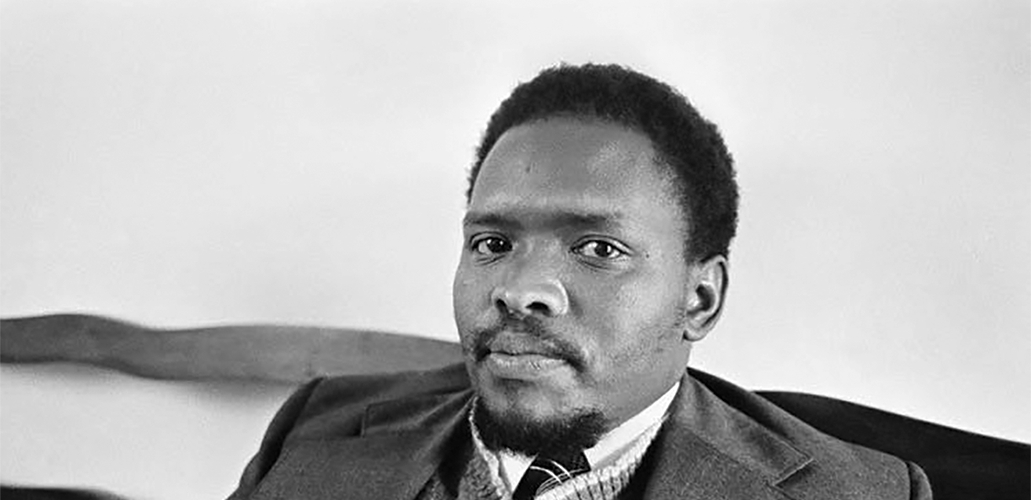

Principled leadership: Remembering the Black Consciousness Leader who radically changed the imagination of black students…

By Smangaliso Mkhatshwa

This is an ongoing posthumous tribute to Bantu Stephen Biko. When we speak about leaders who left an impressive legacy there are two mistakes we often make. We either mystify their contribution or under-report their real worth. Biko is a case in point. This is not a theoretical piece but an honest account of Biko, the human being.

Our first encounter with Biko was probably fortuitous. I had heard and read about this charismatic young student leader. His claim to fame was the founding and launch of the South African Student Organisation (SASO) in the late 1960s – a student formation that had fired the imagination of young black students in tertiary institutions around the country.

I was later to learn that the term black included all people who were discriminated against by the apartheid system on account of being non-voters or disenfranchised, including the oppressed as was the case with being an African, the so-called coloureds and Indians.

Biko passionately believed in the total liberation of South African people irrespective of race, culture or ideology.

The launch of SASO coincided with the emergence of Black theology – the project in which some of us became involved. This moment brought together black theologians and pastors who were also committed to the total liberation of South Africans by turning the traditional European theology upside down.

By sheer force of his personality and charm, Biko’s humble home in Ginsberg in the East Cape, became a hive of militant political activity. Scores of political activists who visited Biko’s humble four- roomed home shared limited accommodation facilities his home offered. The spirit of African hospitality kept everyone happy. Looking back, one wonders how the Biko family managed to feed and wine so many guests.

Lest we forget, Biko was an ordinary human being. Many women also enjoyed his company because he was so handsome and charming.

The guys were fascinated by the umhabulo or conscientisation – the adaptation of Paulo Freire’s process of helping to develop a critical consciousness to challenge injustices and create societal change – a gift for which Biko became famous for.

Biko also had a knack for merrymaking. He and Bandi, his younger sister, usually took the floor and were very good dancers.

He was also an eloquent speaker, with great capacity to charm local and international anti-apartheid friends. Almost intuitively, Biko knew he needed to delegate responsibility to others if he were to succeed in his political ventures of transforming society.

I will never forget one of my special visits to Zanempilo Community Clinic at Izinyoka, near King William’s Town, now Qonce, founded by Biko and Dr Mamphela Ramphele.

Much against my insistence that I would be happy to use whatever accommodation was available, Biko was adamant I had to be comfortable. This was an African form of hospitality.

Under a banning order in the 1970s, this did not change his humility and in all honesty, I do not remember Biko losing his temper. He was always calm, self-confident and understanding. Perfectly at ease among academics and ordinary masses.

He mobilised university students to devote their vacation periods to do voluntary community work. In the Greater Pretoria region, Biko and his colleagues organised workers, students, professional people, business leaders and the clergy, into organisations or committees for self-reliance projects.

These structures were later to play a significant role in the anti-apartheid struggle. All they asked of me as a parish priest of the Saint Charles Lwanga, Soshanguve, Tshwane, was to provide accommodation, local travel and food.

As we annually commemorate his torture and brutal murder by apartheid police while in detention on September 12, 1977, we are duty-bound to immortalise him – to make him present in our lives through good deeds of promoting social justice in our country.

We must appreciate and honour the ideals which he espoused and paid the supreme price for. Biko was intellectually endowed and articulate, but he was above all, a warm, honest, down-to-earth black leader.

His message to today’s youth can be summarised as follows: read, read, read; organise; organise, organise; work hard and play hard; implement your conviction with courage. Do not betray, let alone compromise your identity as a black South African.

If Biko were alive today, he would urge students and the youth to read voraciously and critically debate important issues of the day as well as be proud of their being black.

I have no doubt, he would have unequivocally condemned materialism, corruption and the pass-one-pass-all mindset.

He would condemn the prevalent scourge of attacks on teachers by learners, laziness at schools, sexual indiscipline as well as sacrificing the academic future of young black students.

The much-acclaimed call for decolonisation can only be seen as a logical extension of the Black Consciousness philosophy and agenda that needs to be taken seriously.

In January 1970, I was one of the five black Catholic priests who spearheaded the Black Priest Solidarity Movement. Its main objective was to radicalise the churches by practising what they preached at their churches.

We demanded de-racialisation of all institutions run by the churches and their total transformation. The launch of SASO and the birth of this movement took place more or less the same time. It was more a matter of coincidence than design. Perhaps more than anything else, it was this ideological affinity that persuaded us to find common ground.

While Biko may not have suffered fools and gossipmongers, he chided them with panache. He had the ability to motivate comrades to walk the extra mile in everything they did.

He lived up to his credo: “Work hard, pray hard and play hard”.

Supported by his key lieutenants, Prof. Nyameko Barney Pityana, Mapetla Mohapi, Mamphela Ramphela, Bishop Malusi Mpumlwana, Prof. Benny Khoapa, and a battalion of other Black Consciousness adherents, Biko ensured that the struggle for liberation was prioritised above everything else.

His banning orders did not deter him from continuing his revolutionary work.

I guess his laudable courage finally led to his assassination. While I have no evidence to back up my statement, I suspect that what precipitated his murder was his “revolutionary arrogance and defiance…” even when his tormentors wanted him to scream “Ja, my baas…”.

Even in the midst of excruciating agony, Biko said ‘’no’’ to humiliation.

It is not necessary to speculate what role Biko might have played in the post-1994 democratic South Africa. All I can confidently say is that unity of political organisations would have been on top of his agenda.

Linked to that, he would have inspired the youth, especially university students, to uphold the culture of debate, critical thinking and research. Biko would have agitated for high quality education for all South Africans and would have maintained the Black Consciousness Movement alive, as a philosophy rather than a political party.

From beyond his grave, Biko must be acutely embarrassed by a number of unsavoury things happening in the country today, some which included the demise of critical debate among students; crass materialism; rampant corruption; absence of community spirit among the youth; the desire, in behaviour and posture, to emulate colonial masters; the spurning of culture of reading and creative writing and political factionalism.

Young as he was, he was richly endowed with gravitas, charm, charisma and a values-driven ambition. His self-confidence made him feel at home among all citizens of the world – black, white, foreigners and traditional leaders.

As a human being , he had his faults and weaknesses, but the vices he did not have in abundance included arrogance, greed, selfishness, dishonesty, disrespect for others, laziness, cowardice and anti-revolutionary gossip.

My relationship with him was struggle-driven. My only regret is that I could not pay my last respects at his burial because I was in detention with scores of others in a similar position as political detainees. The news of his painful death, especially the cruel manner in which it was executed by the system, left us shattered.

Like many black SASO adherents, Biko’s sense of dress was impeccable – afro-dress being a driving force – with a penchant for selected music which promoted a great yearning for freedom message.

Regrettably, since 1994 that culture which the adherents of Black Consciousness held dear to their hearts has dissipated. Materialism has taken root, elevated to a fetish.

• Fr. Smangaliso Mkhatshwa is a Catholic priest, former education deputy minister in the Nelson Mandela cabinet and chairperson of the Moral Regeneration Movement.