INNOVATION: Artificial Intelligence tool will allow doctors to analyse surgically removed tumours more accurately and in real-time…

By WSAM Correspondent

CHAPEL HILL, North Carolina – Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning tools have received a lot of attention recently, with the majority of discussions focusing on proper use. However, this technology has a wide range of practical applications, from predicting natural disasters to addressing racial inequalities and now, assisting in cancer surgery.

A new clinical and research partnership between the University of North Carolina (UNC) Department of Surgery, the Joint UNC-NCSU Department of Biomedical Engineering, and the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Centre has created an AI model that can predict whether or not cancerous tissue has been fully removed from the body during breast cancer surgery. Their findings were published in Annals of Surgical Oncology.

“Some cancers you can feel and see, but we can’t see microscopic cancer cells that may be present at the edge of the tissue removed. Other cancers are completely microscopic,” said senior researcher Dr Kristalyn Gallagher, section chief of breast surgery in the Division of Surgical Oncology and UNC Lineberger member. “This AI tool would allow us to more accurately analyse tumours removed surgically in real-time, and increase the chance that all of the cancer cells are removed during the surgery. This would prevent the need to bring patients back for a second or third surgery.”

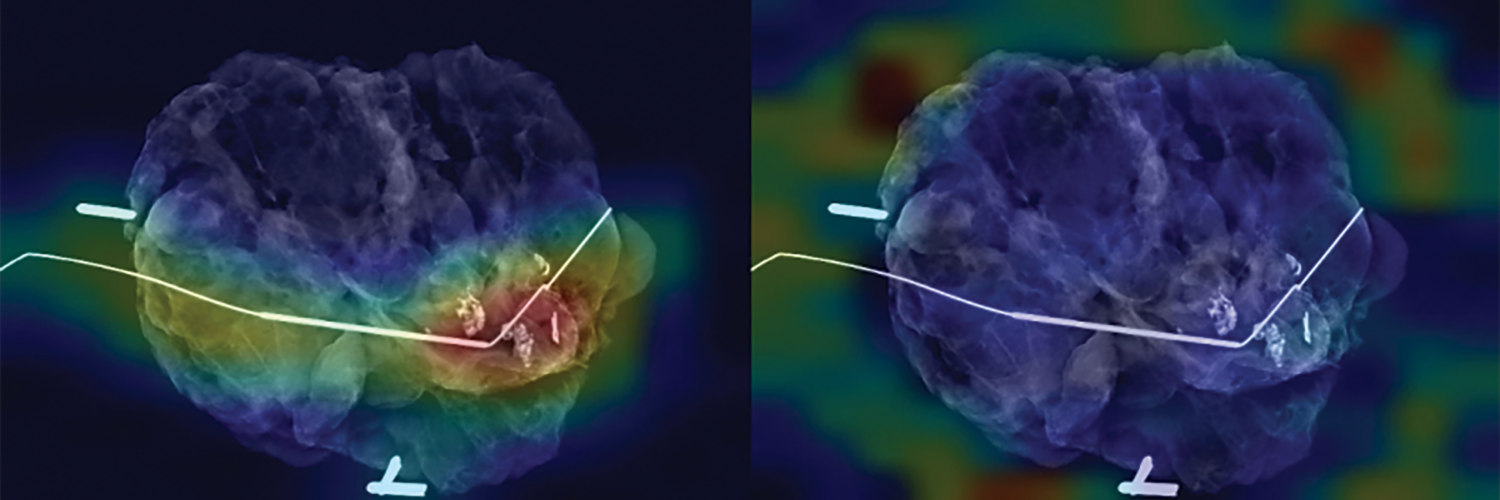

During surgery, the surgeon will re-sect the tumour (also referred to as a specimen) and take a small amount of surrounding healthy tissue in an attempt to remove all of the cancer in the breast. The specimen is then photographed using a mammography machine and reviewed by the team to make sure the area of abnormality was removed. It is then sent to pathology for further analysis.

The pathologist can determine whether cancer cells extend to the specimen’s outer edge, or pathological margin. If cancer cells are present on the edge of the tissue removed, there is a chance that additional cancer cells still remain in the breast. The surgeon might have to perform additional surgery to remove additional tissue to ensure the cancer has been completely removed. However, this can take up to a week after surgery to process fully, while specimen mammography, or photographing the specimen with an X-ray, can be done immediately in the operating room.

To “teach” their AI model what positive and negative margins look like, researchers used hundreds of these specimen mammogram images, matched with the final specimen reports from pathologists. To help their model, the researchers also gathered demographic data from patients, such as age, race, tumour type, and tumour size.

After calculating the model’s accuracy in predicting pathologic margins, researchers compared that data to the typical accuracy of human interpretation and discovered that the AI model performed as well as humans, if not better.

“It is interesting to think about how AI models can support doctor’s and surgeon’s decision making in the operating room using computer vision,” said first author Kevin Chen, MD, general surgery resident in the Department of Surgery. “We found that the AI model matched or slightly surpassed humans in identifying positive margins.”

According to Gallagher, the model can be especially helpful in discerning margins in patients that have higher breast density. On mammograms, higher density breast tissue and tumours appear as a bright white colour, making it difficult to discern where the cancer ends and the healthy breast tissue begins.

Similar models could also be especially helpful for hospitals with fewer resources, which may not have the specialist surgeons, radiologists, or pathologists on hand to make a quick, informed decision in the operating room.

“It is like putting an extra layer of support in hospitals that maybe wouldn’t have that expertise readily available,” said Shawn Gomez, an engineer and professor of biomedical engineering and pharmacology and co-senior researcher on the paper.

“Instead of having to make a best guess, surgeons could have the support of a model trained on hundreds or thousands of images and get immediate feedback on their surgery to make a more informed decision.”

Since the model was still in its early stages, researchers would keep adding more pictures taken by more patients and different surgeons. The model would need to be validated in further studies before it can be used clinically.

Researchers anticipate that the accuracy of their models will increase over time as they learn more about the appearance of normal tissue, tumours, and margins.

TACKLING COVID’S LONG-TERM EFFECTS

ENERGY: Can creatine supplements help people with long COVID?

By Bobby Berman

Dietary creatine may improve the fatigue associated with long COVID and other symptoms, according to a small new study. Creatine—nowadays often used as a workout supplement—plays an important role in helping cells produce and use energy throughout the body.

Participants given creatine for six months after reporting long COVID symptoms showed improvements in fatigue, body aches, loss of taste, breathing problems, and concentration issues that often follow SARS-CoV-2 infection, compared to others given a placebo. Among the often-mystifying, extended effects of COVID-19 is post-viral fatigue syndrome, or (PVFS). A small new study finds that dietary creatine may help alleviate its symptoms.

Getting more creatine through diet could help alleviate chronic fatigue after long COVID, according to research The study found that taking dietary creatine for three months substantially improved feelings of fatigue, and by six months, had produced improvements in body aches, breathing issues, loss of taste, headaches, and problems concentrating — or “brain fog” — compared to people given a placebo.

Long COVID is also associated with a bewildering range of other symptoms as well, including sleep problems, dizziness, chest pain, depression, and anxiety. People with post-viral fatigue syndrome or (PVFS) may be unable to perform activities they had no trouble performing before COVID-19. They may also have unsatisfying sleep and bounce back after exertion only with difficulty.

The study, conducted in Germany, tracked the effect of creatine on 12 people ages 18 to 65 who had confirmed COVID-19 in the previous three months.

Each participant had at least one lingering post-COVID symptom, such as breathing problems, loss of their sense of smell or taste, pain in their lungs, head or body aches, and issues with concentrating.

Half of the participants received four grams of dietary creatine daily. The dietary creatine was in the form of Creavitalis. The remaining six participants received an equivalent amount of a placebo, inulin. Creavitalis is a food ingredient manufactured by Alzchem GmbH, who provided funding for the research, along with the Provincial Secretariat for Higher Education and Scientific Research in Trostberg, Germany. The study is published in Food Science and Nutrition.

What is creatine?

Creatine occurs naturally in the human body, where, said Professor Andrew R. Lloyd, infectious disease physician and director of the University of New South Wales (UNSW) Fatigue Clinic and Research Program, who was not involved in the study, “it exists as phosphocreatine, which has a central role in maintaining adenosine triphosphate (ATP) concentrations.”

Lloyd explained that all of our cellular functions rely on constant ATP regeneration “to sustain motor proteins — e.g., muscle contraction, vesicle trafficking, ion pumping, protoplasmic streaming, and cytoskeletal rearrangement, among others.”

Its corresponding researcher, Dr. Sergej Ostojic, hypothesised that “creatine’s favourable effects in long COVID may encompass not only its role in recycling [ATP] to support metabolism in the brain and skeletal muscle, but also its anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and neuromodulatory actions.”

Lloyd expressed concern that prolonged intake of creatine could result in increased levels of cellular creatine and phosphocreatine, as the study itself found. He was concerned that the study was based on two unconfirmed assumptions:

- More creatine will improve cells’ energy supplies, including the muscles and the brain.

- There is a creatine deficit after COVID-19 or with PVFS.

“There is no evidence for creatine deficiency in post-viral fatigue states or fibromyalgia or long COVID,” cautioned Lloyd.

Ostojic said: “Earlier this year, we confirmed that long COVID patients have lower levels of creatine in the brain and muscle as compared to healthy controls. It could be possible that the brain in long COVID patients is particularly susceptible to absorbing more creatine from… circulation [to] offset the creatine deficit seen in the disease.”

While Lloyd said he found “The study is generally well-designed,” he felt it was “far too small to be meaningful.”

Ostojic does not particularly disagree, though he feels the study remains “statistically sound.” He noted that there were unfortunate limits to how many people the researchers were able to recruit due to inconvenience and high cost. Data for the study were collected from October 2021 to May 2022, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We used a relatively robust methodology that includes a non-invasive assessment of various metabolites inside the brain and skeletal muscle of long COVID patients,” Ostojic said.

Is creatine safe to use?

Ostojic expressed concern that the small size of his study imposed limits on researchers’ ability to identify possible gender-related differences in the data. He called for additional, larger studies to confirm the study’s findings and to look at creatine’s effect on long COVID patients in greater detail.

“It would be great to perhaps analyse the effects of creatine supplementation in different long COVID populations, particularly in elderly, more severe patients, those who didn’t get a COVID-19 vaccine, and patients where creatine is co-administered with other interventions, such as breathing exercises, physiotherapy, or psychological support,” said Ostojic.

“One more aspect of our study that I would like to comment on is related to the fact that long COVID patients reported no major side effects of creatine intake in our study, so we consider creatine safe when administered in this dosage for up to six months,” Ostojic said.

Lloyd raised some additional issues he had with the study, saying it employed too loose a definition of long COVID by recruiting participants with less than three months of symptoms. He also cited “no clear definition of disability and lack of rigorous exclusion of alternative medical and psychiatric conditions.”

Nonetheless, Lloyd concluded, “Looks to be safe. Needs independent replication.” Source: Medical News Today