CONVICTION: On January 20, 23 South Africans whose family members were murdered, forcibly disappeared or seriously injured under Apartheid have filed an unprecedented and damning application to the Constitutional Court. With the Foundation for Human Rights, they describe how the country’s political leaders made sure that the prosecutions recommended by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission would be buried, leaving a stain on post-Mandela South Africa.

By Thierry Cruvellier

“Let us start off by reiterating that there shall be no general amnesty. Any such approach, whether applied to specific categories of people or regions of the country, would fly in the face of the TRC [Truth and Reconciliation Commission] process and subtract from the principle of accountability which is vital not only in dealing with the past, but also in the creation of a new ethos within our society. (…) Government is of the firm conviction that we cannot resolve this matter by setting up yet another amnesty process, which in effect would mean suspending constitutional rights of those who were at the receiving end of gross human right violations.”

These were the words of South Africa’s President Thabo Mbeki on 15 April 1 2003 when he presented the sixth and final volume of the TRC, released a month earlier, to the parliament and the nation. However, within a few weeks of the speech, attempts by the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) to commence investigations into cases that the TRC had recommended for prosecutions were blocked. They were refused support by both the Directorate of Special Operations, a specialised unit within NPA established by Mbeki, and the South African Police Service (SAPS).

Part of the set-up of the TRC was that perpetrators of politically motivated crimes who made full disclosure were eligible for amnesty for those crimes. But perpetrators who were refused amnesty, or who chose not to apply for amnesty, were meant to face criminal prosecution.

According to the TRC final report, of the 7 112 persons who applied for amnesty, some 5 034 were rejected for not meeting the basic requirements, while the others were referred to the Amnesty Committee of the TRC, that followed the completion of the truth-telling and reconciliation process (1996-98).

Some 849 of these applicants only were granted amnesty. Murders comprised the biggest category of the crimes for which amnesty was refused. The TRC handed over a list of several hundred cases to the NPA with the recommendation that they be investigated further for possible prosecution. In its report released on 21 March 2003, it asked for “a bold prosecution policy” in those cases not amnestied to avoid any suggestion that the truth and reconciliation process was a form of impunity.

Exactly the contrary happened.

The broken promise

This unsavoury post-TRC history is at the heart of an application to the Constitutional Court filed on 20 January 2025, by 23 South Africans and the Foundation for Human Rights who represents survivors and families, in which they describe how the country’s political leaders have made sure that prosecutions would never take place.

“It is an undeniable fact that there have been virtually no investigations or prosecutions of the TRC cases since the TRC process concluded,” they say. And there is “substantial evidence” that the reason behind this failure is “a deliberate policy decision by the government to suppress them”.

The plaintiffs stress that for years they’ve asked for an independent commission of inquiry into the suppression of the TRC cases. “President Ramaphosa and the former Minister of Justice, Ronald Lamola, have ignored our requests,” they state. And they now want the highest court in the country to declare that the conduct of South African authorities was unlawful.

They remind that it was on the promise of such post-TRC prosecutions that “most victims accepted the necessary and harsh compromises that had to be made to cross the historic bridge from apartheid to democracy”.

It is this promise, they say, that has been betrayed. “This part of South Africa’s historic pledge with victims has not been kept.” Instead, “in the aftermath of the TRC, the state chose to abandon its obligations by blocking the TRC cases.” As a result, “virtually none of these cases have been pursued”.

A political betrayal

Acquittals, opportunistic guilty pleas accompanied by suspended sentences, bungled prosecutions, constant obstruction from national security and intelligence agencies, political interference at the highest level: the dense 259-page brief filed by the plaintiffs provides the most detailed and damning account of a political betrayal that has started after Mandela’s presidency in 1999.

A policy that did not apply only to crimes committed by the Apartheid regime but also by the African National Congress (ANC) or the Inkatha Freedom Party, another important anti-apartheid movement.

In early 1999, after the TRC had finalised the first five volumes of its final report, a working group called the Human Rights Investigative Unit (HRIU) was established within the NPA. It was mandated to review, investigate and prosecute TRC cases in which perpetrators had been denied amnesty or had not applied for it. The TRC then began to refer cases for potential prosecution to the NPA. The HRIU continued operations until 2000 but it didn’t proceed with any prosecutions. Another unit operated until 2003, but like the HRIU, it initiated no prosecutions.

Then came the Priority Crimes Litigation Unit (PCLU) whose mandate included to deal with the TRC cases. The PCLU launched an audit of all available cases and registered some 459 cases that were handed over from the TRC. Approximately 150 cases were identified for immediate investigation. Sixteen cases were prioritised, of which three were prepared almost immediately for indictment.

Political interference

That’s when political interference went full-scale. According to the brief, one case after another reveals the abandonment of the ambition for justice formulated in 1994 with the advent of Mandela. Like the “PEBCO 3” case, among many others:

“In 2004, former SB [Security Branch of the Police] officers Gideon Nieuwoudt, Johannes Martin van Zyl, and Johannes Koole were charged with the 1985 kidnapping and murder of three leading anti-apartheid activists, known as the PEBCO 3. This was the first and only case that the PCLU brought in respect of perpetrators who had been denied amnesty. Nieuwoudt and van Zyl applied to court to review the decisions to refuse them amnesty. The review was delayed by some five years because of the failure or refusal of the DOJ [Department of Justice] to file answering papers. Nieuwoudt died in August 2005. In 2009 the High Court ruled that an Amnesty Committee be convened to rehear the application of Van Zyl. Charges were then provisionally withdrawn against Van Zyl and Koole. Inexplicably, the DOJ never convened an Amnesty Committee and the NPA never reinstated the cases against Van Zyl and Koole, who have both since died.”

“It is highly unlikely that their decisions were spontaneous or mere coincidences,” says the brief. “It is apparent that by May 2003 both the SAPS and the NPA were reluctant to take on the TRC cases, and in all probability had been told not to do so from a political level.” The brief doesn’t shy from pointing to the highest level: “It appeared that only the head of state could make that decision, regardless of what the law and Constitution said about investigative authority.”

“The very basis of the TRC” undermined

In February 2004 an “Amnesty Task Team” (ATT) was established. According to the brief, “the ATT Report noted that a further amnesty would face challenges because of constitutional issues but nonetheless the team still had to find ways to accommodate those perpetrators who did not take part in the TRC process.

Some members argued against another amnesty, pointing out it would undermine the TRC process, while others supported a new amnesty to encourage more disclosures.” And the team decided that a new amnesty similar to that of the TRC process should be offered – “to guarantee maximum impunity for apartheid-era perpetrators,” the brief argues.

The prosecution process in relation to the TRC cases now “was to be under the thumb of political overlords”. All actors were called to “take into account national interest”, which meant, say the plaintiffs, “the shielding of perpetrators of serious crimes from scrutiny and justice”.

In an article published in March 2004, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, the iconic chairman of the TRC, reminded that those who did not receive amnesty should face prosecution and any new initiative to stop it “would be seen as negating the amnesty process of the TRC,” the brief reports. In a further statement Tutu made in a legal case later on, he talked about “a betrayal of all those who participated in good faith in the TRC process. It completely undermined the very basis of the South African TRC.”

An order “from the very top”

It had no effect. “Between 2003 and 2004 an effective moratorium was placed on the investigation and prosecution of the TRC cases. When complainants such as Thembi Nkadimeng, sister of the late Nokuthula Simelane,” a 23-year-old member of the ANC who was abducted, tortured and forcibly disappeared by the Security Branch (SB) of the Police in 1983, “approached the PCLU they were told by prosecutors that their hands were tied as they were waiting for a new policy to deal with the so-called political cases.”

“It is not known who authorised the halting of investigations,” says the brief, “but since it involved suspending work on a large number of serious crimes, mostly involving murder, it is highly likely that the authority must have come from the very top. In addition, the heads of the NPA, DSO [the Directorate of Special Operations, a specialized unit created by President Mbeki within the NPA] and SAPS must all have acquiesced in this decision, together with the cabinet ministers overseeing those departments”.

The views of the victims and their families were not sought. “Those most impacted by this massive suspension of the rule of law were not notified in advance or given an opportunity to make representations. They were kept in the dark, and only learned of it after the fact, when they pressed the PCLU for answers.”

“In effect, hundreds of murder cases were placed on ice indefinitely on the strength of unwritten arrangements.” The moratorium remained in place for between two and three years. And when the new policy was finally issued, “the clampdown only tightened”.

The resistant prosecutors

Two key persons in the NPA, Vusi Pikoli, National Director of Public Prosecutions and Anton Ackermann, head of PCLU, did not agree with the policy. They tried to resist “the charade,” explains the brief. They chose to push the Chikane case. And that case would seal their fate.

Ackermann decided to prosecute three former SB members for their role in the 1989 poisoning of Reverend Frank Chikane, the former head of the South African Council of Churches. All the evidence implicating them had already been led in the 1997 prosecution of Colonel Wouter Basson, the former head of South Africa’s secret chemical and biological warfare programme from 1982 to 1992. Basson had been acquitted in April 2002 by the Pretoria High Court but no further investigations were deemed necessary for the three former policemen, Major-General Christoffel Smith, Colonels Gert Otto and Johannes ‘Manie’ van Staden, also involved in the case. And none had applied for amnesty for this crime.

According to Ackermann, on the morning of 11 November 2004, the police were on the verge of effecting the arrests of the three suspects. On the same morning he received a phone call from Jan Wagener, the attorney for the suspects. Wagener told Ackermann that he would receive a phone call from a senior official in the Ministry of Justice, and that he would be told that the case against his clients must be placed on hold. Shortly thereafter Ackermann did receive a phone call from an official in the Ministry of Justice. The Chikane matter should be placed on hold, he was told. According to the brief, Wagener even claimed that authorization to suspend the arrests came from President Mbeki himself, “in an extraordinarily swift move”.

No TRC case proceeded between November 2004 and August 2007.

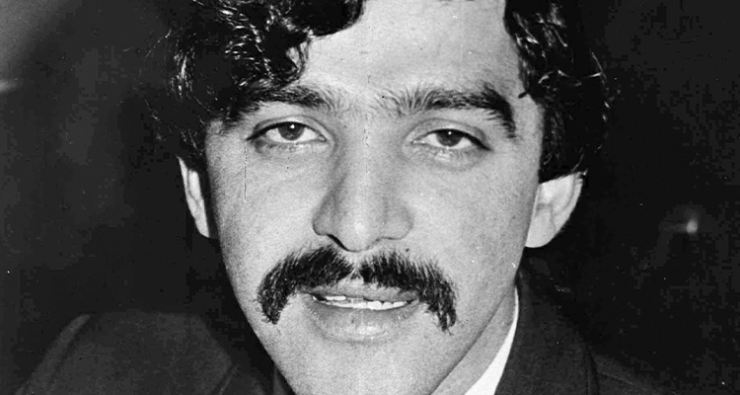

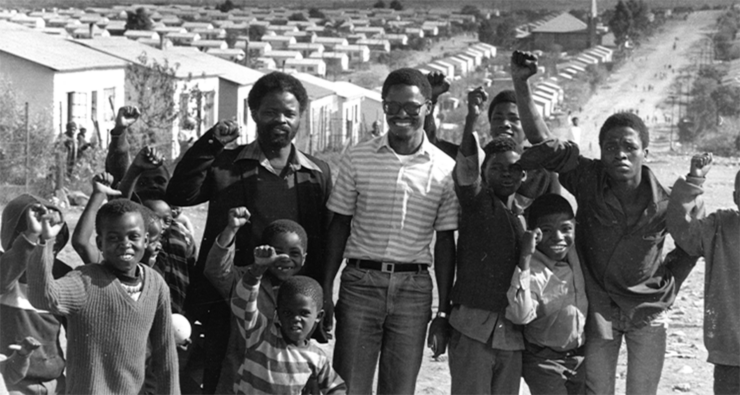

Frank Chikane arrives at the Pretoria High Court on August 17, 2007 to attend the trial of South Africa’s apartheid police minister, Adriaan Vlok, his former chief, Johann van der Merwe, and three other former security officials.

A case against Thabo Mbeki?

Long-awaited amendments to prosecution policy came in 2006. But they “not only provided for a rerun of the TRC’s amnesty criteria behind closed doors but also opened the door to practically any excuse not to prosecute,” the brief argues. The new policy did not bring an end to the moratorium. Instead, “the clampdown continued, with renewed vigour.” No investigators were attached to the TRC cases. Ackermann’s “requests to the SAPS and the DSO for competent and experienced investigators had fallen on deaf ears,” the brief says.

Worse, it was planned by the SAPS to reappoint Senior Superintendent Karel Johannes ‘Suiker’ Britz to investigate the dockets in possession of SAPS.

Britz was a former member of the Security Branch of the Police. According to Ackermann, he had regular contacts with former Police Commissioner General van der Merwe who had formed an organisation called “The Foundation for Equality before the Law”, which was intended to ensure that no further prosecutions of SB members would take place.

“Britz tried to persuade me and my deputy on numerous occasions that there was a provable case of terrorism against President Mbeki arising from the landmine campaign,” wrote Ackermann. In short, if SB members were prosecuted, a secret file against Mbeki would come out.

Britz was eventually relocated to a different unit. But it was the Chikane case that would be “the tipping point which saw the complete unravelling of the attempts by the NPA to hold apartheid-era perpetrators accountable for their crimes,” the brief adds.

Former Apartheid generals still powerful

In late 2006, Pikoli, the National Director of Public Prosecutions, was summoned to a meeting which was convened at the home of the Minister of Social Development. It was attended by the Minister of Police, the Minister of Defence, and the acting Minister of Justice.

“At this meeting it became clear that there was a fear that cases like the Chikane matter would open the door to prosecutions of ANC members,” said the brief. Pikoli wrote that “powerful elements within government structures were determined to impose their will on my prosecutorial decisions.”

On 5 January 2007, Justice Minister Brigitte Mabandla disclosed in a press statement the need for the development of a policy on presidential pardons for prisoners who alleged that their offences were politically motivated. Around this time, the Apartheid’s former Minister of Police, Adriaan Vlok, and the former Commissioner of Police, General Johann van der Merwe, both submitted statements to Pikoli. They both admitted to authorising the murder of Chikane and requested Pikoli not to prosecute them in the light of this disclosure.

Pikoli declined to grant them immunity from prosecution.

On 3 May 2007, Pikoli and Ackermann appeared before the Justice Portfolio Committee in Parliament. Pikoli warned that “whenever there was an attempt to charge members of the former Police Services there was political intervention, and effectively the NPA was being held to ransom by the former generals”.

In his view, explains the brief, “former apartheid generals seemed to be able to exert extraordinary influence over the justice system; and were able to engineer political interventions when their people were being pursued”.

“Gloves are off”

However, despite the fact that such warning came from South Africa’s chief prosecutor, no inquiry was initiated by the Parliament.

In July 2007, after several months of negotiation between the PCLU and the attorneys of the accused in the Chikane case, a plea agreement was reached. Pikoli said he would have preferred a full prosecution because Vlok and van der Merwe had confined their disclosure to facts that were largely in the public domain and declined to reveal information about the compiling of the hit lists and who was behind their compilation.

But Pikoli stated that “it was clear to me that the government, and in particular the then Minister of Justice, did not want the NPA to prosecute those implicated in the Chikane case. Therefore, a plea and sentence bargain was in my view the most appropriate compromise in the circumstances.”

On July 10 2007, Pikoli sent a memorandum to the Minister of Justice informing her of the fact that the Chikane case would be heard in court on August 17 2007 and that all the accused would plead guilty of attempting to murder Chikane by means of poisoning. According to Ackermann, this case ought to have opened the door to the prosecution of General Basie Smit, who succeeded van der Merwe as Commander of the Security Branch in October 1988, as well as other senior officers of both the Police forces and armed forces. That would not happen.

Shortly after the Chikane case hearing, a newspaper article appeared in which it was claimed that the NPA was preparing to prosecute ANC leaders. It was based on a forged note, says the brief, but after its publication, Pikoli was summoned to a meeting, on August 23 2007. This meeting was attended by several cabinet ministers, including the Minister for National Intelligence Services, the Minister of Justice, and the Minister of Social Development, as well as the National Commissioner of the SAPS, Jackie Selebi.

“According to Pikoli, Selebi said to him that the ‘gloves are now off’ and that he was ‘declaring war’ on him,” the brief says.

In a letter to the Minister of Justice in August 2007, Pikoli confirmed that there was no investigation by the NPA “against the 37 ANC leaders including the President of this country, contrary to the assertions of the National Commissioner of Police”.

Pikoli concluded his letter by requesting an urgent meeting with the Minister. He also requested an opportunity to appear before the National Security Council “to give a true account of this issue”. The Minister did not respond.

On September 23 2007, Pikoli was suspended from office by President Mbeki. Shortly after he learned that Ackermann had been relieved of his duties in relation to the TRC cases.

“With Pikoli and Ackermann out of the way, government was in a position to appoint compliant officials to lead the NPA and take charge of the TRC cases,” says the brief. “No amount of lobbying and agitating by families and their representatives would move the new leadership of the NPA to act.”

The Chikane case was the last indictment issued in a TRC related case for some 10 years. Things didn’t get much better 10 years later.

Between 2017 and 2023 five apartheid-era inquests were reopened, four of which were at the instance and pressing of the families, notes the brief. “In all these cases, the families’ legal representatives had to threaten the NPA and/or the Minister of Justice with legal action in order to get the inquests reopened.”

Following the reopened inquest into the death of Ahmed Timol in 2017, which had been spearheaded by the Timol family and their representatives, former police officer Jao Rodrigues was charged with murder in 2018. Rodrigues died in September 2021 before he could stand trial. No one else has been charged in the case.

In May 2021 during an interview in an Al Jazeera documentary titled “My Father Died For This”, ANC legal adviser Krish Naidoo claimed that the “Cradock Four case”, one of the TRC cases, “simply fell through the cracks.”

“His statement was deeply insulting to our intelligence,” write the plaintiffs. “In fact, the TRC cases were deliberately suppressed following a plan or arrangement hatched at the highest levels of government and across multiple departments. This is the real explanation for the delay.

The interference stands as a deep betrayal of those who laid down their lives for freedom in South Africa.” During that period the record of reopened cases, plea agreements and trials was “dismal,” says the brief.

South Africa’s shame

The legal brief looks at other situations in the world to shame South Africa. Chile, for instance. It is recalled that between 1998 and July 2023 Chile’s Supreme Court had handed down verdicts in more than 530 cases for dictatorship-era crimes against humanity.

In Argentina, as at the end of 2021, the Office of the Prosecutor for Crimes Against Humanity had investigated 3 525 people for crimes against humanity, of whom 1 044 were convicted.

“The main reason for South Africa’s woeful performance has been the political interference that effectively suppressed the pursuit of apartheid-era crimes within a few years of the closure of the TRC.”

South Africa may not be an exception though. In Tunisia today all cases transferred by the truth commission – the Instance for Truth and Dignity – for prosecution before specialised trial chambers have been systematically blocked by the government. And in The Gambia the promises for trials following another spectacular truth commission have gone nowhere for three years.-Justiceinfo.net

Statement by former President Thabo Mbeki on allegations of NPA interference by the Executive

01 March 2024

As a general rule, I subscribe to the understanding that government functions on the basis of legal continuity. I therefore always defer to government to clarify policies and programmes adopted and implemented while I was in government.

Accordingly, it is with some reluctance that I respond to Ms Karyn Maughan’s article: “Long-awaited NPA report gives no answers on ANC govt’s alleged blocking of apartheid trials” published on News24 on February 21. However, failure to challenge some of what Ms Maughan has written would assist to perpetuate various falsehoods.

During the years I was in government, we never interfered in the work of the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA). The executive never prevented the prosecutors from pursuing the cases referred to the NPA by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

I insist on this despite a 2021 Supreme Court of Appeal judgment which found. on the strength of uncontested submissions by former National Director of Public Prosecutions (NDPP). Advocate Vusi Pikoli, that the NPA “investigations into the TRC cases were stopped as a result of an executive decision” which amounted to “interference with the NPA.”

I repeat, no such interference ever took place. If the investigations Adv Pikoli referred to were stopped, they were stopped by the NPA and not at the behest of the Government as alleged by the Advocate. There is no record of a single instance when the NPA stopped investigating and prosecuting any case on account of the so-called “executive interference” – at least not during the period 1999 – 2008.

There are some questions which the NPA must answer honestly.

Who in the executive instructed the NPA not to do its work? Will the NPA publish this ‘instruction’ which, presumably, will be in its archives? Why did the NPA accept and respect what would have patently been an illegal instruction?

Instead of propagating falsehoods, the NPA must investigate and prosecute the cases referred to it by the TRC.

I also recall that the same Pikoli who allegedly buckled under pressure of “executive interference” concerning the TRC cases, earned a lot of respect by portraying himself as an independent and principled NDPP who defied an “all too powerful” President Mbeki, who was supposedly hell-bent on stopping him from investigating and arresting the late former National Commissioner of Police, Jackie Selebi.

The question arises, what happened to his cherished independence and commitment to principle when he acquiesced to ‘members of the executive’ on the TRC cases?

In her article Ms Maughan also refers to so-called “back door amnesties”.

What happened in this regard is that years after the dissolution of the TRC, some prisoners approached the Government arguing that they had been imprisoned for political activities – and were therefore political prisoners – but had not had the opportunity to apply for amnesty with the TRC.

The Government thought that rather than ignore these approaches, it should institute a process akin to what was pursued by the TRC Amnesty Committee to allow these prisoners to make presentations. After studying the submissions and using his Constitutional powers, the President would decide whether to grant amnesty to any of the prisoners.

Ultimately, this did not happen because the courts ruled that the intervention would violate the TRC Act. But there was nothing “back door” about the process. I addressed a joint sitting of the Houses of Parliament on this matter on November 21, 2007.

Conveniently, some people forget that the ANC was the principal architect of the Constitution of the Republic. During the years when I served as Deputy President and President of the Republic, I, together with my colleagues in Government. always bore this in mind and acted knowing that the Constitutional prescripts we helped to negotiate were binding on us.

There was never any Minister of Justice during those years who was ever authorised to instruct any NDPP to act in one way or another. No NDPP, including Pikoli, ever approached me to complain that he/she had been instructed by a Minister, or any other official. to violate the independence of the NPA as prescribed by the Constitution.

The NPA must demonstrate enough integrity by apologising for not processing the TRC cases, rather than engage in dishonourable behaviour of trying to hide behind a fig leaf which is nothing more than pure fabrication.

• Issued by the Office of former President Thabo Mbeki Johannesburg