BROKEN PROMISES: A story of isolation, injustice – and her ultimate betrayal by government which failed to lend dignity to her memory by fluffing the building of a community centre in honour of her legacy…

By Nathan Geffen and WSAM Reporter

More than two centuries after her body was paraded before gawking European audiences, Sarah Baartman’s dignity is once again being denied — this time by the very country that promised to restore it.

Construction of the Sarah Baartman Remembrance Centre in Hankey, Eastern Cape, began in August 2014 with a budget of R164 million. The centre, intended as a permanent tribute to Baartman’s life, suffering and legacy, was meant to be completed within two years.

More than a decade later, the sprawling four-hectare site stands unfinished, abandoned and silent — a stark monument not to remembrance, but to state failure.

The project, located near the site where Baartman was laid to rest in 2002, was envisioned as a cultural and economic catalyst for the Gamtoos Valley. Plans included a museum, archives, heritage gardens, classrooms, an auditorium, retail spaces and tourism infrastructure. Government projected the creation of 1,000 jobs and a revitalised local economy for the neighbouring towns of Hankey and Patensie.

‘Nathi Mthethwa’s broken promises’

Instead, the centre has become synonymous with delays, ballooning costs, contractor disputes and broken political promises.

By August 2016, construction was already months behind schedule. Labour disputes and repeated work stoppages plagued the site. In April 2019, then Minister of Arts and Culture Nathi Mthethwa visited the project and assured residents it would be completed that year.

“This will be another Gauteng,” Mthethwa told a packed Vusumzi community hall. “We want to turn Hankey into a smart city complete with free WiFi and shops that operate for 24 hours.”

At that point, the project’s cost had escalated to R280 million — yet completion remained elusive.

Lubbe Construction (Pty) Ltd, the original contractor, was replaced in December 2017 by Transtruct Building and Civil Contractors following protests by workers and community members. Still, progress stalled.

Ministerial intervention — and more silence

On April 17 2025, Minister of Public Works and Infrastructure Dean Macpherson conducted a site visit, describing the centre as “a prime example of how the department has failed in its core function of delivering social infrastructure to communities.”

“Over a decade, three contractors have attempted to complete the centre, yet it remains wholly incomplete,” Macpherson said at the time. He vowed decisive action and pledged that the project would finally be completed.

“I have no doubt that the measures announced today will ensure the centre’s completion as soon as possible,” he said. “It is imperative that we honour Sarah Baartman’s memory with the dignity and respect she deserves.”

But when GroundUp visited the site seven months later, there was no sign of activity. The gates were locked. There were no workers, no machinery, no security guards — only encroaching weeds and unfinished concrete.

A legacy neglected

For descendants of the Khoi-San, the abandonment cuts deep.

Yolene Basson, leader of the Gonaqua House of Apollonia, expressed anguish at what the centre has become.

“As a descendant of the Khoi-San people — the very lineage from which Sarah Baartman originates — I cannot help but feel a profound sense of sorrow, disappointment and disillusionment,” she said.

“This memorial centre was meant to be a sanctuary of dignity, remembrance and restoration for a woman whose story embodies centuries of exploitation, erasure and resilience. Instead, it has become a symbol of neglect.”

She added that the resting places of both Sarah Baartman and anti-colonial resistance leader Chief David Stuurman lie within the same desolate landscape.

“When one considers that two towering pillars of our heritage occupy this neglected space, the question of government seriousness becomes unavoidable.”

Local residents share the frustration. Hankey resident Jasper Joubert said construction had stopped long ago.

“We are now in the dark about whether the centre will ever be completed or whether it will turn into another white elephant,” he said.

Official responses and unanswered questions

Kouga Municipality spokesperson Monique Basson said the municipality welcomed the “recent intervention by the new minister” and confirmed that funding had been secured for the 2025/26 financial year.

She said the centre “holds significant potential for job creation, tourism growth and broader economic development” and that the municipality would support national government efforts to complete the project.

However, concerns over governance remain unresolved. “What we need is transparent auditing and accountability for funds spent and wasted,” Basson said.

At a recent press briefing, Macpherson described the situation as “unacceptable” and blamed failures in supply chain management. He revealed that the bidder most recently awarded the contract had “unverifiable credentials and details,” prompting the department’s director-general to cancel the procurement process.

The Independent Development Trust has now been tasked with appointing a new implementing agent. The centre has also been identified as one of 30 priority national projects under a newly established Strategic and Special Delivery Unit, which is expected to submit fortnightly progress reports to the minister.

Whether this latest intervention will succeed where others failed remains to be seen.

Daughter of the soil

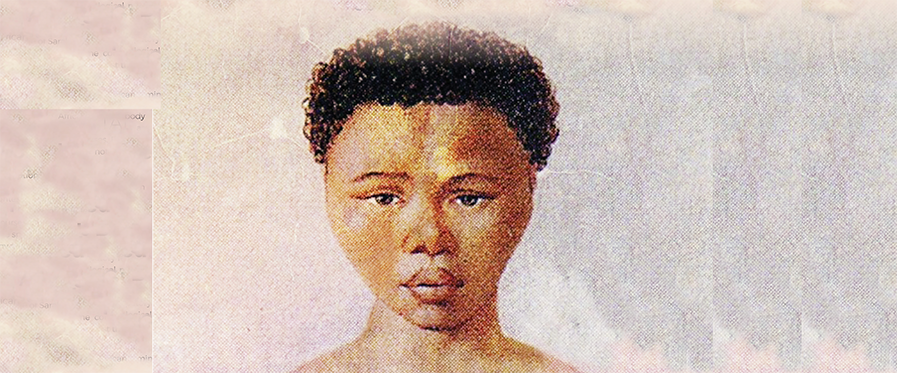

Sarah Baartman was born around 1789 in the fertile Gamtoos River Valley. Her life was irrevocably altered when her family was killed in a colonial commando raid, after which she was forced into servitude.

In 1810, under a dubious contract, she was taken to London by British ship surgeon William Dunlop and Hendrik Cesars, supposedly to work as a domestic servant. Instead, she was exhibited as a human curiosity under the degrading name “Hottentot Venus.”

Audiences in London and Paris paid to see her body, particularly her steatopygia — a natural genetic trait common among some Khoikhoi women. She was often displayed semi-naked in cage-like settings, forced to perform for public amusement.

A posthumous humiliation

Baartman died in Paris in December 1815 at around 26 years old, possibly from pneumonia or smallpox. Her exploitation did not end with her death.

French anatomist Georges Cuvier dissected her body and preserved her brain, skeleton and genitals in jars, displaying them at the Musée de l’Homme in Paris until 1974. These remains were used to advance racist pseudoscientific theories positioning African people as inferior.

A return — and another betrayal

After decades of advocacy, including a formal request by President Nelson Mandela in 1994, Baartman’s remains were finally returned to South Africa in 2002. On National Women’s Day, 9 August 2002, she was buried with dignity near her birthplace in Hankey. Her grave was later declared a national heritage site.

Yet more than 20 years later, the state’s failure to complete the Sarah Baartman Remembrance Centre represents a second stripping of her dignity — not by foreign colonisers, but by democratic South Africa itself.

Her story remains a powerful symbol of colonial brutality, the objectification of Black women, and the unfinished work of restitution. Until the centre bearing her name is completed, Sarah Baartman’s legacy will remain trapped — once again — in neglect.