PILLAR: Reverred as a tried-and-tested wordsmith, an all-rounder, a passionate and dedicated gatekeeper of the craft…

By Joe Thloloe

For years, thousands of the readers of the newspaper Sowetan, then the biggest circulation daily newspaper in the country, received, saw and benefitted from the work of Ike, but they never got to know him and acknowledge it. As a subeditor, he was one of the anonymous pillars of the publication.

A Sam Nzima, for example, shoots a picture of Hector Petersen being carried to the journalists’ car after the police had shot him and the picture, with Sam’s by-line, is printed in the newspaper and is reproduced around the world: the readers remember Nzima and the reporters who told the story in words. The sub-editors, the people who designed the pages, who meticulously ensured that the language used by the journalists met the style of the publication and told the story well, who chose the pictures to go with it, remain in the shadows. The readers don’t know them, unless they are as flamboyant and imaginative as a Dave Hazelhurst.

Ike chose to be one of those shadowy figures, a subeditor, a guardian of the country’s journalism.

Paying tribute to Ike, one of the giants of black journalism, Mothobi Mutloatse, now a renowned book publisher, said: “I salute Rre Segola for having transitioned to that area most journalists feared – even to this date – that is subbing, in his mature years well into retirement. Robala ka Kagiso mogaecho.”

I’d argue that journalists don’t fear that part of the newsroom – it is the limelight and the fame inherent in other parts of the craft that keep them out.

I first met Ike when he joined us at the Rock, Orlando High School, in the 1950s. He and a friend Cosmo Nkonyeni, brother of songstress Ruth Nkonyeni, used to travel to school in Orlando East from Crown Mines in the then centre of Johannesburg.

We became a three-some, hammered into shape by the dedicated teachers who gave us more than what the architects of Bantu Education had planned – the Kambules, the Makhubalos, the Harveys, the Kanandas, the Mkhwanazis, and others, men and women who infused us with a love of reading and writing. The Rock prepared us for the lives of storytelling that became our love. You just need a roster of us who ended up in newsrooms, starting from Mecro Zwane right up to Diago, Thami Mazwai and me.

At the lunch break, we walked across the main road to Sizanani Store to buy fatcakes, polony and fatcakes – yes, magwenya.

I used to tease him as The only Spaniard in Soweto, because his Setswana name, Diago, sounded like Diego, Maradonna’s first name. Portuguese and Spanish was maar die selfde.

And the last time I spoke to him was when he and fifty other journalists I had bumped into in my long career descended on my home in Roodepoort because they had heard I wasn’t well.

He didn’t complain about his pains and aches: we always assume that these are “normal” at our age. We chatted about our old friend, Cosmo, who relocated to Swaziland during our difficult years.

Another stalwart, Mathatha Tsedu, reminded about 60 of us old journalists who chat regularly in a WhatsApp group: “Yoh, Bra Ike! The subbing supremo but more importantly, the one, with Zingisa’s mum, who were left holding the Mwasa (Media Workers Association of South Africa) baby when many of us were banned. I remember coming out of detention and rocking up at the Khotso House…to find Bra Ike there. He organised a flight ticket to Polokwane and some spending money from the SACC…

“When we did Joe’s gig a few weeks ago, he was unsure if his health would allow. He came because he was at heart a man of organisation, of belonging, and he wasn’t going to miss meeting all of us…. Little did we realise that it was his farewell to all of us. Peace, abuti.”

The breadth and depth of the journalists who doffed their hats and saluted Diago on the WhatsApp group is an indicator of his contribution to the story of our country – I know I’m inviting criticism from those I may omit – Moegsien Williams, Thami Mazwai, Khangale Makhado, Mokgadi Pela, Khulu Sibiya, Nomvula Ralo, Mothobi Mutloatse, Zubeida Jaffer, Isaac Moroe, Mathatha Tsedu, Oupa Ngwenya, Pearl Luthuli, Musa Zondi, Siphiwe Mhlambi, Maud Motanyane, Phil Mthimkhulu, Jovial Rantao, Mike Siluma, Barney Mthombothi, Sekola Sello, Bokwe Mafuna, Zingisa Mkhuma, Amina Frense, Rich Mkhondo, Khathu Mamaila, Phil Molefe, Pule Molebeledi, Subry Govender, Mpikeleni Duma, Shalotay, Latiefa Mobara, Sandile Memela, Mothobi Mutloatse, Sam Mathe, Willie Bokala, Rashid Seria, Chiara Carter, Collin Nxumalo, Ido Lekota , Mzimkhulu Malunga – an army that carries the story of South African journalism and our country in their veins.

Diago, you are a giant and we feel your weight as you transition to the world of our ancestors. Lala ka Kagiso. Ramasedi a thobe dipelo tsa bana le losika la Segola lotlhe.

By Jo-Mangaliso Mdhlela

Today you see your friend and former colleague in seemingly good health, then in the morning you are told he has left this life to join eternity.

How do we deal with this disappointment?

This is how Joe Thloloe, a veteran journalist, editor, ex-trade unionist, press Ombudsman, Havard University Nieman Fellow, said of his long-time friend, journalism colleague, and Orlando High schoolmate, Ike Diago Segola, following the news of his death. Obviously, I have reconstructed Thloloe’s words, without distorting their meaning, to suit my tribute to Segola, the one I loved dearly.

To join eternity is conceptually to enter an endless state of life, timeless, or beyond the limitations of mortal life. Death is final, yet it holds a title of being enigmatic, a human puzzle or wonderment of wishing to cling to our physiological existence, hoping it never ends, yet like all other things, life has its own limitations, one of which is death.

Thloloe reminded me, as we commiserated, reflecting on Segola’s death, and the sadness each of us felt about it, that his other name was Diago.

Diago?

The name Diago, a Spanish name, carries religious connotations. It is associated with the biblical character of St James, one of Christ’s followers, who was said to be dedicated to teaching, missionary zeal, and a patron saint of those who suffered an assortment of ailments, including arthritis.

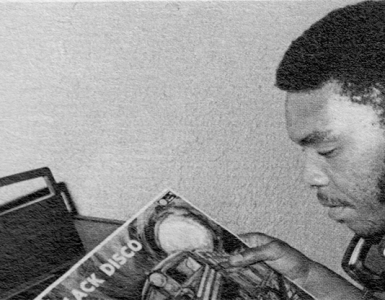

Was Segola that kind of person, caring for others, and dedicated to teaching and informing others through journalism? Sure, he was a communicator, a journalist of many years, more than 60 years in the craft, a wordsmith of great note, who first marked his presence in the world of journalism at the now defunct Rand Daily Mail from the 1960s.

I first met him at the Sowetan in the 1980s. Segola was amiable, friendly, good-natured, knowledgeable, but uneasy about the political climate of the time, as he was, as senior sub-editor, about bad copy produced by reporters. He could be seen pacing the newsroom, screaming at the top of his voice, rebuking against badly written copy.

As he was uneasy about a badly written copy, he did not take kindly to oppressive politics of the time. He also understood the aberration of political injustice was equally prevalent in the working environment of journalists and media workers.

We may ask, what would he do about it?

He rolled up his sleeves, signed up as a member of the trade union, the Media Workers Association of South Africa (Mwasa), thus joining the working class in the fight against injustice at the workplace.

This would be reflected many times when Segola joined the union picket lines, carrying a placard, toyi-toying in unison with struggling masses, for the restoration of social and political justice for a black people. Yes, for many years Segola formed part of the collective to fight against workplace injustices inflicted on black employees by oppressive bosses.