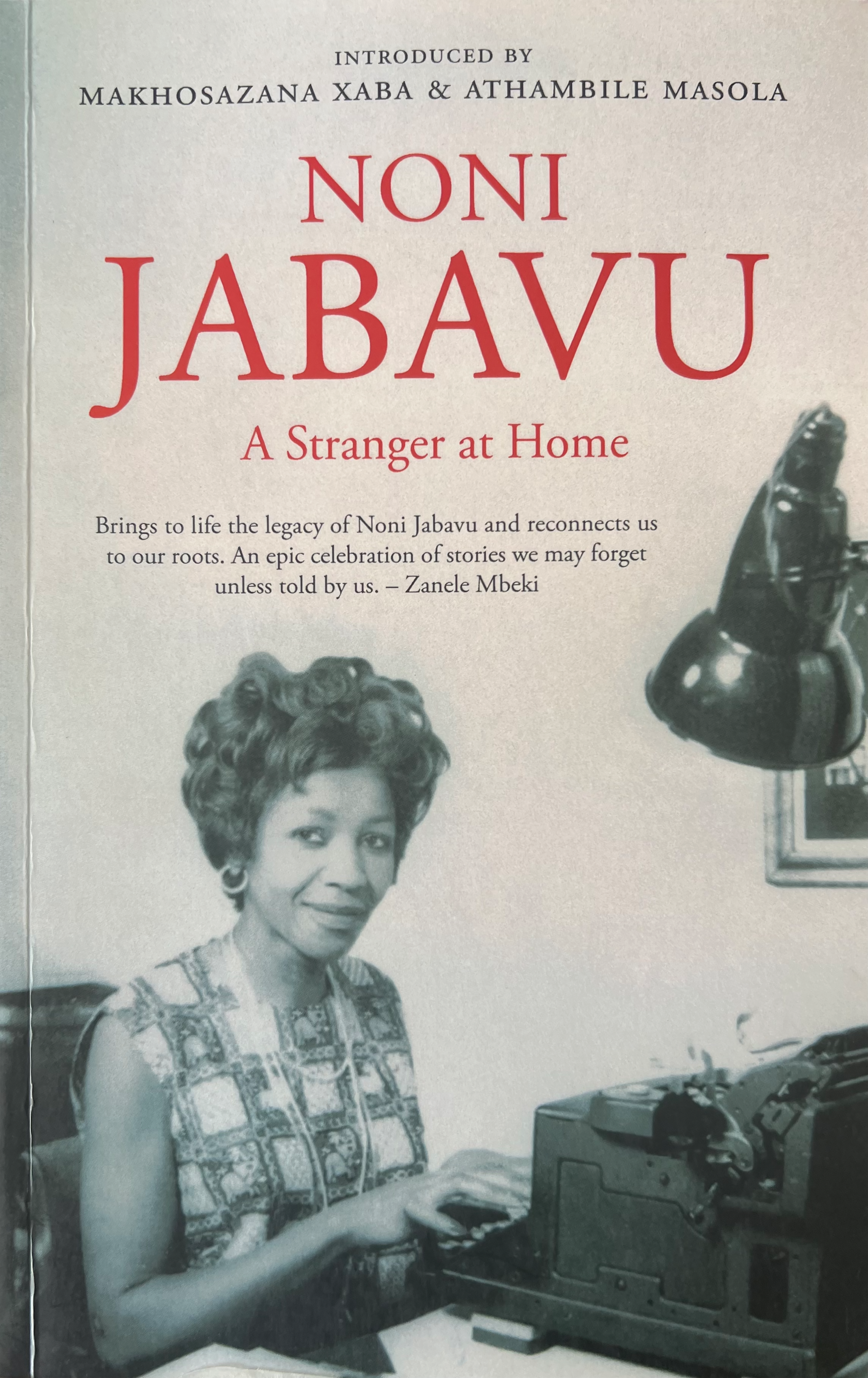

Title: Home Will Always Be Home, A Look at the Life of Noni Jabavu

By Phethagatso Motumi

Will home ever stay as we left it? Framing a year’s worth of the late author Noni Jabavu’s columns from 1977, Athambile Masola and Makhosazana Xaba help us reflect on the question…

Like too many young people, Noni Jabavu is an author who’s name and work I’m unfamiliar with, much as we are too often with writers who have paved the way for us as South African women. Reading this book felt as good place as any to rectify that narrative. As we enter an intergenerational conversation about the life on Noni Jabavu, Athambile Masola and Makhosazana Xaba probe a year worth of columns in the Daily Dispatch where Jabavu returns home in 1976/1977 to begin a biography on her father, the late DDT Jabavu – the first black professor in South Africa to teach languages at Fort Hare University.

Throughout the months, we see a woman at odds with the South Africa she grew up in and left at the tender age of 13, to the South Africa she is returning to in her late 50s, consumed with race in the thick of apartheid. Writing in what Jabavu describes as ‘personalised journalism’, we are invited into her world. As a woman who refers to herself as a black Europeans and not a South African European, her musings on her home country are very tongue-in-cheek. Her Wednesday columns give her the room to be anecdotal about the life around her and the people she’s crossed paths with whether they are friends, family or lovers.

Rubbing shoulders with everyone from jazz greats, politicians and students of Rhodes University she hosted in her hotel room, we see how her love of people shone through. What gave me pause what that her intrigue and interrogation surrounding the country’s obsession with race still resonates more than it should. In so many ways, we are reminded in the pages that there is a lot that has not changed in South Africa our land.

As someone who grew up in the 90s , in what we believed would be Mandela’s rainbow nation, I was placed alongside classmates of every colour where everyone got their turn in the sandbox. Race and racism were concepts that while learned in school, were only seen the older I got. Though we were taught about apartheid with the ideal of being fair and just, instilled from a religious standpoint; as I grew, I began to see the inequalities play out from the blatant to the microagrressive. There was a chasm that grew in me, an expectation that all should be treated equal that failed over and over again. It wasn’t only systemic issues but I experienced it in the languages we weren’t allowed to speak at break, how our hair that was policed in codes of conduct. It’s just as clear now that the racism Aunt Noni experienced in the 70s has only changed in flavour. We still have a long way to go in undoing the systemic structures put in place to put us behind in the race.

The same can be said when it comes to gender dynamics. Though women are given more opportunities to lead, it is at a slower rate than male counterparts. We are still a country trying to close the gap from how much we earn to the ways we navigate space. The quickest way for us to eradicate gender bias is through equal opportunity. We can’t be a country that is fair on paper but not in reality; more laws and legislature should change to accommodate how the roles of women have shifted through the years.

We know that you can’t be what you can’t see and that’s why there needs to be an active effort to put women in positions of power, where they can influence change. If women are graduating at higher rates, when will the workplace begin to shift? The same can be said in the literary world, where there is an imbalance of voices that are heard. We need to be actively excavating women’s literary stories and continuing on a path to shine a light on them. Uncovering all the untold stories like Stranger At Home is only a start.

Jabavu brings us into a world that explores and travels without bounds. As she shares her experiences from her holidays and lingering stay, spills tea about her family and even her many husbands, her sharp sense of humour jumps off the page. Her portrayal of the life of South Africans, of all races, and their experiences living in an apartheid stands as a reminder that the personal will always be political. She explores language and accents, our diverse use of English language as she expresses herself in Xhosa too, noting how much the nuances of the spoken word can change.

We see her become ‘acquainted with grief’, of being seen as less than just because of the colour of her skin. Her grappling with the current country in 1977 are heartfelt and decades later, present to us questions around whether we have reached the freedom that was fought for. Whether it is her wit or her candor, the more you read, the more you develop an intimacy with Auntie Noni, as if you are one of her confidants and not just one of her dear readers.

Today, Jabavu’s work provides a framework that allows her to be as a black woman. We see the 70s through her lens, without her ever having to perform the ideal of how a woman should be. Her unapologetic nature is something we should all aspire to – reminding us to take up space in every country, be the kind of women who aren’t afraid to leave an impression. May we continue to share stories with one another honestly, remind ourselves, our elders or the children that will shape the future that it’s okay to shift your perspective from time to time. In doing so, we should ask ourselves, when we think of home, whether we want it to stay exactly how we left it – whether it’s home that changes or us.

- Phethagatso Motumi is a writer across editorial and advertising whose passion is shining a light on women’s stories, a co-host for The Black Sterring podcast that interrogates series from the lens of the black women in them, as well as a content creator in her own rite.

A PACT WITH DEVIL – IN THE NAME OF “LOVE”

SYNDROME: A true-story of the horror experience of a young girl groomed to be sex slave to her paedophile captor for 16 years…

By Amanda Ngudle

The subject matter of this book is one that many will find disturbing. It’s a case of Stockholm Syndrome. Two Brit students in their final high school year visit a Greek island for seven weeks in the sun as their preparation for the imminent final exams. Once there, they find paradise on earth especially after they meet other girls their age. Without the supervision of adults, they are their own masters and drink and smoke as they please. To add sugar to a sweet deal already, they are able to work in the bars and restaurants and use their proceeds for more booze and fun. The only adult figure in their lives is one Alister who gives them employment and seeks their occasional company up at the big mansion owned by a lecherous and enigmatic boss. These visits are purported to be of innocent ornamental nature at first before things go awry. Before they do, Rachel, a 17-year-old has been groomed to think she is in a relationship with this Alister character. So engrossed in it she is left behind to pursue the relationship over her final year exams, when others go back home.

The subject matter of this book is one that many will find disturbing. It’s a case of Stockholm Syndrome. Two Brit students in their final high school year visit a Greek island for seven weeks in the sun as their preparation for the imminent final exams. Once there, they find paradise on earth especially after they meet other girls their age. Without the supervision of adults, they are their own masters and drink and smoke as they please. To add sugar to a sweet deal already, they are able to work in the bars and restaurants and use their proceeds for more booze and fun. The only adult figure in their lives is one Alister who gives them employment and seeks their occasional company up at the big mansion owned by a lecherous and enigmatic boss. These visits are purported to be of innocent ornamental nature at first before things go awry. Before they do, Rachel, a 17-year-old has been groomed to think she is in a relationship with this Alister character. So engrossed in it she is left behind to pursue the relationship over her final year exams, when others go back home.

It’s only 16 years later that the penny finally drops for Rachel, who has even ruined her marriage, pining for a paedophile, thinking he was the love of her life. It’s a disturbing read because for about 85 percent of the book, Rachel waxes lyrical about that disgusting relationship before she is able to connect the dots. It’s a thorough brain exam for people who might have found themselves in relationships that fall within the statutory rape category and South Africa has many such unions. The highlight of the book for me was the girls joining forces and bringing the pervert to book. I wish there had been more on his retribution. I would have enjoyed his journey of disgrace more. I hope many, especially parents and guardians get to read this book before most ruin their lives and end up living a life of regret.

- The Girls OF Summer-Katie Bishop (Penguin Random House) R350