, the offering includes gelatin silver prints made by Goldblatt himself, as well as carbon ink and pigmented inkjet prints produced under his supervision by Tony Meintjes – a long-time colleague of his.

Covering a whole range of societal pursuits, landmarks and landscapes – the compilation straddles both apartheid-era and the post-apartheid period, in an incredible attestation of the photographer’s longevity and dedication to his craft! Goldblatt, it is worth mentioning, consciously opted to dedicate his being to documentary photography (and the laissez faire approach it accorded him) over the more conventional photojournalism that most practitioners choose out of necessity than passion!

In the book’s preface, academic, Njabulo S Ndebele, aptly encapsulated the following regarding the lensman’s oeuvre: “Goldblatt’s quiet, yet persistent photographic search for ‘a new future’ in South Africa, led him wherever its people congregated to find mutual inspiration, consolation in mourning, relaxation and entertainment, or their daily bread. He went to their communities and homes; their churches, mosques, temples, and other sacred spaces; and the factories, farms, and mines where they worked. His reach over the years of his long life in photography was extensive both geographically, stretching across South Africa, and in the variety of human situations he so carefully observed through his lens.”

To corroborate Ndebele’s acquaintance with David’s quest, the book is bound to both enthral and invoke contemplation of the viewer with images ranging from a 1955 one captioned Wait-a-Minute Photographer depicting an African man all resplendent in his best wardrobe daintily posing for a sidewalk photographer utilising one of the large vintage box camera (the one in which the snapper had to stick his head under a black sack in order to gain clarity of what appears on the viewfinder); a 1972 one depicting the butchering of a coal merchant’s horse for its meat (shades of ‘Majapere’, the stereotyping inference to horsemeat consumers) in Tladi, Soweto – to those documenting the last days before the destruction of the Asian neighbourhood of Fietas under the contrite Group Areas Act and those evidencing the still existing migrant labour system-induced norm of workers from latter day Mpumalanga-Limpopo provinces (erstwhile KwaNdebele homeland) who have to commute daily on Putco buses along the accident-prone Moloto Road, to-and-from their Pretoria workplaces!

A section titled, Dialogues, features some works of fellow South African photographers, viz, Ernest Cole, Santu Mofokeng, Zanele Muholi, Seopedi Motau, Lebohang Kganye, Jo Ractliffe and Sabelo Mlangeni – with some of the afore-mentioned contributing text reflecting on some of Goldblatt’s images.

The first posthumous monograph on him, the presentation has been four years under construction, with the content gleaned from the Art Institute of Chicago, the Yale University Art Gallery and the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University.

- David Goldblatt: No Ulterior Motive is published by Yale University Press and distributed across South Africa by Jonathan Ball Publishers. It is available at leading bookstores countrywide for approximately R1 500